Published July 7, 2023

The following was a three-part series that originally appeared in the California Globe on the impact of the California Environmental Quality Act on development in California and ways to potentially improve the law. It was written in response to hearings conducted over the past three months by California’s Little Hoover Commission.

What is CEQA?

The California Environmental Quality Act, universally known by its serendipitously phonetic acronym “SEE-kwa,” was passed by the state legislature in 1971. At that time, it was the first legislation of its kind in the nation, if not the world. Its original intent was to “inform government decisionmakers and the public about the potential environmental effects of proposed activities and to prevent significant, avoidable environmental damage.”

Over the past half-century, however, CEQA has acquired layers of legislative updates and precedent setting court rulings, warping it into a beast that denies clarity to developers and derails projects. When projects do make it through the CEQA gauntlet, the price of passage adds punitive costs in time and money. Knowing this will happen deters countless investors and developers from even trying to complete a project in the state.

Starting earlier this year, California’s nonpartisan Little Hoover Commission began studying the impact of CEQA and soliciting suggestions from the public. They have held four public hearings so far, on 3/16, 4/13, 4/27, and 5/11. The live hearings, lasting in total over 12 hours, in all four cases were attended by almost nobody apart from the commissioners and the people invited to testify. Altogether, so far on YouTube these four hearings have attracted just over 1,000 online views. Not much, considering CEQA’s impact.

Anyone who has waded through all 12 hours of these hearings may agree that certain themes came up again and again, and will doubtless factor significantly in determining what the commission ultimately recommends. The remainder of this report will summarize some of the recurrent or noteworthy observations and recommendations from these hearings, along with ideas solicited elsewhere from Californians that have had to deal with CEQA either as attorneys, judges, developers, or activists. To be clear, and in the interests of full disclosure, this report is not intended to offer a neutral perspective on CEQA. It is rather an attempt to further expose how problematic CEQA has become, and offer alternatives.

While CEQA is most often associated with housing, and is often cited as a major obstacle to building more housing in California, it affects any project that has potential environmental impacts. Along with housing development, this includes commercial development, sports facilities, and all types of infrastructure including dams, aqueducts, wastewater treatment plants, desalination plants, power plants, power transmission lines, pipelines, ports and port upgrades, rail, road, mines, quarries, logging, land management; anything that changes land use and may cause “significant” environmental damage. And in every case, the influence of CEQA has its champions and its detractors.

What may inform CEQA judgments has changed over the decades. In one of the first of the Little Hoover Commission’s hearings, a panelist informed the group, speaking with almost reverent certainty, that five of California’s major airports “would be underwater by 2050.” Such remarks and sentiments now pervade CEQA proceedings. Climate change impact, which was absent from CEQA cases in the 1970s, has become one of the dominant concerns brought in CEQA cases today.

