Long Overdue Financial Report for California Brings Bad News

When it comes to the reporting of the accounting of our 50 states, two main concerns can be observed. The first is the delinquency rate of several states. For the fiscal year June 30, 2022, 20 states released their audited financial statements within six months. There are four states that deviate from the norm, with one having a fiscal year ending in March, another in August, and two in September.

Eight more states issued their reports in January of 2023, two more in February, eight in March, two in April, one in May and June, three in August and one in October. Then the dribble stopped. No reports from California and Nevada until 2024, more than 18 months after the close of the fiscal year.

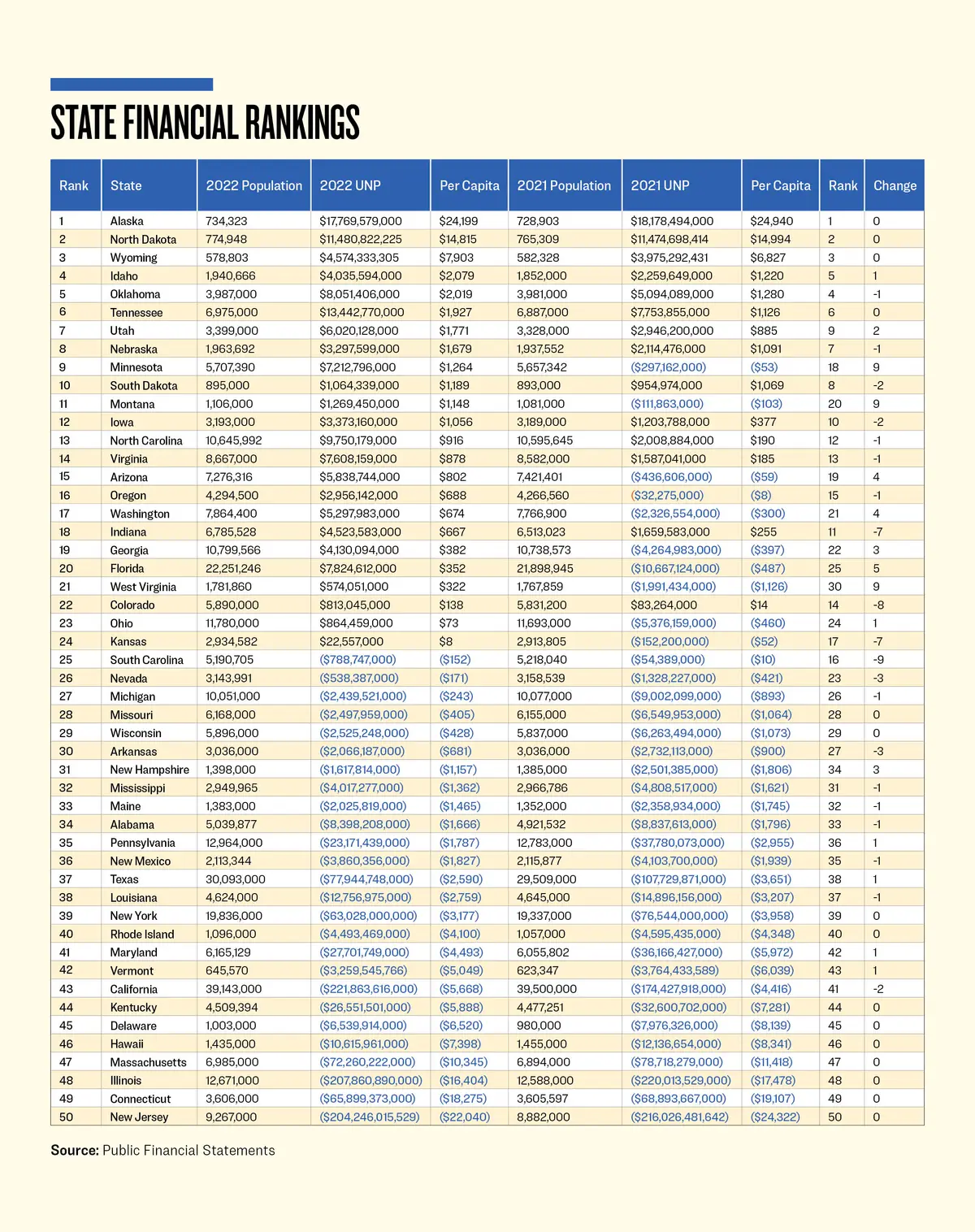

Taking the unrestricted net position for governmental activities from the statement of net position and dividing it by the state’s population, we derive a per capita that can be ranked. Now that we finally have all of the 50 annual comprehensive financial reports (ACFRs), we can see the full picture, and it is quite extraordinary.

