The Abundance Choice – Part 9: Can Reservoirs be Part of the Solution?

Editor’s note: This is the ninth article in a series on California’s water crisis. You can read the entire series including recent updates in his new book “The Abundance Choice, Our Fight for More Water in California.”

In May 1957, Harvey Banks, then director of the California Department of Water Resources, submitted “The California Water Plan” to the governor and state legislature. On page 14 of part one of this comprehensive document, Table 3 depicts what Banks and his team determined to be the “Estimated Present and Probable Ultimate Mean Seasonal Water Requirements.” The scale of their ultimate expectations reveals the magnitude of the challenge they had accepted.

At the time, the estimated statewide water requirements were 19.0 million acre-feet (MAF) per year for agriculture, which they estimated would ultimately peak at more than double that amount, 41.1 MAF/year. The total urban and miscellaneous use per year at the time was 2.0 MAF/year, which they estimated would eventually quintuple to 10.0 MAF/year. In all, California’s mid-century water planners intended to build infrastructure capable of delivering to farms and cities 51.1 million acre-feet per year.

This is a fascinating statistic, because this ultimate goal, set 65 years ago, easily fulfills the goal anyone might set who wishes to realize water abundance in California today. As we have seen, the average total water use in California in recent years for farms and cities was 41.6 million acre feet per year, well short of the 51.1 MAF goal set by Harvey Banks and his team back in 1957.

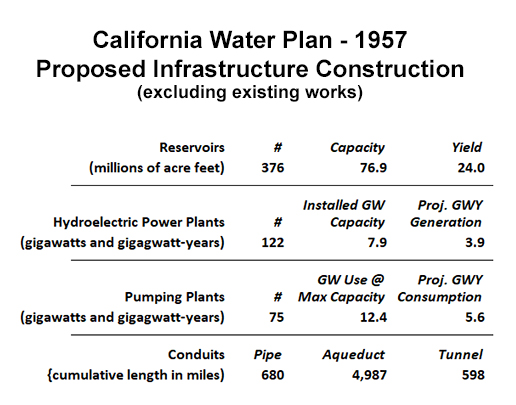

An examination of what they intended to build in order to accomplish this objective back then, compared to how it could be possible today, can uncover encouraging insights. To view this grand conception, refer to Table 30 on page 212 (ref. part two) of the original Water Plan, “Summary of Features, Accomplishments, and Costs of Physical Works Under the California Water Plan.” Or, for a summary of this summary, refer to the following table.

The 1957 Water Plan called for construction of 376 new reservoirs to be in addition to those already built. These new reservoirs were planned to add 76.9 million acre feet of new storage capacity with an average annual yield of 24.0 million acre feet. The other primary element of the 1957 Water Plan was to rely on interbasin transfers via an astonishing array of new conduits. These included 4,987 miles of canals, 680 miles of pipe, and 598 miles of tunnels.

The Energy and Water Nexus

The attentive reader will note that gigawatt-years is referenced on the summary chart above, instead of “millions of kilowatt-hours,” which appears on the source document. This unit of energy, gigawatt-years, is an underutilized but very useful point of reference. Its utility comes into focus when anyone attempts to determine the yield of an energy project. It makes it very easy to compare capacity in gigawatts (or megawatts), which is a common term used to report how much energy flow can be produced or consumed by a project when running at maximum output, to how much of that capacity is actually used (or produced) by a project over a period of time.

In the above examples, it can be seen that the new hydroelectric dams included in the 1957 Water Plan could have collectively generated an electricity flow of 7.9 gigawatts if all of the reservoirs had sufficient water to spin all the turbines, all the time, in all of the power houses. But given the amount of projected rainfall and timing of releases from these dams, the planners expected them to annually produce only 3.9 gigawatt-years of energy.