The Labyrinth Called CEQA

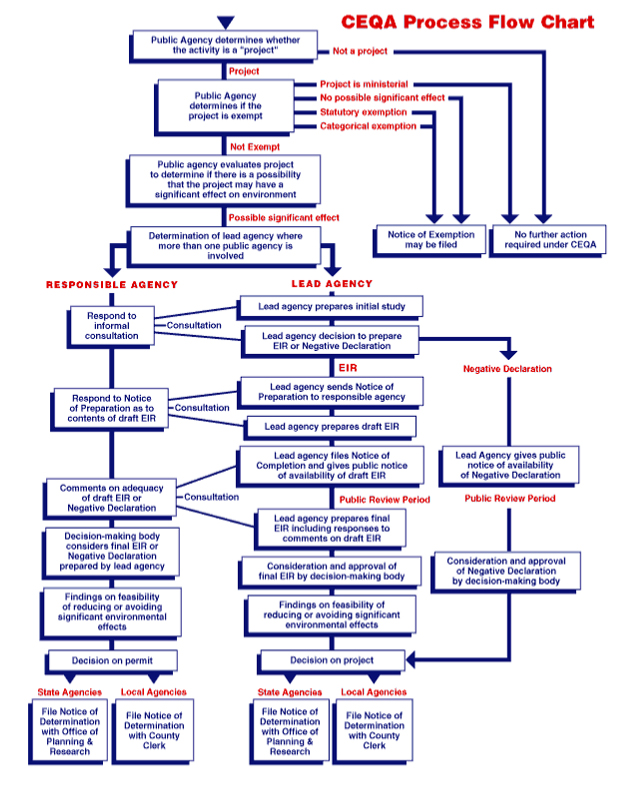

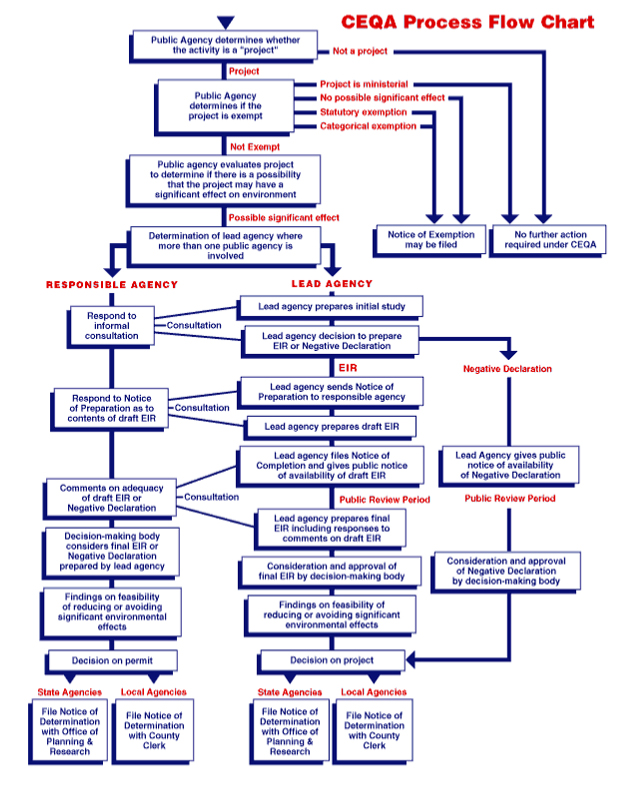

The concept of CEQA is unassailable. If a project may cause “significant impact” to the environment, the CEQA process will ensure that either the impact is appropriately mitigated, or the project is stopped. The chart depicted below, courtesy of the California Department of Conservation, depicts the CEQA process. If anything, this elaborate flow chart understates what a project developer is up against thanks to CEQA. There is rarely just one “responsible agency.” If any of these agencies determine there are any flaws or omissions in the required “Environmental Impact Report” (EIR), the process often has to be restarted. The delays between inter-agency responses can consume months if not years. The “public review period” leaves room for a 3rd party to file a time consuming lawsuit right up to the last minute before a project is finally approved.

If the complexity of CEQA as depicted in this flowchart makes obvious the difficulties facing anyone who develops property or manages land, it also explains why exemptions have become the shortcut taken for politically favored projects. Exemption from CEQA has been the default remedy pursued by the state legislature whenever they decide it is important to prioritize any project, or category of projects. But carving out one exemption after another does not fix CEQA. Even if the state legislature were capable of correctly prioritizing projects, which is an absurd reach, it remains an absolute process without gradation. Anointed projects skip through the exemption portal and are fast-tracked, even though many of them may cause environmental impacts that are significant. Meanwhile, all other projects, many of which are just as urgently required, must go through the labyrinth called CEQA.

Would True Environmental Justice Include More “Greenfield” Development?

Along with the relatively new and central role of climate change impact in the CEQA process, another major new concern now considered in CEQA cases is “environmental justice,” that is, the alleged disproportionate effect development projects may have in low income neighborhoods. This allegation is not unfounded, although the causes predictably attributed to this – a legacy of systemic racism – are more nuanced than conventional wisdom may acknowledge. Residential areas that are situated in close proximity to a network of freeways, industrial parks, airports, seaports, and warehouse districts, for example, are going to have more noise and more air pollution than residential areas that are in the foothills peripheral to a major urban center. Homes and apartment rentals in less desirable neighborhoods will be more affordable, so it is natural that on average, residents with lower household incomes will be living there. Campaigns for environmental justice can be based solely on economics without sacrificing credibility or moral worth.