Municipalities within a specific grouping usually don’t show much fluctuation year-over-year between their counterparts, rarely moving up or down by more than three positions. But 2022 saw six states jump up four or more positions and four drop seven or more. This means there are plenty of stories here, so let’s jump in. The big one being that now nearly half of the nation’s states are showing unrestricted net assets on their balance sheets instead of deficits.

Montana had $9.1 billion in revenues and $7.5 billion in expenditures, so it cleared $1.6 billion. This windfall took the state’s unrestricted net deficit of $111 million to a positive $1.3 billion. Minnesota had an $8 billion surplus, taking its unrestricted net deficit of $297 million to a positive $7.2 billion. West Virginia enjoyed $2.7 billion in revenues in excess of expenditures, taking a $2 billion unrestricted net deficit to a positive $574 million. All three states moved up 9 positions in the rankings.

Florida jumped up 5 positions. Its unrestricted net deficit in 2021 of $10.7 billion jumped to unrestricted net assets of $7.8 billion in 2022, an $18.5 billion increase. This was mainly due to revenues exceeding expenditures by $23.8 billion. If I were Gov. Ron DeSantis, I’d have the right to be a little cocky about the Sunshine State.

Washington also cleared nearly $8 billion and saw its unrestricted net deficit of $2.3 billion grow to a positive $5.3 billion. Arizona’s unrestricted net deficit went from $437 million to a positive $5.8 billion, thanks to $7 billion in revenues more than expenditures. Both states moved up 4 places.

Although not moving up in the rankings, those states at the bottom of the rankings made forward progress. Delaware’s unrestricted net deficit of $8 billion was reduced to $6.5 billion, thanks to $1.5 billion in excess revenues. Vermont’s revenues exceeded expenditures by $627 million, improving its unrestricted net deficit by $505 million.

While dropping one position, North Carolina improved its unrestricted net assets of $2 billion by $7.74 billion, thanks to $10.7 billion in excess revenues.

What was the secret sauce? Grants for human services. COVID-19 funding from the Federal government provided a dramatic shot in the arm. Florida received $35.2 billion; North Carolina $24.6 billion; Arizona $22 billion; Washington $19 billion; Minnesota $15.4 billion; West Virginia $6.5 billion; Delaware $3 billion; Montana $2.7 billion; and Vermont $2 billion.

The big question is: Why did four states drop by seven or more positions?

South Carolina received $7.2 billion in health and environmental grants, had $4.9 billion in excess revenues, but increased its unrestricted net deficit by $734 million. The main culprits were increasing debts by $2.4 billion from unearned revenues and increasing restricted assets by $1.6 billion. This resulted in dropping nine positions.

Colorado had $1 billion of revenues in excess of expenditures, but its unrestricted net assets only grew by $730 million. But when eight states formerly in deficit status jumped ahead of the state, it made Colorado drop eight places.

Indiana had $3.9 billion in excess revenues, growing its unrestricted net assets by $2.9 billion, but because states like Arizona, Montana, and Washington retained more of their federal coronavirus funding, Indiana dropped seven positions.

Kansas had $3.5 billion in federal grants, with $2 billion in excess revenues, but only increased its unrestricted net deficit to positive net assets by $175 million. The main reason was classifying $953 million as restricted. Kansas also dropped seven positions. But it would make it to the top 24 states that now have their balance sheets in positive territory.

California increased its unrestricted net deficit by $47.4 billion. Although it had $18.8 billion in revenues in excess of expenditures, thanks to receiving $140 billion in Health and Human Services grants, it still tumbled two places. It took California many years to move up to 41st place, and it is now back in 43rd. Its $222 billion unrestricted net deficit is the largest in California’s history and is also the largest in the nation.

There is good news—the unfunded actuarial accrued pension liability declined by $36.8 billion. But the other post-employment benefits remained at the $77 billion level.

The pandemic hit every state, and the response impacted them in similar manners. The story is how they managed the funds they received. As of June 30, 2022, it looked like the majority hung on to those funds and improved their balance sheets. But not California. With a governor who travels the world to brag about the Golden State, you can now understand one of the many reasons why the release of the audited financial statements was delayed until now.

This article originally appeared in The Epoch Times