Jamming Janus – The Public Union Empire Strikes Back

In June 2018 the U.S. Supreme Court ruled on the Janus vs AFSCME case. The result of the decision is that public employees not only have the right to refuse membership in a union, but also the right to refuse to pay so-called “agency fees” to the union.

Unions had been preparing for years for a ruling like this. The Janus case was the successor to a similar case, Friedrichs vs the CTA, which after taking years to work its way through lower courts, ended up deadlocked after the untimely death of Justice Scalia in early 2016.

To hear the reports over the years, and especially in late 2017 and the first half of 2018, Janus was going to be a catastrophe for public sector unions. On the website of a California AFSCME Council, a news article late last year was titled “Judging Janus: Will California’s Unions Survive?” When the Janus decision was announced last June, Time Magazine published an article entitled “The Supreme Court’s Union Fees Decision Could Be a Huge Blow for Democrats.”

Not so huge, actually. What actually is happening post-Janus, at least so far, might remind one of the Y2K virus. Much ado about nothing. The unions were ready.

How public sector unions prepared for Janus, especially in California, is testament to their incredible power.

In June 2018 the California Policy Center published a list of the laws pushed by public sector unions in the state legislature, all of which were designed to minimize the impact of Janus. Here is an updated list:

1 – Requires public employers to conduct a public employee orientation for new employees within four months of hire, and provide a union representative with at least 30 minutes to make a presentation – AB 2935 (2016, passed).

2 – “Would require government agencies to negotiate the details of when, where and how unions could have access to recruit new employees; and to provide job titles and contact information for all employees at least every 120 days (as reported by EdSource) – AB 119 (2017, passed).

3 – Expands the pool of public employees eligible to join unions – AB 83 (passed), SB 201 (passed), and AB 3034 (vetoed).

4 – Makes it difficult, if not impossible, for employers to discuss the pros and cons of unionization with employees – SB 285 (passed) and AB-2017 (pending).

5 – Requires the time, date and location of new public employee orientations to be held confidential – SB 866 (passed).

6 – Precludes local governments from unilaterally honoring employee requests to stop paying union dues – AB 1937 (pending) and AB-2049 (pending).

7 – Makes employers pay union legal fees if they lose in litigation but does not make unions pay employer costs if the unions lose – SB 550 (passed).

8 – Moves the venue for dispute resolution from the courts to PERB (Public Employee Relations Board), which is stacked with pro-union board members – SB 285 (passed) and AB 2886 (vetoed).

THE CONTRACT TRAP

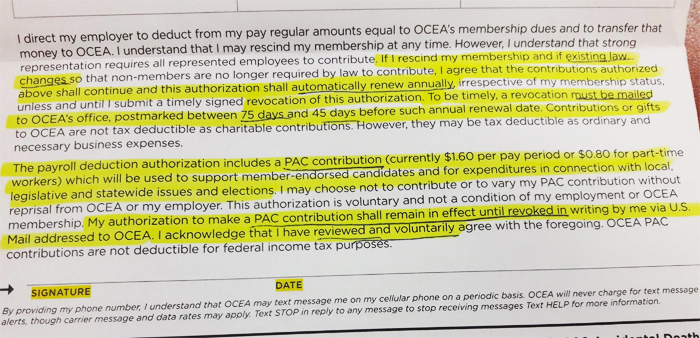

Take a look at this example of an actual recent agreement between an employee and their government union:

As can be seen, this contract has been modified to read “if I rescind my membership and if existing law changes so that non-members are no longer required by law to contribute, I agree that the contributions authorized above shall continue and this authorization shall automatically renew annually, irrespective of my membership status, unless and until I submit a timely signed revocation of this authorization. To be timely, a revocation must be mailed to OCEA’s office, postmarked between 75 and 45 days before such annual renewal date.”