Regardless of the underlying causes, it is valid to argue that yet another industrial project in a neighborhood that already has a high density of industrial development is going to add its incremental contribution of noise and pollution to a place already saturated with noise and pollution, whereas putting that same project in a pristine affluent suburb will not. It is also valid to argue that the residents and elected officials in wealthy neighborhoods have the economic wherewithal to hire attorneys to litigate against industrial projects and high density housing in their neighborhoods, whereas these same projects can be directed into lower income neighborhoods where the residents do not have the resources to resist.

This gives rise to a criticism of CEQA that is double edged. On one hand, CEQA offers people in low income communities one of the only legal tools available to fight high density housing and industrial or warehouse development that will create more noise, more congestion, more of a service burden, and more pollution in their communities. But at the same time, while residents in these low income communities have to find an attorney willing to carry their objections, often pro bono, into a legal battle, CEQA is an off-the-shelf, potent weapon in the hands of wealthy residents across town, who deploy it at will to keep high density housing and unwanted commercial development out of their communities.

One solution to this conundrum which some would consider a win-win would be to develop entire new cities on open land in California. Doing this would preserve the ambiance of existing neighborhoods, regardless of their average household income, and might even facilitate de-densification. It would lower the price of housing everywhere, making it easier for low-income residents to afford to either improve their neighborhoods or migrate to new communities. Doing this, however, would require massive state investment in enabling energy, water, and transportation infrastructure. Back in the 1950s and 1960s, building enabling infrastructure was something the state made a budget priority and performed remarkably well. Today, California’s state government has not made infrastructure investment a sufficient priority, and this failure to maintain and expand California’s infrastructure is frequently blamed on the roadblocks thrown up by CEQA.

Should densification and rationing be the only answer to environmentalist concerns? This question should be faced honestly. Is it impossible to construct new infrastructure to enable suburban growth? Why? California is a big state, with thousands of square miles of land that seems to be ripe for carpeting over with sprawling wind and solar farms, while new homes and new roads remain anathema. There’s room for both. California’s urban footprint consumes about 8,000 square miles, which is only about 5 percent of its area. You could build new cities housing 10 million people on raw open land, in four person households in single family dwellings on quarter-acre lots, with an equal amount of space allocated for roads, schools, parks, and commercial and industrial space, and it would only require 2,000 square miles. In the geography of vast California, that is an insignificant amount of land. Why not?

It is ironic that CEQA and related laws have made it almost impossible to build on “greenfields,” that is, on raw undeveloped land on the periphery of cities, and yet the laws are streamlined to fast-track infill development in relatively toxic and already densely populated urban environments. Perhaps in the interest of environmental justice, low income communities should be supporting laws to permit the expansion of California’s urban footprint.

The Tentacles of CEQA Intersect with Other Regulatory Beasts

It’s easy to digress into a discussion of urban planning, and ask why a green straightjacket has been thrown around every major urban center in California, but at the center of such a tangent one still finds omnipresent CEQA. And CEQA, for all of its regulatory tentacles, is only part of a consortium of similar regulatory creatures. The Endangered Species Act, the National Environmental Policy Act, the California Global Warming Solutions Act (AB 32, passed by the state legislature in 2006), and seemingly infinite laws, executive orders, agency regulations, and court rulings pursuant to these and others, along with CEQA, have combined to make development in California nearly impossible.

For example, development proponents who testified in the Little Hoover Commission hearings repeatedly brought up a relatively recent regulation pursuant to AB 32, the requirement that any new housing development calculate the projected annual “vehicle miles traveled” (VMT) the residents will generate. Taking effect in 2018, this new analysis must be done in order to determine how much mitigating fees the developer will be assessed in order to fund mass transit or otherwise offset the anticipated greenhouse gas emissions from vehicles owned by residents of a new community.

But in the meantime, developers whose projects have been mired in the CEQA process since well before 2018 are now required to supplement the portions of their EIR that evaluated traffic impacts based on congestion with a new evaluation that estimates vehicle miles traveled. And while this VMT analysis is meant to supersede the traffic congestion as “the new lens for assessing transportation impacts,” potential congestion remains grounds for 3rd parties use CEQA to sue developers to stop their projects.

