California Cities in Critical Condition

The specter of California’s cities and counties becoming insolvent is nothing new. Three major California cities have already declared bankruptcy, Vallejo in 2008, Stockton and San Bernardino in 2012. In October 2019, the California State Auditor’s Office reported on the fiscal health of 471 California cities.

On what the California State Auditor’s office describes as a “Local Government High Risk Dashboard,” they identified 18 high risk communities: Compton, Atwater, Blythe, Lindsay, Calexico, San Fernando, El Cerrito, San Gabriel, Maywood, Monrovia, Vernon, Richmond, Oakland, Ione, Del Rey Oaks, Marysville, West Covina, and La Habra.

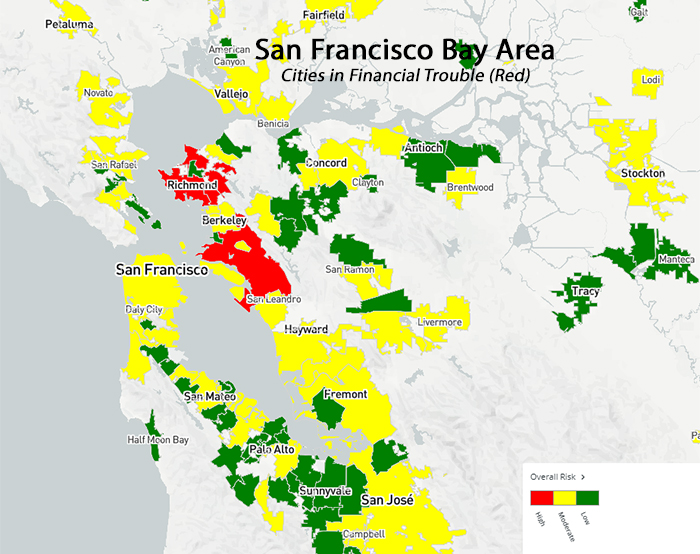

This so-called “dashboard” includes data for all the 471 cities on financial variables such as liquidity, debt, reserves, pensions and other retirement benefits. It also provides an excellent map. On this zoomed in segment, the financially troubled cities of (from north to south) Richmond and El Cerrito (contiguous), and Oakland can be seen highlighted in red.

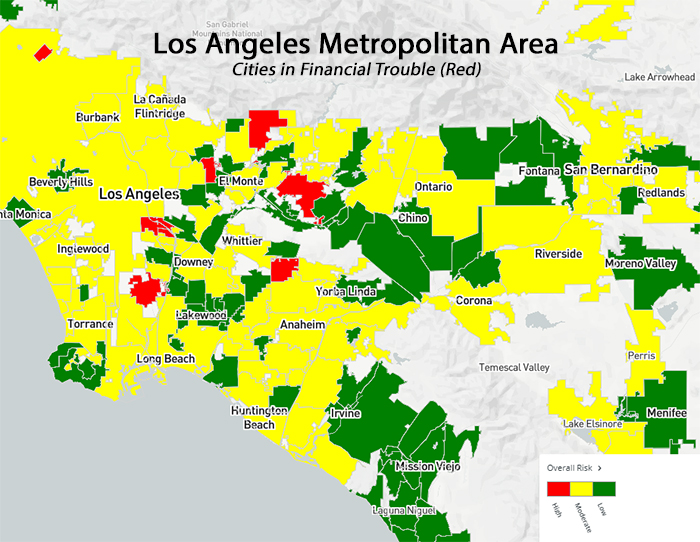

Southern California also has its share of financially troubled cities, as shown on the next map segment taken from the California State Auditor’s dashboard. Clockwise, starting from the top, the most financially endangered cities are Monrovia, West Covina, La Habra, Compton, Vernon and Commerce (contiguous), and San Gabriel.

Back in October 2019 when the California State Auditor warned Californians about 18 cities in immediate financial peril, the overall economic situation looked very different than it does today. And at that time, articles that reported on the auditor’s warning published by Reason, Governing, and Associated Press all pointed to underfunded pensions as a primary cause of their financial distress.

Not long ago, but still prior to the events of the past few weeks, during a hearing in the California State Assembly on February 26, the California State Auditor requested authorization to conduct in-depth audits of the financial health of five California cities, Blythe, El Cerrito, Lindsay, San Gabriel, and West Covina.

