How Much Fossil Fuel is Left?

Fossil fuel powers the economic engine of civilization. With a minor disruption in the supply of fossil fuel, crops wither and supply chains crash. With a major disruption, a humanitarian apocalypse engulfs the world. Events of the past few months have made this clear. Without energy, civilization dies, and in 2020 fossil fuel continued to provide over 80 percent of all energy consumed worldwide.

This basic fact, that maintaining a reliable supply of affordable fossil fuel is a nonnegotiable precondition for the survival of civilization, currently eludes far too many American politicians, including the president. Quoting from energy expert and two-time candidate for Governor of California Michael Shellenberger, “One month ago, the Biden administration killed a one million acre oil and gas lease sale in Alaska, and seven days ago killed new on-shore oil and gas leases in the continental U.S. In fact, at this very moment, the Biden administration is considering a total ban on new offshore oil and gas drilling.”

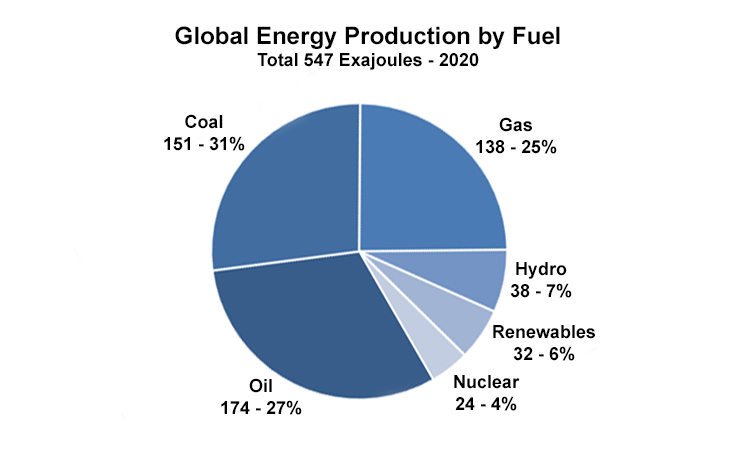

Another basic fact, easily confirmed by consulting the 2021 edition of the BP Statistical Review of Global Energy, is that if every person living on planet earth were to consume half as much energy per year as the average American currently consumes, global energy production would have to nearly double. Instead of producing 547 exajoules (the mega unit of energy currently favored by economists) per year, energy producers worldwide would have to come up with just over 1,000 exajoules. How exactly will “renewables,” currently delivering 32 exajoules per year, or 6 percent of global energy, expand by a factor of 30x to deliver 1,000 exajoules?

The short answer is it can’t. Despite the fanatical, powerful group-think that calls for abolition of not only fossil fuels, but also most hydroelectric power and all nuclear power, the reality is that most nations of the world are going to continue to develop every source of energy they can, and they’re going to do it as fast as they can. Renewables may have a growing role in that expansion, but renewables are decades away from providing more than a fraction of total global energy production.

How much fossil fuel reserves are there?

The argument against fossil fuel rests on two premises. The first is that CO2 emissions from burning fossil fuel is causing a climate emergency. Without (for now) arguing against the theory that anthropogenic CO2 is going to destroy the planet, suffice to say that we’d better adapt to whatever climate change is coming, because the only nations even semi-serious about eliminating use of fossil fuel are Western nations. Once again, recent events have demonstrated that fossil fuel isn’t going anywhere, and nations that renounce its use condemn themselves to deindustrialization and eventual irrelevance.

The other premise underlying the drive to eliminate fossil fuel is more pragmatic. We are reaching “peak oil,” and there simply isn’t enough of it to last much longer. Oil, natural gas, and coal are all nonrenewable resources, with finite reserves. This argument is worth examining in depth.

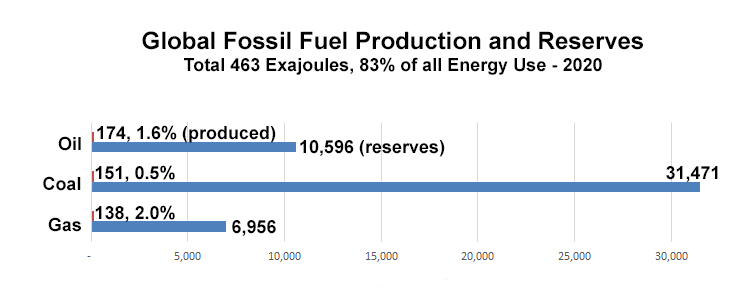

The next chart shows how much fossil fuel is left in the world in the form of proven reserves (the blue bars), as well as how much, by fuel, was used up in 2020 (red bars, which are so short you can hardly see them). As shown on the chart, in 2020 174 exajoules of oil was burned, with 10,596 exajoules remaining – a 61 year supply. Also shown on the chart, as of 2020, and at current rates of consumption, there is a 208 year supply of worldwide coal reserves, and a 50 year supply of natural gas.

These proven reserves, also reported in the 2021 edition of the BP Statistical Review of Global Energy, don’t tell the whole story. There are “unproven” reserves, which would very likely double the amount of fossil fuel energy available for extraction, and possibly much more.

To understand this, first note that predictions of “peak oil” have been consistently wrong. In a well known early example, back in 1956 economist M. King Hubbert presented a paper to the American Petroleum Institute where “he noted that the rate of consumption of these fuels was greater than the rate at which new reserves were being discovered.” Hubbert predicted U.S. oil production would peak in the 1970s, and indeed there was a peak in 1971, at just over 10 million barrels per day. By 2008, total U.S. production had fallen to as little as 4 million barrels per day. But thanks to the introduction of fracking and deregulation, by 2019 domestic oil production had risen to a new peak of over 12 million barrels per day. New technologies and new exploration resulted in a major expansion of proven reserves.