By normalizing these two measurements – flow of energy, and units of energy – to gigawatts, it is easy to see that the planners expected a yield of 49 percent (3.9/7.9). In their report, the planners projected a yield of 33,767 million kilowatt-hours, rendering it impossible for anyone viewing that table to intuitively assess the yield of these planned projects. One gigawatt-year is 8,766 million kilowatt-hours. Do that in your head.

If the goal of public policy discussions is to come up with rational public policies, the choice of units matters. For example, when viewing “nameplate capacity” on solar or wind installations, the amounts are typically reported in megawatts, and the yields are then reported in megawatt-hours. Without a calculator, this offers no insight into the yield of these devices. But when a solar or wind farm is installed with a reported output capacity of, for example, 500 megawatts, and the projected annual energy production is reported at 100 megawatt-years, one knows immediately that the yield is 20 percent (100/500). One megawatt-year is 8,766 megawatt-hours (365.25 x 24). More on this later.

In specific reference to California’s water infrastructure, normalizing these variables also makes it easy to compare the estimated annual energy yield from the planned hydroelectric dams (3.9 gigawatt-years), and the estimated annual energy consumption of the planned pumps (5.6 gigawatt-years), to the total electrical generation in California. In 2018, according to data compiled by the Lawrence Livermore Laboratory, California generated 1,700 trillion BTUs of electric power, which equates to 57 gigawatt-years (1,000 trillion BTUs equals 33.4 gigawatt-years). This is interesting. Had the 1957 Water Plan been fully implemented, today those new pumps would be consuming an amount equal to 10 percent of California’s entire electricity consumption today (5.6/57), offset by planned hydroelectric generating capacity that may have given back an amount equal to 8 percent of California’s current electricity consumption (3.9/57).

If the reader will forgive a digression into the nexus between water reservoirs and renewable energy, by normalizing these units, it’s easy to imagine the electricity storage potential of these planned hydroelectric plants if they’d all been not only constructed, but constructed with reversible turbines, making them able to pump water uphill from forebays into the reservoir during hours when peak solar power is hitting the grid. In one hour, 7.9 gigawatts (their planned capacity) of reversible hydroelectric dam turbines could store – at a pumping efficiency of 80 percent – 6.3 gigawatt-hours of surplus solar power, to be released back down through the turbines now switched back into generating mode during those peak hours when our electric utility PR departments nowadays instruct us to “power down.” There’s nothing fanciful about these speculations. San Luis Reservoir, which has reversible turbines, is already a big battery. So are most of the reservoirs in Norway.

The Cost Then, The Cost Now

An unforgettable detail of the 1957 Water Plan is their projected cost for all of this, $11.8 billion. For all of it. In 2022 dollars, $11.8 billion is worth $113.8 billion. This too, is encouraging. When the Office of Legislative Analyst estimated how much it would cost for our initiative to fund capital projects that would result in supplying an additional five million acre feet of water per year, they wrote the following: “We estimate the cost of implementing new projects to develop 5 million acre-feet of new, reliable, statewide annual water supply will be several tens of billions of dollars, potentially totaling more than $100 billion.”

Californians were prepared to spend that much back then. For this century, we should be willing to do the same. With everything we’ve learned, we can do it in a manner that is far more sustainable in all ways – financially and environmentally.

When reviewing this 1957 plan, what ought to motivate us is that what we already have built today and can envision for the future is a system that can achieve these original goals in large part through innovations that didn’t exist back then. We can construct off-stream reservoirs like the proposed Sites project. We can limit new in-stream construction to expansion of existing dams such as Lake Shasta, or construction of new in-stream dams upstream from existing dams such as in the case of the proposed Temperance Flat project. Better yet, we can capture runoff into spreading basins where it will percolate into underground aquifers for storage and recovery, we can recycle urban wastewater, and we can desalinate brackish water and seawater.