More generally, critics of CEQA have made clear that the law, in combination with other environmentalist inspired laws, have created a web of regulatory hurdles that are so unclear and so costly that only a small handful of housing developers, government agencies, or civil engineering contractors are big enough to navigate them. As one person testifying said, CEQA will turn a $1.0 billion project into a $1.5 billion project simply because when it takes ten years to go through the typical rounds of CEQA reviews, then debt financing taken out at 5 percent interest after 10 years will have ballooned up to a sum more than 50 percent higher than at the start.

Another compounding problem with CEQA and related laws designed to protect the environment is because so many years are required to get approval, by the time the design of a project is approved, the design has become obsolete.

Changing the rules in midstream, conflicting rules depending on the agency, an approval process that takes years if not decades, financing that dries up or is driven up to punitive levels, excessive, unreasonable fees, projects that take so long that if and when they finally get the green light, either the market or the technology has left them far behind. Start over. This is life with CEQA. This is California. For all its virtues, and there are plenty of them, environmentalism run amok is destroying economic opportunities for all Californians, and CEQA is the beating heart of the beast.

The Exemptions Cop Out

One solution to CEQA’s hurdles is to declare exemptions, and California’s state legislature has done this again and again. Sports stadiums. Low income housing. Transportation projects. But what if other projects – vital public infrastructure projects and major private developments – are just as legitimately in need of relief from CEQA and are just as vital to the economic health of California and its people?

At one point the Hoover Commission panelists seemed to agree that instead of revising CEQA, they might just agree on what sorts of project categories should be exempt. This mentality was evident as well in the recent legislative package submitted by Governor Newsom that would have streamlined the CEQA process for vital infrastructure. Killed almost immediately in committee, Newsom’s bills in any case were picking winners. If you want 10 megawatt wind turbines floating off the northern coast, or giant solar farms in the Mojave Desert and South San Joaquin Valley, you would like Newsom’s proposals. If you want more “affordable housing,” where both the needlessly overpriced construction cost and the eventual rental payments by occupants are subsidized by taxpayers, Newsom’s proposals were great policy. Put another way, if you want to burden taxpayers with heavily subsidized, overpriced energy and housing, you may adhere to the prevailing wisdom on CEQA, which is to identify what to exempt from CEQA, favor those project categories, and let everything else continue to wither under an unreformed body of law.

Instead of carving out specific exemptions to CEQA, why not eliminate all exemptions? That might drive all the politically connected special interests back to the table, focusing their minds on what parts of CEQA can stay and what can be scrapped. According to Dan Dunmoyer, president of the California Building Industry Association, back in the 1970s a CEQA report that was only two pages is, today, going to require over 1,000 pages. Dunmoyer said that for a typical 200 home subdivision project the developer can expect to spend at least $1.0 million on CEQA reports in a process that will take 2-3 years, and that’s best case. If there is any litigation, those budgets and timelines go out the window.

One of the most articulate critics of CEQA in the Little Hoover Commission hearings was attorney Jennifer Hernandez, who offered a blistering rebuke of the “infill” mantra that streamlines the process for “tiny homes” and “accessory dwelling units.” Explaining that “welders cannot bike to work and should not have to live in a backyard cottage,” Hernandez suggested that the conversation about CEQA needs to include working people who have practical needs for affordable utility bills, practical transportation infrastructure, and good jobs. She’s right. The impact of CEQA on the price and availability of essentials – housing, water, energy, transportation – imposes direct and often crippling costs on residents. At the same time, California’s politically contrived, uncompetitive prices for land, utilities, and CEQA driven regulatory costs also deters companies from locating in California, or remaining in California, also depriving Californians of job opportunities.

While CEQA debates focus on how to streamline the process to get more renewable energy and subsidized housing, these deliberations ignore the fact that exempting renewables and low income housing actually increases the tax burden on workers who already confront a cost-of-living that is artificially elevated thanks to CEQA. As Hernandez put it, “we are expelling people from California.” Population decline for three years in a row in California, for the first time since statehood was achieved, backs up that statement. It isn’t the weather.

