Just How Much Money Might CalPERS Have to Collect in an Economic Downturn?

When evaluating the financial challenges facing California’s state and local public employee pension funds, a compelling question to consider is when, exactly when, will these funds financially collapse? That is, of course, an impossible question to answer. CalPERS, for example, manages hundreds of billions in assets, which means that long before it literally runs out of cash to pay benefits, tough adjustments will be made that will restore it to financial health.

What is alarming in the case of CalPERS and other public sector pension funds, however, is the relentless and steep rate increases they’re demanding from their participating employers. Equally alarming is the legal and political power CalPERS wields to force payment of these rate increases even after municipal bankruptcies where other long-term debt obligations are diminished if not completely washed away. Until California’s local governments have the legal means to reform pension benefits, rising pension contributions represent an immutable, potentially unmanageable financial burden on them.

SOUTH PASADENA’S PAYMENTS TO CALPERS ARE SET TO DOUBLE BY 2025

The City of South Pasadena offers a typical case study on the impact growing pension costs have on public services and local taxes. Using CalPERS own records and official projections, the City of South Pasadena paid $2.8 million to CalPERS in their fiscal year ended 6/30/2017. That was equal to 25% of the base salary payments made in that year. By 2020, the City of Pasadena is projected to pay $4.3 million to CalPERS, equal to 35% of base pay. And by 2025, the City of Pasadena is projected to pay $5.9 million to CalPERS, equal to 41% of base pay.

Can the City of South Pasadena afford to pay an additional three $3.0 million per year to CalPERS, on top of the nearly $3.0 million per year they’re already paying? They probably can, but at the expense of either higher local taxes or reduced public services, or a combination of both. But the story doesn’t end there. The primary reason required payments to CalPERS are doubling over the next few years is because CalPERS was wrong in their estimates of how much their pension fund could earn. They could still be wrong.

Annual pension contributions are calculated based on two factors: (1) How much future pension benefits were earned in the current year, and how much money must be set aside in this same year to earn interest and eventually be used to pay those benefits in the future? This is called the “normal contribution.” (2) What is the present value of ALL outstanding future pension payments, earned in all prior years by all participants in the plan, active and retired, and by how much does that value, that liability, exceed the amount of money currently invested in the pension fund? That amount is the unfunded pension liability, and the amount set aside each year to eventually reduce that unfunded liability to zero is called the “unfunded contribution.”

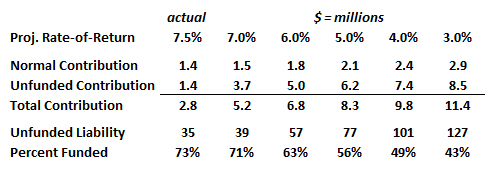

Both of these annual pension contributions depend on a key assumption: What rate-of-return can the pension fund earn each year, on average, over the next several decades? And it turns out the amount that has to be paid each year to keep a pension fund fully funded is extremely sensitive to this assumption. The reason, for example, that CalPERS is doubling the amount their participating employers have to pay each year is largely because they are gradually lowering their assumed rate of return from 7.5% per year to 7.0% per year. But what if that isn’t enough?

IF THE RATE-OF-RETURN CALPERS EARNS FALLS, PAYMENTS COULD RISE MUCH HIGHER

It isn’t unreasonable to worry that going forward, the average rate of return CalPERS earns on their investments could fall below 7.0% per year. For about a decade, nearly every asset class available to investors has enjoyed rates of appreciation in excess of historical averages. Yet despite being at what may be the late stages of a prolonged bull market in equities, bonds, and real estate, the City of South Pasadena’s pension investments managed by CalPERS were only 73% funded. As of 6/30/2017 (the most recent data CalPERS currently offers by agency), the City of South Pasadena faced an unfunded pension liability of $35 million. Using CalPERS own numbers, if they were to earn 6% per year on their investments in the coming years, instead of their new – and just lowered – annual return of 7%, that unfunded liability would rise to $58 million.