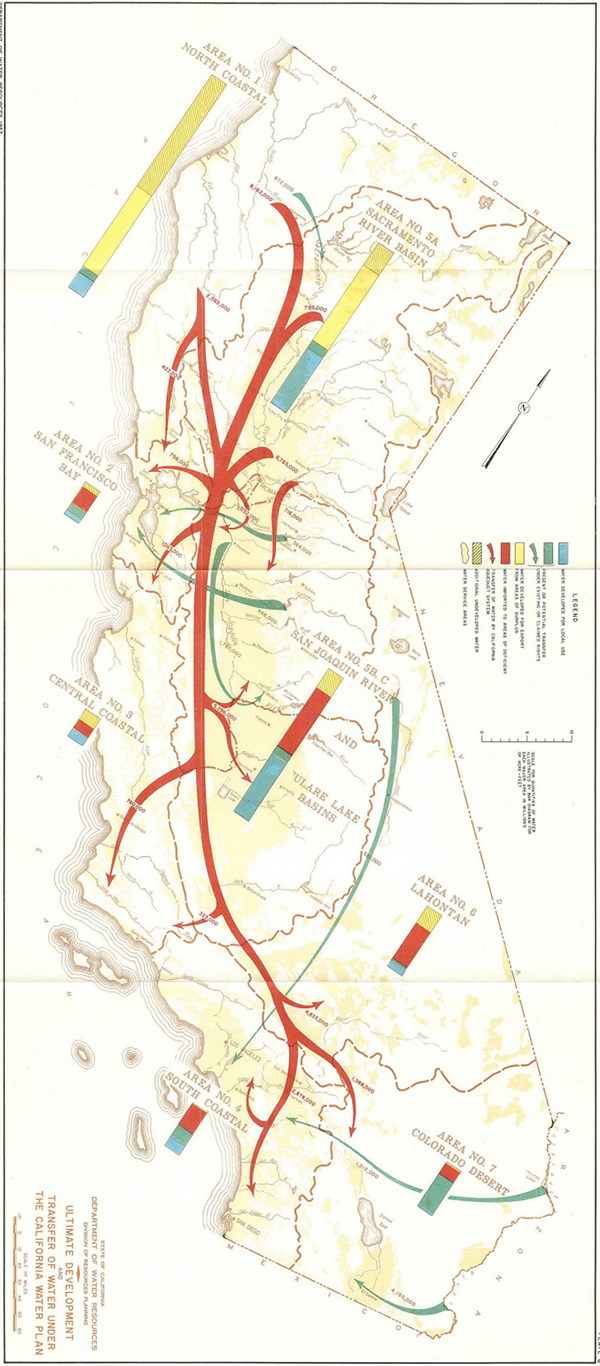

By developing these new types of projects, we don’t have to adhere to the original scope of the 1957 Water Plan. As indicated by the map taken from page 149 of part two of the 1957 Water Plan, it was an ambitious plan, and much of it was implemented. The California Aqueduct and its network of reservoirs and secondary conveyances is the most notable among the proposed projects which were built. But as the map from that era shows, significant portions of the plan were never finished. For example, diversions south from the Klamath and Eel rivers were not fully implemented, and the Auburn Dam on the north fork of the American River was never built. It is the water that might have been available from these planned diversions, never realized, that can instead be fulfilled via urban wastewater reuse, runoff capture into off-stream reservoirs and aquifers, and desalination.

Reservoirs In-Stream and Off-Stream

Which brings us to the most controversial of the eligible project categories we defined in the initiative, surface storage. We must immediately differentiate between in-stream reservoirs and off-stream reservoirs. They have distinct attributes. In-stream reservoirs in general are considered far more disruptive. To note just a few of the most obvious problems with in-stream reservoirs, the dam constitutes an immovable blockade of a naturally flowing river, the canyons behind the dam are inundated, and fish swimming upstream cannot reach their spawning grounds.

There are nonetheless arguments for some in-stream dams, particularly if they’ve already been built. The Shasta Dam is the prime example, because of its unique depth. With a maximum depth that is over 500 feet, the snowmelt that fills Lake Shasta stays cool and can be released year-round in order to manage the water temperature in the Sacramento River. By carefully timing these releases, Salmon eggs which require colder upstream temperatures can survive, while at different times of year, young Sturgeon can benefit from the warmer water they require to survive in the lower river.