The Use and Abuse of CEQA

Several people addressing the Little Hoover Commission brought up the problem of abuse. Hernandez characterized CEQA as a body of law so complex that uncertainty is inherent and outcomes to litigation cannot be predicted. Lawsuits without merit often win and meritorious lawsuits often lose. Judges will often find just one unforeseeable part of a CEQA report that has fallen short of what they believe is required and send the applicant back to do it all over again. She claimed there is no area of law that has the level of uncertainty of CEQA. She claimed that almost half of California’s production of housing was sued in 2022.

For developers, the almost inevitable arrival of a lawsuit has turned CEQA, as Hernandez described it, into a “litigation defense tool.” The applicant tries to anticipate and answer in advance every conceivable objection to their project, which is, thanks to the complexity of CEQA, an impossible task. Then so-called bounty hunters pounce as soon as the application is filed. Lawyer trolls who identify a crack in the CEQA report and threaten to sue. Settling with these attorneys becomes another cost of doing business.

In CEQA lawsuits today, “significant impact on the environment” has never been defined more broadly. This opens up avenues for litigation that are available not only to environmentalists who may or may not have a legitimate concern about the project’s impact on the environment. It also invites lawsuits from parties with ulterior motives. Labor unions that want the developer to accept a project labor agreement often file CEQA lawsuits, a practice that has come to be referred to as “greenmail.” Business interests that compete with a project developer will often file CEQA lawsuits.

It’s important to recognize how CEQA is abused by special interests with an environmental concern that is indirect at best, but CEQA’s impact is abusive in ways that are explicitly environmentalist. When attorneys representing environmentalist organizations spoke to the Little Hoover Commission panel, their observations reflected what might be characterized as demanding the impossible.

In particular, one environmentalist in their testimony claimed that CEQA prevents housing from being foolishly built if there isn’t any available supply of water for those homes, and that CEQA keeps housing out of fire zones. But it is CEQA that prevents water supply infrastructure from getting built, and it is CEQA that prevents mechanical thinning, controlled burns, and responsible logging in order to prevent dangerous buildup of fuel in forest and chaparral where natural, forest thinning fires have been suppressed for decades.

Some of the environmentalist objections invited immediate rebuttal. One environmentalist explained that “uncontrolled sprawl” cuts into wildlife habitat, harming mountain lions. But only 5 percent of California’s land is urbanized, and California’s mountain lions are thriving. An analysis released by the U.S. Dept. of Agriculture in 2020 estimated that California’s population of mountain lions has grown from less than 600 prior to gaining protected status to over 6,000 today. But this fact is unconvincing for environmentalists who are intent on preserving and increasing mountain lion populations in every subregion of the state.

This preservationist mentality is not limited to mountain lions, of course. Environmentalist lawsuits are filed to stop projects that may threaten the habitat of any species, or subspecies, not only of animals, but also of plants. There is nothing inherently wrong with wanting to save mountain lions, or, for that matter, any species of animal or plant, anywhere. How environmentalists have worked to save the California Condor from extinction is an inspiring story. But the values and priorities of environmentalism must be balanced against the consequences of denying, delaying, and driving up costs for development. And it is ironic, at best, that CEQA exceptions are proliferating for solar and windfarm sprawl, while badly needed housing and vital enabling infrastructure that might consume far less of the “urban/wildland interface” remain under the debilitating scope of CEQA.

Solutions to CEQA

What was never mentioned in the Little Hoover Commission’s hearings on CEQA, but deserves consideration, is to simply repeal the entire law. Get rid of it. The idea that development projects would suddenly proliferate, out of control, if CEQA went away is ridiculous. Every other law to protect the environment would still be in place, including the Endangered Species Act, the Global Warming Solutions Act (which should also be repealed), and the National Environmental Policy Act, which is the federal counterpart to CEQA and which is more than adequate to protect the environment.

Eliminating CEQA would go a long way towards restoring opportunities for low and middle income Californians, but eliminating CEQA is a fantasy. Equally impossible would be to eliminate the ability of private parties to sue developers under CEQA. This would eliminate the bounty hunters and lawyer trolls who have created a lucrative industry using CEQA to shake down developers. While it would also remove an avenue for members of low income communities to protect their neighborhoods, that benefit is overstated when developers target low income communities for high density housing, protected by laws that have exempted them from CEQA, and also permit them to circumvent local zoning restrictions. There is another path to environmental justice, which is to lower the cost-of-living, and the biggest barrier to lowering the cost-of-living is CEQA.

