Lawsuit demands California High-Speed Rail comply with voter intentions

Young people calling San Francisco “home” in the fall of 2008 tried to leave an enduring legacy for future generations. Enough of them signed a petition to qualify a November 2008 ballot measure that would have snidely named a new city sewage treatment plant after President George W. Bush. (The measure failed.) Much more costly and damaging was the legacy left by the 78% of San Francisco voters who approved Proposition 1A in the same election.

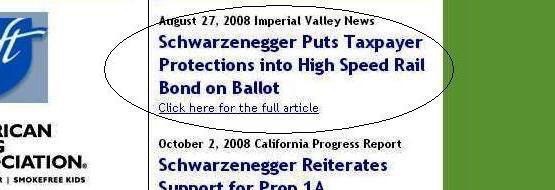

This California statewide ballot measure authorized the state to issue $9.95 billion in general obligation bonds to fund California High-Speed Rail and “connectivity” transit projects. Statewide, 52.7% of California voters approved Proposition 1A. It likely passed only because Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger and others touted taxpayer protections incorporated into the ballot measure.

More than eight years later, most voters don’t remember the details of Proposition 1A. But a coalition of California local governments and property owners is reminding the state of the protections that measure contained. They have sued the state to prevent Governor Brown and the Democratic supermajority in the California legislature from circumventing those taxpayer protections.

An amended lawsuit filed on May 25, 2017 in Sacramento County Superior Court argues that in 2016 the California legislature passed and Governor Brown signed Assembly Bill 1889, which modified the language enacted in Proposition 1A by voters. The lawsuit contends that Assembly Bill 1889 violates Article XVI, Section 1 of the California Constitution because the legislature changed a section of law enacted by voters without seeking voter approval. It calls the planned expenditures “illegal, improper, wasteful, and unconstitutional.”

AB 1889 supposedly ensures greater clarity for the California Director of Finance to determine that borrowed money from the sale of Proposition 1A bonds would make a segment of the California High-Speed Rail “suitable and ready for high-speed train operation.” But in reality, AB 1889 allows that money to be spent even if there is no chance of the segment being used for high-speed rail anytime soon, if ever.

Why would Governor Brown and a legislative majority want to enact a bill like this? Unbeknownst to most Californians, the plan for California High-Speed Rail as presented to voters in 2008 is not the plan now advancing in 2017. AB 1889 gives the State of California more flexibility to spend borrowed money on projects that may never become part of the high-speed rail system but would promote other public transit objectives.

The problems began for the California High-Speed Rail Authority in 2011, when it produced a Business Plan mandated by Proposition 1A that estimated a $98 billion cost for constructing the high-speed rail just between San Francisco and Los Angeles. Voters had been told in 2008 when considering Proposition 1A that the entire system of dedicated high-speed rail track, including segments to San Diego and Sacramento, would cost $45 billion.

To bring the cost down from $98 billion to $68 billion (now claimed at $64 billion), the Authority created a new Business Plan. It had the high-speed rail trains using Caltrain commuter track between San Francisco and San Jose as well as Metrolink commuter rail track between Palmdale and Los Angeles. This is called the “blended” plan and the shared segments are called “bookends.” But by sharing these commuter rail segments, high-speed trains would have their travel speed hindered at both ends of the route and thus could not complete the San Francisco to Los Angeles route in two hours, forty minutes as mandated in Proposition 1A.

Meanwhile, the state needed to start spending money. In 2012, the California legislature passed and Governor Brown signed Senate Bill 1029, which disbursed more than $8 billion in state and federal funds on high-speed rail construction as well as regional and local “bookends” and “connectivity” projects. For example, some of this money was appropriated for electrification and improvements of Caltrain tracks from San Francisco to San Jose. Allegedly this spending qualifies under Assembly Bill 1889 as helping to create a “usable segment” for California High-Speed Rail.

However, work on the bookends is clearly different from the viaduct construction, building demolition, and excavation work on the 29-mile stretch of civil engineering now occurring between Madera and Fresno in the Central Valley. A contract may eventually be awarded to lay track for a longer Initial Construction Segment between between Madera and Shafter (just north of Bakersfield). But for now, a high-speed rail line between San Francisco and Los Angeles is just a twinkle in the eye of Governor Brown. It is dangled as a vision just around the corner to Californians who are unfamiliar with Proposition 1A or remember little about it.

Are improvements to Caltrain commuter rail really what 52.7% of California voters were expecting in 2008 when they approved the “Safe, Reliable High-Speed Passenger Train Bond Act for the 21st Century?” And does Proposition 1A even allow money to be spent this way? Are land purchases, equipment purchases, and construction projects far away from the stretch between Madera and Shafter realistically creating usable segments for California High-Speed Rail as required by law?

Obviously, the California High-Speed Rail Authority has a strategy to spread borrowed money around while it is authorized to do so. This keeps some legislators and local elected officials happy and less willing to criticize the agency. And if a high-speed rail system isn’t going to be built in the end, why pass on the opportunity to use borrowed money authorized by Proposition 1A and spend it on commuter rail improvements that people want and need?

The plaintiffs in this lawsuit think the law takes precedence over such rationales or the compulsion to spend money if it’s available. In fact, plaintiffs make the case that Governor Schwarzenegger and state legislators saw the risk in 2008 of Proposition 1A funds being spent on projects that would not contribute to a usable segment of California High-Speed Rail. That’s why the requirement was inserted in Proposition 1A in the first place.

In a press release issued when Proposition 1A was put on the ballot, Governor Schwarzenegger declared the following: “Californians deserve the opportunity to vote on a high speed rail proposition that includes taxpayer protections and financial guidelines. With these technical changes, voters can now be assured that if the bond is approved, high speed rail would be built as planned and with fiscal controls ensuring financial accountability.”

Its details forgotten, Proposition 1A has become a license to spend borrowed money on various mass transit projects under the guise of building a $64 billion high-speed rail system between San Francisco and Los Angeles that shares track with commuter rail. The judicial branch of California government needs to bring accountability to the legislative and executive branches. This lawsuit may be the tool that finally reins in the excesses of California High-Speed Rail and its chief advocates.

Kevin Dayton, a frequent contributor to CPC’s Prosperity Digest, is the President & CEO of Labor Issues Solutions, LLC, and is the author of frequent postings about generally unreported California state and local policy issues at www.laborissuessolutions.com. Follow him on Twitter at @DaytonPubPolicy.