If the Shasta Dam were increased in height by just 18.5 feet, at an estimated cost of $1.4 billion, it would add over 600,000 acre feet to its already impressive 4.5 million acre foot storage capacity. This construction price, $2,000 per acre foot of storage, is extremely low compared to most other options. But despite being cost-effective, and despite the need for more cold water storage to help manage ecosystems downstream, environmentalist opposition to raising the Shasta Dam has kept the project at a standstill for years. Among the many environmentalist objections is the fact that in years the dam collects enough runoff to be filled to capacity, the expanded lake will inundate a few additional miles of the McCloud River, which has raised concerns among Native Americans and fishermen. But these concerns must be balanced against the benefits downstream. And at such a relatively affordable cost, surely there could be generous funds for mitigation projects that might help offset the impact on the McCloud River.

While environmental impact is the primary source of objections to water infrastructure, there is also a familiar and understandable concern from the people living in the areas impacted. In extreme cases they are forced through eminent domain to relocate their homes and businesses. Frequently they see the land and communities they’ve known all their lives completely transformed. This is never easy. It is never trivial. But it must be understood as a common thread of human history, past, present, and everywhere. First there were Native Americans, then there were the Spanish, then the Mexicans, then the Americans. California’s population in 1848 was approximately 150,000 Native Americans, approximately 6,500 people of either Spanish or Mexican descent, and only an estimated 800 American immigrants of non Hispanic European descent. Today, less than two centuries later, 40 million people live in California. That’s a lot of displacement.

Someone living near the McCloud River, upstream from Lake Shasta, may live in an area that has been bypassed so far by the footprint of civilization. But their situation is no different from anyone, ever, who has been displaced or disrupted by the tides of history. What about someone who lived in the Santa Clara Valley back in 1957, the year when Harold Banks turned in his California Water Plan? In the decades since then its name has been changed to the Silicon Valley, and from all over the world people came, by the millions, to live there. Where less than one lifetime ago, there were blossoms in the endless orchards every spring, now there is a megapolis. This is the story of California. An endless, burgeoning dreamland, a magnet for the world. Without water, growth stops, prosperity stops, and the dream becomes a nightmare. That is the tradeoff. That is another context from which to view the controversy over the McCloud River.

The unavoidable truth of water infrastructure, along with all other infrastructure, is that it will change the earth. We can handle this with all the money and technology and learning we’ve acquired in the 65 years since 1957, when the engineering challenge was the only paramount concern. But even when designing into new infrastructure the most enlightened and advanced mitigating features, civilization has a footprint. Applying the latest techniques to construct fish ladders and manage sediment are ways to mitigate the impact of in-stream dams. There isn’t any state or nation, anywhere, that can do a better job than Californians at mitigating the impact of our infrastructure on the environment. But it is not our obligation to impoverish ourselves in the process, and by failing to meet this challenge we also deny ourselves the opportunity to set an example to the rest of the world, which for the most part is populated by people who have had quite enough of impoverishment.

Which brings us to off-stream reservoirs, which most would agree are a slightly less transgressive form of water infrastructure. Instead of blocking a river, off-stream reservoirs in California are designed to occupy an expansive, arid valley, one that typically must be situated either near a large river or close to an aqueduct. The San Luis Reservoir, located just south of the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta and close to the California Aqueduct, is California’s best example of an off-stream reservoir.

Built in just four years and operational by 1967, the San Luis Dam cost $3.1 billion in 2022 dollars. This price included the pumps to lift water over the 380 foot dam, and the forebays below the dam where water is diverted from the California Aqueduct. The pumping plant has eight reversible turbines that can either consume or generate 424 megawatts of electricity, depending on whether they are pumping water from the forebay into the dam, or releasing water from the dam back into the forebay. By filling the dam from the forebay during periods of surplus electricity, and then generating power by releasing that water back down to the forebay during periods of peak demand and high electricity prices, the San Luis Dam is capable of storing intermittent renewable energy. As previously noted, the pump storage capacity of off-stream reservoirs is a compelling additional argument in favor of their construction, as California’s state legislature continues to rush headlong into an all electric, renewable energy future.