A solution to CEQA that might be politically viable would be to restrict 3rd party lawsuits to parties that are specifically concerned about environmental impact and reside in the affected communities. This reform, if it was properly calibrated, might reduce or eliminate greenmail, lawsuits brought by competitors to a developer, and settlement bounty hunters. Another solution, mentioned earlier, might be to eliminate all exemptions, and recognize that if CEQA is a necessary process to protect the environment, there is no justification to place any category of development outside its purview.

Here then, are some incremental, and not so incremental, solutions proposed for CEQA:

1 – Eliminate all exemptions. Anyone wanting an exemption is speaking just for their special interest.

2 – End anonymous lawsuits; require environmental standing to sue. Accept only environmental criteria for litigation. Only allow standing to people directly impacted on environmental grounds. For example, NEPA does not give standing to labor.

3 – Clarify the conditions under which if a development conforms to a county’s standing environmental impact report for that category of project, then it is not subject to further CEQA review.

4 – Allow applicants to rely on previously approved EIR. If a proposed project is consistent with the county’s specific general plan, community plan. and zoning, eliminate the requirement for additional environmental review.

5 – Make reviews of housing projects ministerial, or, make review of any project – including energy development – ministerial.

6 – Require the loser in CEQA lawsuits to pay the prevailing party’s legal fees.

7 – End duplicative lawsuits; once a plan or project is approved with CEQA it can be challenged in a lawsuit once but not multiple times for each subsequent agency approval.

8 – Do the CEQA process just once, with all involved agencies operating together, not sequentially.

9 – Change the timeline for notifying agencies of the objections to EIRs. Designate a final review step in the CEQA process after which further litigation is prohibited. This is already a provision of NEPA. As it is, objections including litigation are filed at the last possible moment, often in the final public hearing before approval of a project.

10 – For all private proposals, eliminate the requirement that the EIR include an evaluation of alternative sites for the project.

11 – Impose a maximum time limit on how long an agency has to respond to an initial or revised environmental impact report.

12 – Expedite the process so problems identified in an EIR review can be fixed right away by the developer. As it is every time the process is restarted there is potential for new claims.

13 – Match the CEQA remedy to the CEQA deficiency. Specify that while a court can order more CEQA analysis and mitigation, it cannot block a project or rescind a project approval unless there is a significant adverse health or safety impact if the project is constructed.

14 – Flaws found in EIRs are often extremely technical and it is often questionable whether or not a particular technical deficiency would prevent the project from being approved in its current form. Therefore if there is a technical flaw but it is not prejudicial and will not really make a difference, a harmless error standard should apply, such that if the project would be approved anyway notwithstanding the technical deficiency that should not be a basis for denying the EIR.

15 – Judicially enforce California Public Resources Code PRC § 21083.1. Judges should not require anything more than what is expressly required in CEQA statutes and guidelines. Doing this would make CEQA more predictable, which would improve the law and its effect on development.

16 – Replace the right to appeal with the right only to a writ of mandamus. This way if the court of appeal believes the appeal is frivolous they can deny the writ and hence avoid a full briefing, oral arguments, and having to write an opinion. A writ of mandamus can be evaluated within months. If an appellate court does think an appeal has merit, they can approve a writ of mandamus and then it becomes treated like an appeal. The reform language can include a provision that if there is a “likelihood” the petitioner is right, the appellate course must accept the writ.

17 – If a project is approved, that approval shall remain recognized for a set number of years even if rules are subsequently updated.

18 – Repeal CEQA entirely. Rely on NEPA and other environmentalist legislation to protect the environment from developments that may have a significant impact.

The Benefits of CEQA Reform

Despite objections from environmentalist organizations, environmental justice advocates, and some labor union representatives, there is a growing consensus within the State Legislature that something has to be done about CEQA. This is evident in the countless exceptions that the legislature has enacted to accelerate development of low income housing and renewable energy projects.

