The annual teacher shortage canard

Despite our ever-changing world, there are some annual events we can all count on: the earth will circle the sun, Christmas will be celebrated December 25th, and the California legislature will raise taxes on its citizens. And we can now add that list – howling from the media and the teachers unions that America has a serious teacher shortage.

Most recently, Business Insider reported that “America is facing a teacher shortage.” The financial news website claims that the “U.S. is down nearly 582,000 jobs in local and state government education from February 2020.” The article helpfully explains that the shortage isn’t a new problem, but the pandemic has made it worse.

The piece quotes National Education Association president Becky Pringle, who opines, “We face a looming crisis in losing educators at a time when our students need them most. This is a serious problem with potential effects for generations.” In fact, NEA has an article on its own website replete with charts predicting near-term teacher shortages.

President Biden has jumped on the bandwagon proposing that $9 billion of the American Families Plan be set aside to address the country’s increasingly “acute (teacher) shortage — one that was worsened, though not created by, the pandemic.”

In fact, the teacher shortage fairy tale goes back quite a ways. The following statement is from the Journal of the National Education Association, published in October 1921. (H/T Antonucci.)

“Is there a teacher shortage today? There is only one answer to this question. There is still an appalling lack of trained teachers throughout the country.”

It is worth noting that over the hundred-year period, class size has been more than halved, going from 33-1 to 16-1.

Other inconvenient data for the shortage hawks comes from the late Cato Institute education policy maven Andrew Coulson, who wrote in 2015 that the nation has been on a very long teacher-hiring binge. “Since 1970, the number of teachers has grown six times faster than the number of students. Enrollment grew about 8 percent from 1970 to 2010, but the teaching workforce grew 50 percent.”

In 2017, Benjamin Scafidi released the results of a study on the “staffing surge” in public education. The researcher and Kennesaw State University economics professor found that between 1950 and 2015, the number of teachers in the U.S. increased about 2.5 times faster than the uptick in students. Even more stunning is the fact that the hiring of other education employees – administrators, teacher aides, counselors, social workers, etc. – rose more than 7 times the increase in students.

Using a narrower time frame, Mike Antonucci, director of the Education Intelligence Agency, adds that between 2008 and 2016, student enrollment was flat but the teaching force grew from 3.4 million to over 3.8 million, a rise of 12.4 percent.

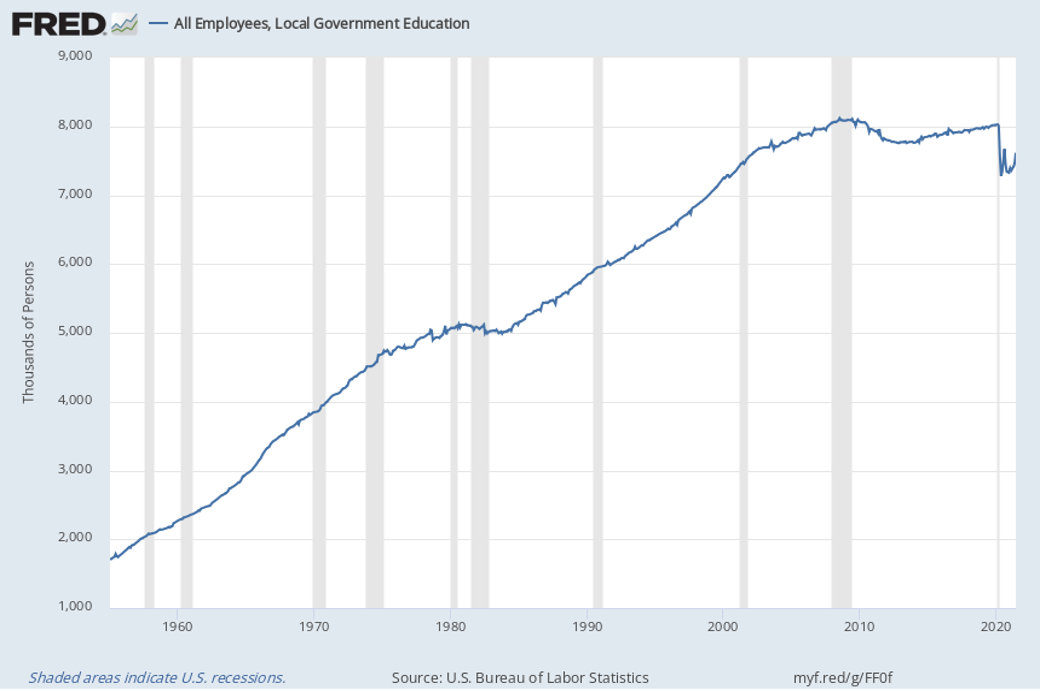

The following graph illustrates the historical growth of education workers right up to the present. Similar to the aforementioned claims, while the number of k-12 students has barely risen since the 1950s, we see a four-fold increase – despite the recent drop-off – in the number of educational employees in the U.S.

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, All Employees, Local Government Education [CES9093161101], retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/CES9093161101, August 1, 2021.

It’s important to note that the subtext behind the teacher shortage is that class size will “balloon” for the remaining teachers, and everyone knows that children learn better when classes are smaller. Right? Well, no.

As a former teacher, I know that a small class makes life easier – fewer papers to grade and parents to have to deal with, for example. That said, there is no evidence that it makes a bit of difference in student learning. In 2018, a meta-analysis – results from multiple studies – showed that small class size is a red herring. The report, produced by the Danish Centre of Applied Social Science, examined 127 studies, eliminating many that did not meet strict research requirements, and found that there may be tiny benefits to small classes for some students when it comes to reading. In math, however, it found no benefits at all and the researchers “cannot rule out the possibility that small classes may be counterproductive for some students.”

So 127 studies later, it’s basically a wash. The Danish analysis underscored Hoover Institution economist Eric Hanushek’sresults of his review of class-size studies in 1998. Examining 277 separate studies on the effect of teacher-pupil ratios and class-size averages on student achievement, he reported that 15 percent of the studies found an improvement in achievement, while 72 percent found no effect at all and 13 percent found that reducing class size had a negative effect on achievement. While Hanushek admits that in some cases, children might benefit from a small-class environment, there is no way “to describe a priori situations where reduced class size will be beneficial.”

The population bomb, Y2K, and the devils of Loudun are but a few of the hoaxes many people have embraced that eventually transitioned into history’s dustbin. Maybe one day, the teacher shortage myth will join them.