San Diego’s 2012 Pension Reform at Risk

“The ruling is also an implicit endorsement of the state Public Employment Relations Board’s conclusion that the employees hired since the measure took effect must be made whole and get a pension equivalent to what they would have received pre-Proposition B.”

– Editorial, San Diego Union Tribune, March 18, 2019

The ruling in question is the California’s Supreme Court’s August 2018 decision which found that “San Diego’s six-year-old pension cutbacks were not legally placed on the ballot because city officials failed to negotiate with labor unions before pursuing the measure.” It’s in the news again this week because the U.S. Supreme Court has just announced they will not hear the City’s appeal of the California ruling.

What’s going to happen now is uncertain. Back in 2012, a super-majority of San Diego voters, 65 percent, approved pension cuts for new employees, putting all but police hires onto 401K plans. The union immediately appealed, claiming that since one of the proponents of the ballot measure was the mayor, it was necessary to “meet and confer” with the unions before asking the voters to change the pension benefits that new employees would receive.

The trajectory of this case is complex. Back in 2012, the unions challenged the voter approved reforms before the union-stacked Public Employee Relations Board, which in 2015 ruled in their favor. Then the City of San Diego got PERB’s ruling overturned in 2017 in state appellate court. Which brings us to round three, back in August, won by the unions in the State Supreme Court. But opinions differ as to what will happen next.

As the San Diego Union-Tribune opined in their editorial, the State Supreme Court “implicitly endorsed” the PERB ruling that invalidates the voter approved reforms. But some of the original proponents disagree.

One of the attorneys who has represented the proponents, Kenneth Lounsberry, in an email, wrote:

The State Court didn’t need to “invite” a position on the validity issue, which was heavily briefed in the moving papers. If the high court wanted to invalidate the measure, it would have done so. It is likely, based on oral argument, that the Court of Appeal WILL NOT invalidate Prop B. The true remedy in this case is a process. The City, according to the State Court, should have met and conferred; abiding by the process. The remedy – make them meet and confer. But, do not speculate about the outcome – the result – of meeting an conferring. No one, least of all the Court of Appeal, needs to conjure a RESULT. The result will the product of painful and extended negotiations that must include a fiscal analysis of the potential outcomes. We’ll see if the unions have the stomach for urging municipal insolvency.

Municipal insolvency indeed. More to the point, higher taxes for less service, thanks to pensions. Why else would two thirds of San Diego voters have supported this reform? Questioning the validity of Prop. B is based on an oversight that wouldn’t have changed the outcome. Would this have been challenged if the proponents had not included the mayor? So what if the mayor was included as a proponent? What about free speech? Can the mayor not take a policy initiative to the voters? So what if the mayor did not “meet and confer?” Would the outcome have been different? Of course not. The unions would have refused to accept the proposed reform, the “meet and confer” condition would have been met, the proponents would have gone on to place Prop. B on the ballot, and the voters would have approved it.

What kind of money are we talking about, anyway? If Prop. B is invalidated next month, as the case returns to the appellate court, the cost of “making whole” the 4,000 employees hired since pensions were eliminated is estimated to range between $20 and $100 million. The financial precedent going forward is likely more significant than the actual cost of catching up – $100 million could be financed at 6 percent for 20 years at $8.7 million per year. The pushers of pension obligation bonds would be happy to step up and take care of that for the city. With general fund revenues for 2019 estimated to be nearly $1.1 billion (SD CAFR, page 15), they can afford another $8.7 million. Or can they?

The City of San Diego’s financial statements for FY 2018 report pension payments of $325 million (SD CAFR, page 192), which is 72 percent of pension eligible payroll. Seventy-two percent. To put this in perspective, private sector employers pay Social Security taxes equivalent to 6.2 percent of payroll, plus, in increasingly rare cases, maybe a 3.0 percent matching contribution to a 401K plan.

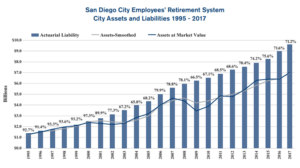

With all that money pouring into the City of San Diego’s independent pension system, how are they doing? Presented below is a chart from their 2018 financial report (SDCERS CAFR page 91) that shows their funding status. As can be seen, the size of the plan’s liability, which is the present estimated value of all promised future pension payments (vertical axis) has exploded, thanks to pension benefit enhancements enacted starting in the late 1990s. The pension liability was around $1.3 billion in 1995, and it grew to around $9.6 billion by 2017.