As it is, by 2025 the City of South Pasadena is already going to be making an unfunded contribution that is nearly twice their normal contribution. Another reason for this is because CalPERS is now requiring their participating agencies to pay off their unfunded pension liabilities in 20 years of even payments. Previously, attempting to minimize those payments, agencies had been using 30 year payoff terms with low payments in the early years. Back in 2017, based on a 6% rate-of-return projection, and in order to pay off a $58 million unfunded pension liability on these more aggressive repayment terms, the City of South Pasadena would have to come up with an unfunded pension contribution of $5.0 million per year, along with a normal contribution of around another $2.4 million per year.

But why should it end there? Nobody knows what the future holds. These rate-of-return projections by definition have to be “risk free,” since otherwise – and as has happened – taxpayers have to foot the bill to make these catch up payments. How many of you can rely on a “risk free” rate-of-return,” year after year, for decades, in your 401K accounts of six percent, or even five percent? At a 5% rate-of-return, the City of South Pasadena would have to pay an unfunded contribution of $6.2 million, along with a normal contribution of $2.8 million.

These scenarios are not outlandish. Most everyone hopes America and the world are just entering a wondrous “long boom” of peace and prosperity, ushered in by ongoing global stability and technological innovations. But the momentum of history is not predictable. Imagine if there was an era of deflation. It has happened before and it can happen again. The following chart shows how that might play out in the City of South Pasadena. Notice how at a 4% rate-of-return projection, in 2017 the City of South Pasadena would have had to pay CalPERS $9.8 million; at 3%, $11.4 million.

City of South Pasadena – FYE 6/30/2017

Estimated Pension Payments and Pension Debt at Various Rate-of-Return Projections

And what about the rest of California? How would a downturn affect all of California’s public employee pension systems, the agencies they serve, and the taxpayers who fund them? In a CPC analysis published earlier this year, “How to Assess Impact of a Market Correction on Pension Payments,” the following excerpt provides an estimate:

“If there is a 15% drop in pension fund assets, and the new projected earnings percentage is lowered from 7.0% to 6.0%, the normal contribution will increase by $2.6 billion per year, and the unfunded contribution will increase by $19.9 billion. Total annual pension contributions will increase from the currently estimated $31.0 billion to $68.5 billion.”

That’s a lot of billions. And as already noted, a 15% drop in the value of invested assets and a reduction in the estimated average annual rate-of-return from 7.0% to 6.0% is by no means a worst case scenario.

To-date, meaningful pension reform has been thwarted by powerful special interests, most notably pension funds and public sector unions, but also many financial sector firms who profit from the status quo. But a case to be decided next year by the California Supreme Court, Cal Fire Local 2881 v. CalPERS, may provide local agencies with the legal right to make more sweeping changes to pension benefits. The outcome of that ruling, combined with growing public pressure on local elected officials, may offer relief. For this reason, it may well be that raising taxes and cutting services in order to fund pensions may be a false choice.

REFERENCES

CalPERS Annual Valuation Reports – main search page

CalPERS Annual Valuation Report – South Pasadena, Miscellaneous Employees

CalPERS Annual Valuation Report – South Pasadena, Safety Employees

CalPERS Annual Valuation Report – South Pasadena, Miscellaneous Employees (PEPRA)

CalPERS Annual Valuation Report – South Pasadena, Safety Employees, Fire (PEPRA)

CalPERS Annual Valuation Report – South Pasadena, Safety Employees, Police (PEPRA)

Moody’s Cross Sector Rating Methodology – Adjustments to US State and Local Government Reported Pension Data (version in effect 2018)

California Pension Tracker (Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research – California Pension Tracker

Transparent California – main search page

Transparent California – salaries for South Pasadena

Transparent California – pensions for South Pasadena

The State Controller’s Government Compensation in California – main search page

The State Controller’s Government Compensation in California – South Pasadena payroll

The State Controller’s Government Compensation in California – raw data downloads

California Policy Center – Resources for Pension Reformers (dozens of links)

California Policy Center – Will the California Supreme Court Reform the “California Rule?” (latest update)

* * *