Did Ballot Harvesting Impact March 3 Bond and Tax Proposals?

Next day returns on the special election for California’s 25th congressional district indicate that a Republican, Mike Garcia, is holding a 56 percent to 44 percent lead over Democrat Christy Smith. That looks awfully good for Garcia. And while in this case Garcia’s lead does look insurmountable, in California, early returns don’t always equal final results.

According to California’s current elections code, mailed-in ballots are counted as long as they are postmarked by election day, and arrive up to three days later. In practice, this translates into final results in close elections being delayed for several weeks.

California’s election code also permits so-called “ballot harvesting,” which is alleged to swing the results of close elections. And unless, at the very least, both candidates and parties have equally effective voter harvesting operations, why wouldn’t it?

The process works this way: A campaign operative canvasses a neighborhood in the days prior to an election. Armed with a cell phone app that identifies which households have voters that are registered with the candidate’s party, they only knock on those doors.

“Hello, have you voted? No? You have not? Well do you have your ballot? Why don’t you fill it in and I’ll take it and submit it for you?” Or, if the person has already filled out their ballot, but haven’t gotten around to mailing it, “here, let me take that and get it mailed for you.”

Depending on who you ask, ballot harvesting in California was a major factor in flipping seven congressional seats from Democrat to Republican in November 2018. One thing is certain; in that election the GOP had almost no ballot harvesting operation, whereas the Democrats had thousands of paid operatives knocking on the door of every Democratic household in every battleground district.

Did Ballot Harvesting Affect the Outcome of Tax and Bond Proposals?

Plenty of controversy has been generated by the new statewide mandate to send mail-in ballots to every voter in California, along with ballot harvesting. But the focus has been on how this impacts elections to U.S. Congress or the State Legislature. Less evaluated but also impacted are votes on state and local tax and bond proposals. As part of every election, without fail, hundreds of localities put proposals in front of voters. And every election, several billion in new taxes and borrowing are at stake.

Historically, for several election cycles up to and including November 2018, California’s voters have overwhelmingly approved new local taxes and bonds. Typically over 70 percent of local tax proposals and over 90 percent of local bond proposals are approved by voters. But something happened in the primary election of March 3, 2020. Voters decided they’d had enough.

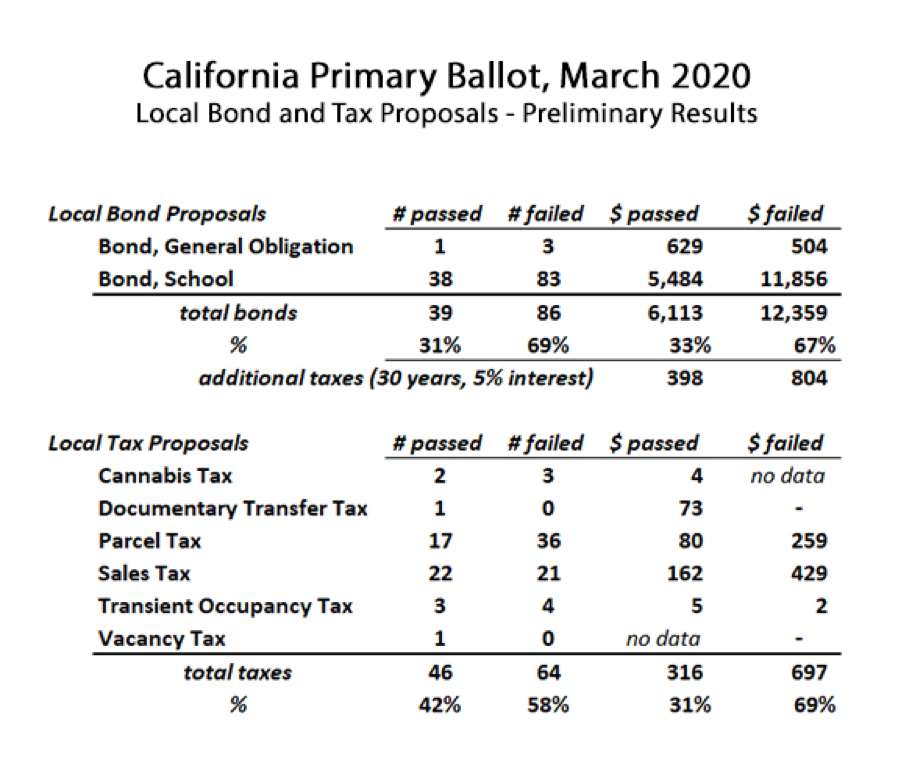

By tabulating data compiled by CalTax on local tax and bond proposals immediately after the March 3 election, the following preliminary voting results were reported:

This is a stunning result. Instead of 70 percent of local tax increases passing, only 31 percent of them were showing, so far, as approved. Instead of 90 percent of local bond proposals passing, 42 percent were showing as approved. But then what happened?

