The Abundance Choice – Part 14: Infinite Abundance

Editor’s note: This is the fourteenth article in a series on California’s water crisis. You can read the entire series including recent updates in his new book “The Abundance Choice, Our Fight for More Water in California.”

From the inaugural Stanford Digital Economy Lab gathering in April 2022, noted venture capitalist Steve Jurvetson posted the following quote to Facebook: “Our goal is to usher in an era of infinite abundance.”

“Infinite abundance.”

This phrase epitomizes the ongoing promise of California’s tech culture. Despite every political shortcoming California may suffer, its technology sector continues to set the pace for the rest of the world. “Infinite abundance,” evocative of an earlier tech mantra “better, faster, cheaper,” is not only a defining aspiration of tech entrepreneurs, it is closer to being realized every day.

So why is it that Californians can’t generate abundant electric power? Why is it that Californians can’t figure out how to deliver abundant water? And how does a future of rationed, scarce energy and water square with the dreams of infinite abundance that inspire every one of California’s high tech entrepreneurs and investors? And insofar as the political clout of California’s high tech sector gives it almost infinite influence, when will its high-tech innovators confront this paradox?

For almost every significant resource of consequence to normal working families – energy, water, transportation, housing, and food – ordinary Californians have been betrayed by their elected officials. Everything is running out. Everything costs too much. But when Californians realize that the punitive cost-of-living they’ve endured was the result of poor political choices, and not an inevitable “new normal” they will need to be presented with alternative policies.

Somewhere between the grenade throwing pundit who persuasively condemns everything that’s gone wrong, and the confirmed wonk whose turgid policy prescriptions are never read and typically stay within rigid ideological lanes, we need more people who will instead try to propose practical solutions. Straying well afield of both the complaining cynic and the lost-in-the-weeds wonk, last year I attempted to recruit a team of experts to come up with a policy solution to water scarcity in California. Despite our effort to qualify our initiative getting crushed in its cradle, I believe we succeeded.

The Water Infrastructure Funding Act, unaltered, would have created water abundance in California. Even an attenuated version of this initiative, with a few key elements removed but largely intact, would dramatically improve California’s water supply challenges. But if most of California’s financial special interests oppose water abundance, and powerful environmentalist organizations appear unwilling to support any big new water infrastructure projects, how will Californians ever escape high water prices and rationing?

More generally, if abundance in all things harms financial special interests and is opposed by environmentalists, how will any sort of abundance ever be realized? How will Californians escape a future of rationed scarcity?

This isn’t merely a question for California. As goes California, so goes America. And barring global conflict too terrible to contemplate, as goes America, so goes the world. The Lords of Scarcity will rule the world, coopting their counterparts in other nations, and a new era of feudalism will descend on humanity.

It might not be so bad. Vertical farming and cultivated meat will ensure that nobody starves. New social mores that stigmatize pregnancy as a crime against the planet, combined with a hedonistic culture that condemns traditional families, will result in a diminishing, aging global population. Androids will become caregivers and companions, frequently going into energy saving sleep mode as the apartment dwelling billions, reduced to existence in a handful of megacities, strap on their VR goggles and inhabit the thriving metaverse. Prescription drugs will pacify, palliate, and at the appropriate time, euthanize the old and infirm. Oligarchs will rule the world, machines will produce goods, algorithms will regulate information, and the vast majority of humans will have no idea what they’re missing. The planet’s ecosystems will thrive.

That’s an extreme scenario, and perhaps a cynical portrayal, although we may plausibly imagine far worse. The other extreme scenario, currently marketed by virtually every established institution in the Western World as factual and beyond debate, is that humanity must decarbonize and lower its environmental footprint or the planet will soon become uninhabitable. And based on California’s current politics of scarcity, the inescapable consequence of that premise is that a middle class lifestyle is unsustainable. One must either endure rationed scarcity – in a manner hopefully not as ghastly as imagined in the preceding paragraph – or life on earth will come to an end in a succession of cataclysmic climate catastrophes. That is the extreme narrative that we threatened with our initiative. But ideas without agency is like a head with no body, and agency requires power, and power requires money.