Another indication of how much energy may remain out there in unproven reserves that are waiting to be tapped is in this 2022 report by the U.S. Energy Information Administration. It estimates America’s total proven natural gas reserves at 473 trillion cubic feet, but estimates additional unproven reserves of natural gas to total another 2,867 trillion cubic feet – six times as much.

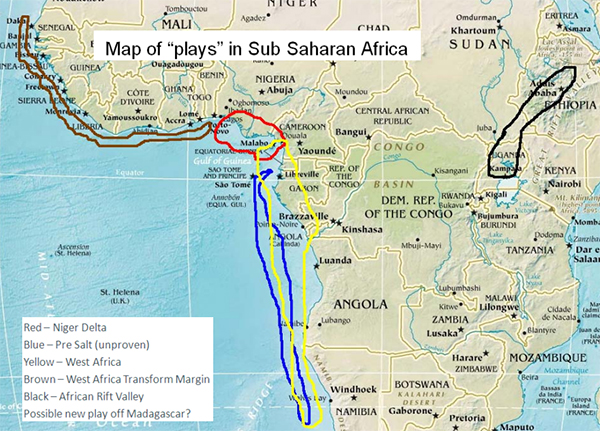

Finally, consider this map of the Sub Saharan portion of the African continent. Consider the scale of this map; this continent is over 4,600 miles across at its widest point, compared to the lower 48 of the United States at only 2,800 miles wide. As depicted on the map, promising regions for onshore and offshore oil and gas exploration amount to hundreds of thousands of square miles. Africa is a massive continent, with massive reserves of oil and gas. Now consider this report on “Natural Gas Reserves By Country.” Despite its vast potential, the first Sub Saharan nation on the list is Angola, at number 40, with proven gas reserves equal to 0.14 percent of total global reserves. That’s probably a minute fraction of what Africa’s got.

Africa isn’t the only place where fossil fuel reserves have been barely tapped. Expect deposits to be found as needed pretty much everywhere, from the polar regions to countless offshore sites on the continental shelf, and elsewhere.

The current energy crisis is going to harm nations in Africa, and in other developing regions, far more than it will harm Western nations, and that’s saying a lot, considering how cold it’s going to get in places like Berlin and Copenhagen if Russian gas is turned off this winter. But in African nations, the primary source of affordable energy is “biomass.” Put less euphemistically, and to this day, hundreds of millions of Africans still desperately strip the forests in order to gather fuel to cook food, because Western nations and Western dominated banks have prevented them from developing clean natural gas.

This humanitarian folly is multi-faceted. In 1950, there were 227 million people living in Africa. Today, there are 1.4 billion Africans, and by 2050 Africa’s population is projected to be 2.5 billion. On what had been a stable population for centuries, this population explosion was facilitated by Western aid which reduced infant mortality and, overall, provided food aid and healthcare. But now, Western nations are denying Africans the prosperity and self-sufficiency that comes with affordable energy, supposedly to avert climate disaster.

This absurdity ignores the catastrophic impact of a burgeoning population denied access to fertilizer, industrial agriculture, and a reliable power grid, because these are byproducts of fossil fuel. Deliberately denying Africans the fundamental prerequisite for prosperity means their population will continue to explode at the same time as millions of them, desperate for food and fuel, will continue to strip the forests of wood and wildlife. On the flipside, as has been proven worldwide without a single exception, when prosperity is introduced to a culture, the population stabilizes and begins to decline.

There is plenty of fossil fuel

According to the most authoritative source on energy in the world, as noted, total proven reserves of fossil fuel currently total 49,023 exajoules. This means that just with proven reserves, and if only fossil fuel were used, and if global energy consumption were doubled to 1,000 exajoules per year, there would still be a 50 year supply of energy. How much more fossil fuel can be extracted from unproven reserves is anybody’s guess, but it is a safe bet that twice as much more is available, meaning there’s at least another century worth of fossil fuel even if we used nothing else to power civilization.

The benefits of abundant cheap energy are obvious: prosperity and voluntary population stabilization. In the decades to come, other forms of energy will also be further developed. If hydroelectric power doubles, while nuclear power and renewables both go up by an order of magnitude, the three together would provide 636 exajoules of power per year. Under that scenario, fossil fuel use could remain near current levels, and total global energy production would still double to 1,000 exajoules.

What is impossible, however, is for renewables alone to achieve this level of growth. To begin with, more than half of renewable energy today comes from biofuel and biomass, which – and this is yet another irony alert – is already wreaking havoc across the tropics as hundreds of thousands square miles of rainforest are incinerated to make room for cane ethanol and palm oil plantations. And then there are the minerals required for the wind turbine towers, the silicon photovoltaics, and the billions of megawatt-hours of battery farm capacity. Where are the Malthusians when you need them?

Humanity can adapt to climate change, if there is sufficient prosperity and political will. We are already on the brink of commercializing innovations to turn carbon dioxide into liquid fuel. Should atmospheric CO2 be the horrific pollutant that so many claim it to be, it can be removed from the atmosphere and converted into fuel to drive our trucks around.

Until that time, fossil fuel isn’t going anywhere.

This article originally appeared on the website American Greatness.

***

Edward Ring is a contributing editor and senior fellow with the California Policy Center.