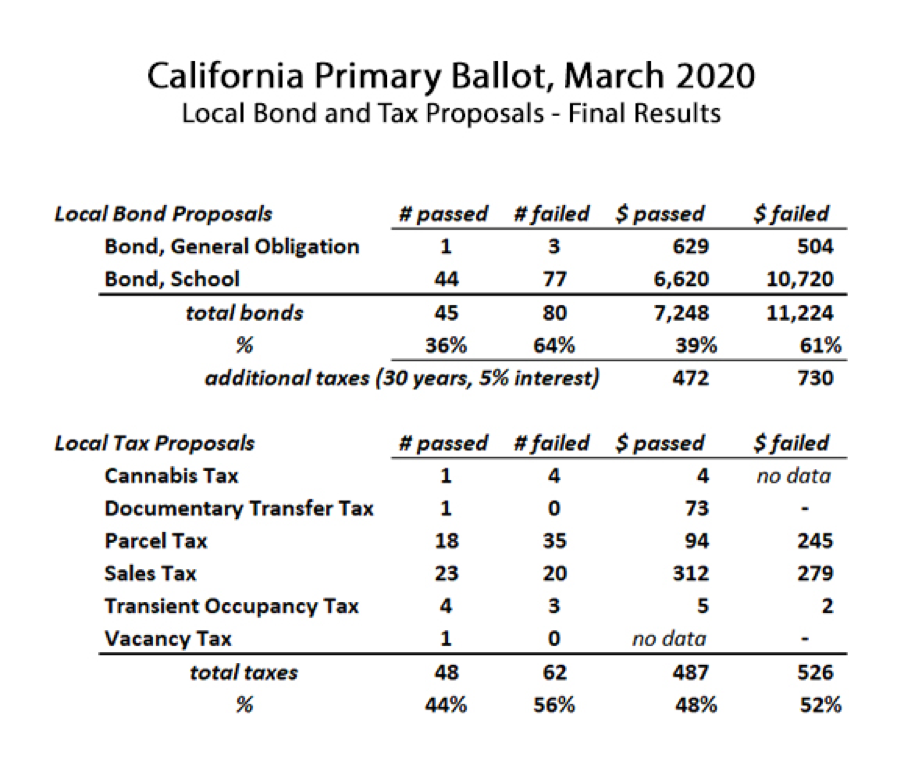

The next chart shows final results, which California’s dazzlingly efficient voting bureaucracy was able to deliver on April 21, only 49 days later. So what was the impact of late voting? How was the final outcome affected by the efforts of paid political operatives to knock on the doors of every Democrat and harvest the ballots they’d received in the mail?

As can be seen, for whatever reason, late vote counts did make a difference. The number of approved new taxes jumped from 42 percent to 44 percent. The number of approved bonds jumped from 31 percent to 36 percent. Don’t laugh. That’s another $171 million in additional annual taxes, and an additional $1.1 billion in new borrowing.

It’s worth wondering exactly how the percentages changed. For example, next day results showed 39 bonds passing, and final results showed 44 of them passing. But that’s a net number. What really happened?

The analysis performed to answer that question (an Excel file) can be downloaded here. It shows every tax and bond measure that appeared on a local ballot in California on March 3, comparing next day results to final results. In reality, eight bond measures that were losing a day after the election ended up passing, and two bond measures that were passing in the next day results ended up losing. With respect to the local tax measures, it was a bit closer: five tax measures flipped from fail to pass, and three flipped from pass to fail.

What Does It All Mean?

A New York Times journalist, Jennifer Medina, citing tracking data in California, reported that “roughly 56% of voters 65 and older returned a mail ballot. Just 19% of those younger than 35 did so.” Medina was reporting data from the May 12 special election in California, but it’s interesting to wonder if it holds true for the state at large.

Most of the analysis published in mainstream media, including the New York Times and the Washington Post, claim vote-by-mail does not help either party. Mainstream media also promotes a consensus that vote-by-mail does not increase the risk of fraud, as this typical analysis from NPR helpfully attests. But the NPR report also reinforces the argument that older voters tend to be far more likely than young voters to submit mail-in ballots.

With two elections already behind us in California in 2020, a few observations may be useful. First, voter sentiment has changed significantly. The level of support for new taxes and bonds has nearly inverted, a shift far too big to dismiss as a blip. With the pandemic shutdown having crashed public sector tax revenue, this should be a worrisome development for anyone who wants more taxes and more borrowing. Will the pandemic crisis exacerbate voter disillusion with new tax proposals, or offer them a new motivation to approve new taxes?

The other observation that might come out of these 2020 California elections is that vote-by-mail, notwithstanding possible concerns about fraud, may actually help Republicans. Voter harvesting, on the other hand, will harm Republicans. They will be harmed because it is unlikely that in California, where Democrats have far more money to spend (public-sector unions, left-wing billionaires), the GOP cannot hope to match the Democrat voter harvesting operation. And even if they do, come November, they will knock on GOP households that are far more likely to have already mailed in their ballots, whereas the Democrat households will be more likely to still be holding on to theirs.

This article originally appeared on the website California Globe.