Maybe there’s a civic minded and contrarian billionaire who will spend $5 to $10 million to qualify an initiative to create water abundance in California, then spend another $20 to $50 million to convince voters to approve it. We tried to find one. Without at least a few powerful financial players deciding to challenge the ideology and conventional wisdom used to justify current energy and water policies and use their resources to fight for policies that instead nurture abundance, the Lords of Scarcity are going to win the war. In the meantime it is worthwhile to examine the assertion that middle class lifestyles are unsustainable. Even though it must be challenged, the argument is not unfounded.

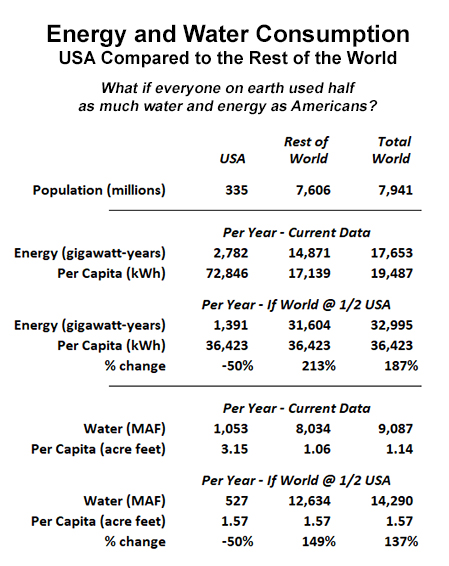

The next chart illustrates a stark truth about middle class lifestyles as enjoyed in America. If everyone, including Americans, consumed roughly half as much energy as Americans consumed per capita in 2020, global energy production would need to increase by 87 percent. Applying that same criteria to water would require fresh water availability in the world to increase by 37 percent.

The data on energy is gathered from the authoritative BP Statistical Review of Global Energy and is updated through 2020. The data on water relies on a 2012 study “The Water Footprint of Humanity” conducted by researchers in the Netherlands and cited later that year in Scientific American.

The energy data is fairly straightforward, although BP’s latest energy mega-unit of choice, “exajoules,” has been converted to gigawatt-years in deference to the electric age which, depending on who you ask, is either dawning with enlightened splendor, or being thrust upon us with no regard to efficacy or necessity. For a more thorough discussion of units of energy, refer to the earlier installment “Fighting Scope Insensitivity,” or, put another way, “Numbers Don’t Lie.” That installment offers plenty of details, but for the current discussion, only the proportions matter.

The data on water is anything but straightforward, and not merely because the mega-units were converted from cubic kilometers to million acre feet, but because a nation’s higher than average per capita “water use” doesn’t automatically equate to water waste. A nation with high per capita water use may have a lot of irrigated farmland, and export a lot of agricultural products. The 2012 study found that 92 percent of the global water footprint was for farming.

Even taking into account some limitations in the available data, anyone fighting for abundance must nonetheless confront an inescapable fact: Every American on average uses four times as much energy as people in the rest of the world, and they use three times as much water. Furthermore, if anything, the per capita water use for Americans is understated. Nuances can alter the implications of fractional differences, but they cannot explain away multiples of three or four times. Can abundance for everyone be achieved without destroying the planet?

There are several factors that have to be taken into account to answer this question. Perhaps to begin, here are some premises to introduce as worthy of vigorous debate, since to defend each of them would go well beyond the scope of a book dealing with water policy in California. So for better or for worse, they are:

- Reserves of fossil fuel – coal, oil, and natural gas – exist in sufficient abundance for global energy production to double within the next few decades, and last for at least another century. Indisputable data to support this claim can be found in the BP report.

- Emerging nations of the world are not going to abandon using fossil fuel until renewable energy is demonstrably cheaper and available at the scale they need to develop their economies.