This is known as “contract trapping.” Adding this type of language to contracts is one of the principal means by which public sector unions are retaining current members, and entrapping new ones. Whether or not cleverly written contract traps override the Janus ruling is the issue in a recently filed lawsuit, Few vs. UTLA.

In this case, the plaintiff, Thomas Few, is a special education teacher in Los Angeles. Few was told he could end his membership in the United Teachers of Los Angeles union. But even as a nonmember, the union told him that he would still have to pay an annual “service fee” equivalent to his union membership dues. Few’s position, which is likely to be upheld, is that he cannot be compelled to pay anything to a union he does not choose to join, regardless of what the payment is called.

UNION MEMBERSHIP POST-JANUS

Assessing union membership is an inexact science. The tax returns filed by the unions, Form 990s, are available online. But these forms don’t report the number of members, only the revenue collected, and they are usually a year or two behind.

For example, 2019 will be the first full year that unions will have been living under Janus, and those tax returns probably won’t be available online until late 2020 or later in 2021. The only other way to learn the direction of union membership trends is to rely on what the unions themselves make public, or – sometimes this is effective – to make public records act requests to the payroll departments of public agencies.

On that score, so far the unions seem to be weathering Janus just fine. Based on the public record act requests they made, the Sacramento Bee reported last month that union membership among California’s state workers (not including higher education or K-12 employees) was up about 300 since June, reporting 131,410 dues paying members in October, vs. 131,102 in June. The same report cited the California Correctional Peace Officers Association gaining more than 1,500 members between June and August 2018, and California’s Professional Engineers union gaining 340 members over the summer.

This evidence suggests union membership post-Janus is holding steady due to the new laws and contract language the unions have working in their favor. But unions continue to adapt to the inevitable loosening of the rules that have made it easy for them to collect dues and fees from public employees. Public sector union leadership understands that people either join or quit public sector unions for two reasons – economic, and ideological.

The economic argument for belonging to a union is nuanced. Clearly union “negotiations” with politicians these unions can make or break in the next election have borne fruit. In California, public employees earn pay and benefits well in excess of what private sector workers earn. On the other hand, union dues often exceed $1,000 per year, and public employees may want to keep that money, particularly if they believe the unions have wrung as much as they’re going to wring out of public budgets that are already stretched thin.

Ideological reasons to choose or reject union membership formed the premise of the Janus case; that all public sector union activity is inherently political, and constitutional freedom of speech protection means that public employees cannot be forced to support political activities they disagree with. How many public employees object enough to the political positions of their unions to quit, or never join? To minimize this, unions are pivoting towards emphasizing the services they provide, and downplaying their political activism.

It remains up to opponents of public sector unions to not only fight to enforce Janus, and help members withdraw from unions, but also to continue to educate public workers and the public at large about how much public sector unions have harmed California.

The public schools in California provide a good example. There is a growing nonpartisan consensus that unionizing public education has been a disaster. As argued in the Vergara case in 2014, union work rules in the areas of dismissal, tenure, and layoffs, have had a disastrous impact on the quality of education in California’s most vulnerable communities. Unions have been the implacable, and very effective opponents of charter schools and school vouchers, which would only help improve education. And unions have promoted left-wing classroom indoctrination, something that should even concern leftists, insofar as it takes time away from teaching fundamentals.

Another compelling example of public sector unions harming California are the status of public sector pensions. California’s pension systems, by and large, remain only around 80 percent funded, even though the stock market is at the tail end of a record breaking ten year bull run. In California, public sector pensions and other retirement benefits average over $70,000 per year for 30 years of work, many times what Social Security offers, and there isn’t enough money set aside to pay them. Payments into California’s state and local pension systems are projected to double, from roughly $30 billion per year today to nearly $60 billion per year by 2024. Government unions negotiated these unsustainable pension benefits, and consistently fight against attempts at reform.

Will public sector employees vote with their feet, and leave their unions? Post-Janus, that is easier than ever, and pending litigation will make it easier still. But it is not clear how many of them will make that choice.

* * *