The one financial threat that was mentioned in all five of the California State Auditor’s requests was pensions.

“Blythe has incurred substantial debt and increasing liabilities pertaining to its city employee retirement costs, which could result in the city needing to divert more of its general fund resources to cover these costs in lieu of providing essential public services.”

“El Cerrito has not developed a long-term approach to improve its financial condition and has not addressed its increasing pension costs.”

“Lindsay anticipates its pension and other post-employment benefit costs to at least double by fiscal year 2025-26.”

“My office identified San Gabriel as the eighth most fiscally challenged city in California primarily because it has insufficient cash and financial reserves to pay its ongoing bills and it faces challenges in paying for employee retirement benefits.”

“West Covina’s unfunded pension liability is very high compared to its annual revenues, and it has only set aside a portion of the funding it will need to pay for the pension benefits already earned by its employees. Its growing pension costs will also put additional pressure on its finances.”

The Market Correction Will Affect More Than Pension Payments

It’s interesting to wonder why California’s State Auditor selected five relatively small cities for the scrutiny of a state audit. The most troubled of the five, Blythe, was number three on the auditor’s ranking by overall financial risk, behind Compton and Atwater. The City of West Covina was number 17. So why not big cities? Why not Oakland, ranked number 13, or San Jose, ranked number 23, or big Los Angeles, ranked number 32? When the denominator is 471, being ranked 32 is not good – that puts Los Angeles in the worst seven percent.

But now what? Now that the economy is slowing, and the value of investments are correcting dramatically downward?

No matter what position one may take on the financial wisdom of offering defined benefit pension plans to public employees, one point needs to be reiterated at a time like this: While it is true that an 80 percent funded status is considered adequate for a pension fund, it refers to an average across the business cycle. It does not represent what should be necessary at the end of a bull market. California’s public employee pension funds, a few weeks ago and at what we now know was the end of an 11 year bull market, were only about 70 percent funded.

This cannot be stressed enough, because it puts into proper perspective what has to be faced today. A healthy pension system at the end of over a decade of extraordinary investment returns should be overfunded. Perhaps it is credible to be sanguine about falling a bit short of the 80 percent threshold after ten years of investment doldrums, but it is absurd, and dangerous, to pretend such a level of funding is adequate after ten or more years of spectacular investment gains.

And it isn’t just pensions, anymore, that are going to affect the financial health of cities across California, from San Jose and Oakland in the north down to Los Angeles in the south. The recent and long overdue correction in the stock market was triggered by a global pandemic that is going to paralyze huge segments of the U.S. and global economy for the next several weeks, if not months. This will cause sales tax revenues to crater for as long as “social distancing” mandates remain in place, and afterwards, even an extraordinary rebound is unlikely to make up for the loss.

The impact of investment losses will impact the pension funds in two ways. Obviously they are going to have to require more from taxpayers to cover their losses, and they were already phasing in a near doubling of their required contributions – which California’s cities and counties had no idea how they were going to pay for. But the other impact, lower revenue, will pose a much bigger challenge, affecting the ability of cities and counties to pay for anything, including the pension funds.

Not only will sales tax revenue falter, but state income tax revenues will fall. California’s state government is highly dependent on income tax revenue from the wealthiest Californians. As reported by Cal Matters, “California’s tax system, which relies heavily on the wealthy for state income, is prone to boom-and-bust cycles. While it delivers big returns from the rich whenever Wall Street goes on a bull run, it forces state and local governments to cut services, raise taxes or borrow money in a downturn.”

California’s state and local governments have had over a decade to get their financial house in order. Instead, they have largely ignored the pension problem, with even Gov. Jerry Brown calling the PEPRA reforms of 2014 an inadequate compromise offering only incremental improvements. They have continued to make punitive demands on businesses, increasing taxes and spending at every opportunity. They have enacted regulations that make affordable housing and energy financially impossible for private sector interests to develop. They have emptied the prisons and opened the borders, putting additional stress on public services. They have created a state where one little push will end the good times.

That push has come.

Even the nonreligious may find an apt parable for today’s dilemma in Genesis chapter 41, verses 17 through 33. During good years, you prepare for bad years. Too bad the wisdom of the ages emphatically does not apply in woke California.

* * *

Edward Ring is a co-founder of the California Policy Center and served as its first president. This article originally appeared in the California Globe.