Public education defunding drivel

The teachers unions and their allies demand more and more, and still more money for education.

In a recent New York Times piece, American Federation of Teachers President Randi Weingarten warned us about “The high cost of defunding public education.” Her standard issue whine starts off with the Time Magazine front-page story (which I wrote about last week) concerning a teacher who purportedly couldn’t make ends meet on her salary. But this time, instead of focusing on low teacher salaries, Weingarten aims at the bigger picture and insists that “lawmakers persistently underfund public schools.” She predictably lays the blame for this state of affairs on tax cuts for the wealthy and Education Secretary Betsy DeVos, of course.

To add to the doom and gloom, Weingarten cites a report by the Alliance to Reclaim Our Schools, a radical union-dominated group. (I’ve always wondered, “Reclaim it from whom?”) AROS alleges that “over $580 billion in authorized federal funding to support public schools, particularly in Black, Brown and low-income communities…has not been appropriated over the last 13 years alone.” In what amounts to a socialist manifesto, the “report” goes on to blame “the ongoing political proclivity for transferring public dollars to the nation’s wealthiest individuals and corporations.”

Okay, teachers union agenda time is over; here are a few facts you might want to keep in mind, should you be at a cocktail party and someone pops off about how public education is starving for funds. First, according to the National Center for Education Statistics, we currently spend about $668 billion dollars nationwide per year on public education. This puts us right at the top when compared to the rest of the world. In 2013, we were #1. Currently, we are third, a bit behind Switzerland and Norway.

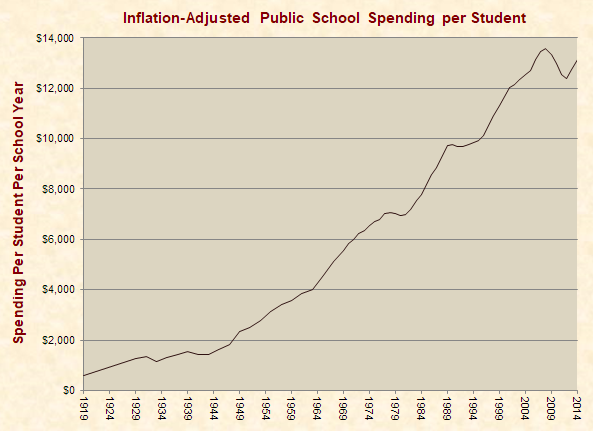

It’s also instructive to examine how our education spending has evolved over time. By listening to union leaders and others in the “we must spend more” crowd, you might think that we are investing much less on education than we used to, but nothing could be further from the truth. The following chart, courtesy of NCES and Just Facts, dispels the bunkum in a hurry.

As you can see from the above inflation-adjusted figures, we have increased our education spending over 17-fold in the last century. Also, as reported by the Cato Institute’s Andrew Coulson, who used data from the Digest of Education Statistics, we almost tripled our spending between 1970 and 2010 – and have absolutely no academic progress to show for it.

As for the AROS contention that the poor and minorities are getting shortchanged, that too is disproven by the data. The Heritage Foundation’s Jason Richwine explored alleged funding disparities right in the middle of the time period covered in the AROS report. The Myth of Racial Disparities in Public School Funding carefully examined the issue, and the hysterics were debunked at every turn. The study shows essentially no difference in funding for whites and blacks, or between the poor and the wealthy. In fact, Richwine writes, “To the extent that funding differences exist at all, they tend to slightly favor lower-performing groups, especially blacks.”

It’s important to note that while we don’t have an overall funding problem, many school districts do misappropriate money that could be spent much better elsewhere. As I wrote last week, researcher Benjamin Scafidi found that between 1950 and 2015, the hiring of non-teacher education employees in government run schools – administrators, teacher aides, counselors, social workers, etc. – rose more than 7 times the increase in students, while academic achievement has stagnated or even fallen over the past several decades. Scafidi writes that absent this mostly wasteful expenditure, our schools would have had an additional $37.2 billion to spend.

It’s time to stop blaming rich folks, tax cuts, Betsey DeVos, vouchers and charter schools for a funding crisis that doesn’t exist. If there are money issues – and there are in many places – state rules and regs need to be changed, and local school boards need to alter their spending habits. If Randi Weingarten truly wants schools to have more money “for the children,” one effective strategy would be to rein in her union which regularly makes impossible healthcare and pension demands at the state and local level. But she won’t; it’s so much easier to bellyache about rich people.

Larry Sand, a former classroom teacher, is the president of the non-profit California Teachers Empowerment Network – a non-partisan, non-political group dedicated to providing teachers and the general public with reliable and balanced information about professional affiliations and positions on educational issues. The views presented here are strictly his own.