One of the most intriguing testimonies before the Little Hoover Commission came from Danny Curtain, representing the California Conference of Carpenters. He argued that a labor union is justified in seeking prevailing wages and a project labor agreement whenever a private developer receives public subsidies and streamlined permitting benefits. As he put it, “if you give the developer a break don’t let the developer take out profits on the backs of the workers.”

Curtain’s point is that if there is a special public benefit then you can argue the public sector now has equity in the project and therefore you can argue it is to some extent a public work and therefore should be subject to the labor laws impacting public works. This is a reasonable argument. One may object to the idea that public works should be subject to project labor agreements at all. But that is a separate debate.

The role of unions in CEQA raises a more fundamental question. How do you bring construction workers, or, for that matter, all skilled workers, back into middle class status? Do you accomplish this via union mandates or via business competition for workers in a prospering economy? As it is, there is a shortage of highly skilled workers, ready to take on more public works projects or work in California’s industrial sector. Where are the apprenticeship programs to address this shortage?

One of the last people to speak was involved with the Sierra Club, who proudly declared they “go to sleep with EIRs.” This person, and countless similarly committed activists and professionals, have become expert at using CEQA to stop projects. Whether it is housing, or critical enabling infrastructure, seemingly no major project, anywhere, is acceptable to them. CEQA is their weapon to stop California from building the physical assets to match its population. And for years, with increasing effect, it’s been working.

This is where unions, if they’re serious about seeing more workers acquire middle class status, may want to consider the upside of diminished CEQA statutes. If California’s civil engineering contractors were permitted to build practical solutions to supply the state with abundant energy and water, not only would this create tens of thousands of high paid construction jobs for highly skilled workers, it would lower the cost-of-living for every household in the state.

There are two paths to financial security for households. The traditional union solution is the path of higher wages. But an equally effective path with broader benefit is to lower the cost of life’s essentials – housing, water, energy, transportation and food. Union leadership in California should consider the impact of CEQA in this context, and if they do, realize their alliance of convenience with environmentalist extremists is not in the interests of all workers, even if it has worked to the more narrow benefit of their own memberships.

Reducing the power of CEQA may be the first of many steps necessary to rescue California from a mentality of scarcity and rationing that, to-date, has only been challenged rhetorically. Declaring more exemptions to CEQA is a terrible solution. The many steps recommended here may fall well short of a complete repeal of the law, but would all nonetheless help make California a place where working families may have a better chance to find a good job, afford to pay their bills, and begin to achieve financial security for their households.

CEQA reform, however, is only one big part of a much bigger debate. Do Californians want to develop their state again with the confidence and efficiency that defined the big projects of the 1950s and 1960s, when roads, reservoirs, and a power grid were constructed using mostly public money and for a time actually delivered an oversupply of affordable transportation, water and energy? Do Californians want to set an example that other nations of the world find attractive and practical? Because to do that, more than CEQA will have to be revised.

For example, modern natural gas power plants employ combined cycle designs that harvest waste heat from the natural gas-fired turbine to produce steam to drive a second turbine. But new combined cycle designs replace the steam with helium, which harvests waste heat at much higher temperatures than steam can, which means less heat wasted to the atmosphere, greatly increasing efficiency. The natural gas fueling these advanced designs can be blended with carbon neutral combustible fuel, such as methane harvested from landfills. Why not qualify these new ultra-efficient powerplants as renewable energy?

For that matter, why aren’t Californians at the forefront of both small modular and large next-generation nuclear reactor development, and reclassifying them as renewable energy?

Why can’t advanced, still emerging hybrid automotive technologies, which use a battery one-tenth as heavy to harvest the energy otherwise wasted from braking and downhill momentum, remain eligible for sale in California after 2035?

Why isn’t the California Water Commission required to declare “beneficial use” of water diversions to be equally applicable to urban and agricultural users as it is when allocated to preserving aquatic ecosystems?

Answering questions like these with policies that are once again designed to nurture economic growth instead of economic stagnation is a prerequisite for California to recover prosperity for every worker in the state. Unions should recognize this, as should social justice activists and progressives. The impact of CEQA in particular, and overwritten environmentalist legislation in general, only benefits special interests. It is time to restore balance between what is possible to protect the environment, and what is necessary to empower the people living here. Reforming CEQA is the first step in that process.