If you don’t give city employees a pension, what happens?

San Diegans voted five years ago this month to switch all new city hires, except police, from pensions to 401(k)-style individual investment plans, becoming one of the first big cities to take the plunge.

Jacksonville, Fla., took a bigger step last April, switching all new employees including police and firefighters to 401(k)-style plans. Last week, Pennsylvania’s governor signed legislation switching new state employees and teachers to three 401(k)-based options.

The Michigan legislature approved legislation last week that puts new teachers in a 401(k)-style plan unless they opt for a “hybrid” pension-401(k) plan. Michigan was the first to switch state employees to 401(k)-style plans two decades ago, followed later by Alaska and Oklahoma.

As one of the city forerunners of what public pension advocates hope does not become a trend, San Diego will be watched. The 401(k)-style plan is the radical reform, avoiding all pension debt for new hires, unlike milder California reforms that curb future pension costs.

Gov. Brown’s pension reform five years ago, requiring new hires to work longer to earn full pensions and making other modest changes, covers CalPERS, CalSTRS, and 20 county systems — not UC and a half dozen big cities with their own pension systems, like San Diego.

A key part of a reform approved by San Jose voters five years ago, cutting the cost of pensions earned by current workers, was blocked by a court. As the police force decreased, a plan preserving some savings was negotiated with unions and approved by voters last fall.

While the number of private-sector pensions, usually offered only by large companies, continues to drop one of the issues is whether the switch to 401(k) plans, originally designed to supplement pensions, will provide an adequate retirement.

An additional issue for local governments that switch is a job market where government pensions are standard. Remaining competitive, particularly for police, is the reason San Bernardino and Stockton did not try to cut pension debt while in banrkuptcy.

So, how’s San Diego doing five years into the switch?

Little information was readily available last week from the office of Mayor Kevin Faulconer, a signer of the ballot argument for Proposition B, or former Councilman Carl DeMaio, an author of the measure, or the San Diego City Employees Retirement System.

A union official said offering new hires a 401(k)-style plan rather than a pension is having an impact on recruitment, particularly for middle and upper management and skilled positions such as engineering and surveying.

Michael Zucchet, San Diego Municipal Employees Association general manager, said the switch reduces services by contributing to an overall vacancy rate in city positions of about 10 percent, rising to 15 to 20 percent in some positions.

He cited the example of a staffing crisis for city 911 dispatchers on emergency calls. A survey found the total compensation of San Diego dispatchers was 30 percent below the regional average, resulting last June in a 26.6 percent pay raise over three years.

Firefighter positions (represented by a different union) still attract many applicants, said Zucchet. But a high failure rate raises questions about quality, and a loss of new firefighter suggests the city is a “training grounds” for other fire departments.

For persons pursuing a career in public service, said Zucchet, pensions are offered by San Diego County, 17 cities in the county that contract with the California Public Employees Retirement System, and other government agencies throughout the region.

“Because of that, to be perfectly frank, you would have to be sort of crazy to choose the city of San Diego,” Zucchet said. “There must be reasons other than compensation and benefits to choose here, and that’s still being felt.”

One of the twists in the San Diego reform is that the city’s independent budget analyst said in the ballot pamphlet that switching to a 401(k)-style plan is not projected to save money over the next 30 years.

Savings from ending pensions for new hires, except police, would be offset by the cost of the new 401(k)-style plan that allows a maximum city contribution of 9.2 percent of pay for most employees, 11 percent for safety employees. City employees do not receive Social Security.

But the analyst projected potential Proposition B savings of $963 million over 30 years from a freeze on pay counted toward pensions until June 20, 2018. Salaries could be increased during the freeze, but the increase would not count toward pensions.

Zucchet said because the freeze on pensionable pay was “locked in four or five years ago, the pension system was able to change its projections, and there was a realized long-term savings.”

About $200 million is expected to be saved over 15 years by increased early payments of the debt for closing pension plans, a government accounting requirement said the latest actuarial report.

Proposition B was said to be needed to curb a projected $100 million increase in city pension costs during the next decade. Zucchet said costs had already been cut by steps such as an agreement in 2009 to give many employees a much lower pension.

San Diego was fertile ground for radical pension reform because two city deals that cut payments into the pension fund while increasing pension benefits resulted in soaring debt, budget cuts, a federal bond probe, lawsuits, and national notoriety.

Now the annual city payment to the pension system is scheduled to jump to $324.5 million in July, up from $261.1 million this fiscal year. The actuarial report said the increase is mainly due to a new estimate that retirees will live longer.

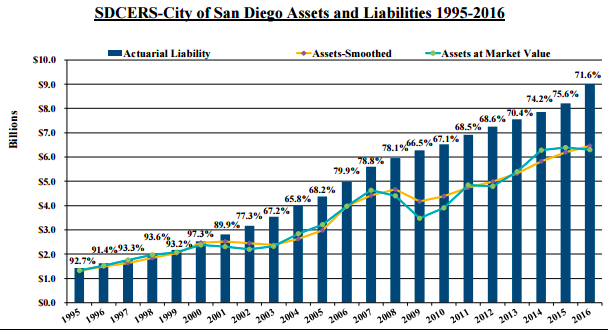

Longevity also is the primary reason the pension funding level dropped to 71.6 percent as of last June 30, down from 75.6 percent the previous year. The pension debt or unfunded liability jumped from $2 billion to $2.56 billion, largely for the same reason.

The actuarial report shows a very high weighted total city contribution rate, 88.7 percent of pay. The pension contribution exceeds pay in three plans: “police old” 114.5 percent of pay, “fire old” 122.6 percent, and “elected” 153.2 percent.

A San Diego County Taxpayers Educational Foundation report in March said the current fiscal year city pension contribution was 10.94 percent of the operating budget, amounting to $233 per capita. The foundation is planning a new study on Proposition B.

There is still a chance that Proposition B may be repealed. An appellate court overturned a state labor board ruling that Proposition B was invalid because city officials did not bargain the issue with unions.

Last month, unions asked the state Supreme Court to review the appellate ruling. If the initiative is overturned, the city may face the cost of giving retroactive pensions to more than 3,000 employees that now have a 401(k)-style plan.

Reporter Ed Mendel covered the Capitol in Sacramento for nearly three decades, most recently for the San Diego Union-Tribune. This article first appeared on his Calpensions.com on June 18, 2017.