- Renewable energy technologies have not demonstrated they have a cradle-to-grave ecological footprint that is significantly more benign than clean fossil fuel, and the raw materials currently required for their manufacture and operation may actually be more finite than fossil fuel.

- Abundant and affordable energy is highly correlated with, if not a prerequisite for, broad individual prosperity, female literacy and emancipation, urbanization, and lower birth rates.

- Lower birth rates and urbanization both lead to less pressure on wilderness habitats, agricultural land, and overall demands on natural resources. This is already happening in most of the world.

- Emerging energy technologies include fusion power, advanced fission reactors that reuse fuel, factory farmed biofuel, satellite solar power stations, clean hydrogen stripped from fossil fuel or generated from electrolysis, direct synthesis of carbon-based fuel from the atmosphere, and plenty more that we cannot yet imagine.

- Abundant energy translates directly into abundant water.

It’s important to emphasize that none of the preceding statements offered any challenge to the prevailing theories of CO2 induced climate change. But the sum of these statements amounts to a recipe – and a moral argument – for creating energy and water abundance for all the nations of the world. Adapting to climate change in California via rationing of energy, water and land, which is precisely what we are doing, will not influence the actions of the demographic heavyweights of the world, China, India, Indonesia, Pakistan, Brazil, Nigeria, or any other nation that aspires to elevate their citizens to the lifestyle enjoyed by Californians.

Moreover, exporting our policies in the form of international agreements and foreign investment strategies that effectively impose rationing of energy, which is exactly what America is doing today, will perpetuate poverty in those nations. In turn this will defer the voluntary population stabilization that accompanies prosperity, replacing it either with coercive restrictions on childbearing, or Malthusian famines caused by the politics of scarcity. Needless to say, it will also drive these nations to seek resources and financing from aspiring superpower rivals to the U.S.

What California’s policies are currently accomplishing runs contrary to the finest ideals of this state, exemplified from the earliest days of the modern era but especially now, as our technology elites introduce one pathbreaking innovation after another. Scarcity of water and energy, which translates to scarcity of housing and food and good jobs, is the precise opposite of what California ought to stand for, and it is an entirely avoidable condition.

California is blessed with almost every natural resource necessary for a modern civilization to thrive. So why aren’t California’s legislators passing laws to nurture prosperity and abundance in all things, only starting with water and energy.

Why has California’s logging and milling industry been regulated nearly into oblivion? Lumber has become prohibitively expensive in a state that as recently as 1990 harvested over six billion board feet a year of timber and now only harvests one quarter as much.

Why is California importing fertilizer for its eight million acres of irrigated farmland, when plentiful existing resources can be extracted right here to produce it? Why isn’t California trying to keep all of its farmland in production during this time of global food insecurity?

Why is California phasing out natural gas when it is the cleanest fossil fuel?

Why is California banning the internal combustion engine, when alternative combustible transportation fuels including hydrogen, natural gas, factory farmed biofuel, and carbon fuel extracted from the atmosphere are all possible ways to power advanced hybrid vehicles?

Why is California making it almost impossible to build houses on open land when the state is only five percent urbanized?

Why is California shutting down Diablo Canyon’s two reactors, instead of building the plant to its original six reactor design?

All of these policies are causing harm to ordinary Californians. As previously discussed, the idea that California, much less the world, can replace and then increase its total energy production with wind, solar, geothermal, and tidal power systems is ludicrous. California should be pursuing an all-of-the-above strategy with energy and water, using the cleanest and most efficient technologies we can come up with.

Replacing the destructive policies of scarcity with policies that nurture abundance would set an example to the world, and allow Californians to export leading edge products and technologies that appropriately address an insatiable, wholly justified demand – that everyone in the world achieve the standard of living that we take for granted.

That is the abundance choice.

***

Edward Ring is a contributing editor and senior fellow with the California Policy Center.