To be fair, the City of San Diego’s population grew by 22 percent between 1995 and 2017, and the consumer price index inflated by 61 percent. Taking those factors into account, the pension liability should have increased by 96 percent, up to $2.5 billion. It’s 370 percent higher than that. We can thank the public employee unions, and their powerful accomplices, the pension fund lobbyists, for benefit enhancements that have piled nearly $10 billion of pension debt onto the taxpayers of San Diego.

How much of that is covered by assets in the pension fund? Again, the chart shows that trend. Back in 1995, the pension liability was 92.7 percent covered. There was roughly $1.3 billion in liabilities, and roughly $1.2 billion in invested assets. What about 2017? How are they doing? As the chart indicates, only 71.2 percent, or about $6.8 billion, is available to cover $9.6 billion in pension liabilities. The city is $2.8 billion in the hole.

Another way to put this all into perspective is to look at the actual pensions being paid by the City of San Diego. According to Transparent California, the average pension for a retiree with 30 years of full time work was $85,670 in 2017.

That average is skewed upwards to include DROP payments, an amazing boondoggle that San Diego offers along with many other California cities. The “Deferred Retirement Option Plan” (DROP), allows pension eligible employees to start collecting their pension (paid into an interest bearing account) while they continue to work. When they finally do retire, that lump sum is paid to them in their first year of retirement, along with the ongoing pension payments. Have a look at the City of San Diego’s individual pension payments courtesy of Transparent California.

Wherever it says “see note” you can see how much DROP payments each of them collected. The 2017 champion is Diane Silva-Martinez, who collected a lump sum of $824,300 when she “actually” retired. Note most 2017 retirees receiving DROP payments probably were not retired the entire 12 months of 2017, so the imputed net amounts of their actual 2017 pensions are usually understated.

And if you don’t include DROP payments, how much does the average City of San Diego employee receive as a pension? The San Diego City Employees’ Retirement System financial report for FYE 6/30/2018 offers clues. Page 131 shows that in 2017 there were 9,768 retirees collecting an average pension of $48,199, based on an average retirement age of 56, and average “service years” of 24. On page 132 of the SDCERS financial report you can see retiree pensions sorted by years of service and final monthly salary. The average retiree with 26-30 years of service had an average salary of $82,728 and received a pension of $67,968. These pension averages don’t include other benefits such as retiree health care, but are these “modest” pensions? That depends on what you’re comparing it to. Social Security provides a good comparison, since that’s what the San Diego’s private sector taxpayers get.

If you go to the “Social Security Quick Calculator” and input an average final salary of $82,728, a retirement date of April, 2019, and a birth date of 1949 – which means you worked till the age of 70 – your estimated Social Security payment is $32,016 per year. That’s modest. A good rule of thumb when comparing Social Security to public sector pensions in California is “work twice as long, collect half as much.” And of course never forget that independent contractors pay 12.4 percent of their gross earnings into the Social Security fund. Examples of public employees who have 12.4 percent or more withheld from their paychecks are few and far between, if there are any at all.

How did it come to this? An excellent analysis of San Diego’s pension enhancements and the financial havoc they were creating was written in 2014 by Adam Summers and Lance Christensen and published by Reason. While five years old, the report nails the history, and deserves reading in its entirety by anyone wanting a more thorough understanding of what led up to the present situation. Here is a relevant excerpt:

“The average San Diego city employee’s pension more than tripled between 1996 and 2013. The average city pension for employees who had worked over 30 years was nearly $64,000 in 2012. The increase in retirement costs is due, in large part, to several lavish benefits—including a program for “double-dipping” (the Deferred Retirement Option Program (DROP), purchasing years of service that were not worked (“air time”), receiving extra pension checks, and employer-matching savings plans—added to an already generous retirement package.”

California’s public employee pensions are not sustainable. Moving new employees to 401K plans was a financially sound option because it put a cap on the city’s obligation. There are many ways to restore financial sustainability to California’s public employee pensions. Voters are likely to overwhelmingly support any of them. What happens next in San Diego bears watching.

* * *

Edward Ring is a co-founder of the California Policy Center and served as its first president.