If San Luis Reservoir is a perfect example of what off-stream reservoirs can offer, the proposed Sites Reservoir Project is pretty good. In its original concept, it would have been the glorious twin to San Luis, situated in the hills just north of the Delta and west of the Sacramento River. Like San Luis, the Sites Reservoir was originally conceived to have nearly 2.0 million acre feet of storage capacity. Also, just like San Luis, Site’s original design included pump storage to harvest surplus electricity. But that was the dream.

As it is today, the latest Sites project proposal is still impressive. With a planned a storage capacity of 1.5 million acre feet it will be the eighth largest reservoir in California. Unfortunately it will not have electrical pump-storage. According to officials with the Sites project, downsizing the dam and eliminating pump storage were the result of “affordability, permitting and constructability challenges.” In any case, where is Sites? Its construction was approved by voters eight years ago.

Paralytic Bureaucracies and Endless Litigation

The answer to this question is the paralyzing bureaucratic inertia and perpetual blocking lawsuits that have stopped all major water projects in California for the past thirty years. Our initiative was written specifically to address affordability and permitting challenges – leaving constructability to the engineers. But back in 2020 Jerry Brown (no, not the ex-Governor), the executive director of the Sites Project, posted a video on YouTube to answer this question: What’s taking so long to build the Sites Reservoir Project? Here’s his answer:

“My experience is that for every one year of construction you have about three years for permitting, so for us we have about a seven year construction period, that would mean we’d have about a twenty year time frame for the total project. Our JPA started in 2010, we’re estimated to be completed in 2030, so actually, we’re pretty much on schedule.”

This comment may accurately reflect the reality of how long infrastructure projects take in California today, but it begs the question: Does this mean every major water infrastructure project that hasn’t yet formed a JPA will not be operating until 2042 or later? And how certain is Jerry Brown that Sites will be operating by 2030? What is going to prevent environmentalist lawsuits from continuing for another few decades? And if our state legislature is absolutely determined to power the state’s grid with intermittent wind and solar energy, why was the pump storage feature removed from the final Sites design?

In the February 2021 document “Sites Reservoir Project – Preliminary Project Description,” the introductory section describes how back in 1995 the CALFED Bay-Delta Program “identified 52 potential surface storage locations and retained 12 reservoir locations statewide for further study.” All twelve were off-stream reservoirs. They then narrowed the candidates to four: “Red Bank (Dippingvat and Schoenfield Reservoirs), Newville Reservoir, Colusa Reservoir, and Sites Reservoir.” Sites was chosen as the most feasible project. But why isn’t this study being dusted off and revisited? What about these other potential locations for more surface storage? Why not at least construct the other three finalists? Isn’t California entering a climate era of less snow, and more irregular but torrential downpours?

The reason for asking this question isn’t to indulge a penchant for highlighting projects that environmentalists find the most transgressive. First of all because off-stream reservoirs aren’t nearly as problematic as in-stream reservoirs. The reason to question why more surface storage isn’t being seriously considered as part of a comprehensive plan to create water abundance in normal years, and water security in years of drought or civil disasters, is because surface storage accomplishes goals that are very hard to otherwise fulfill. Reservoirs with pump storage are the most cost-effective way to absorb and then release surplus electricity. They are also the only way to capture a significant volume of storm runoff, which can only then be released slowly from these reservoirs into percolation basins and injection wells for aquifer recharge.

Imagine if back in the 1930s through the 1960s, every major water infrastructure project took three years of planning for every year of construction. Imagine if back then, every major water infrastructure project were tied up in litigation for decades, with the legal fees, settlement costs, and delays adding tens of billions to project costs? Would anything have been built?

Maybe every major water infrastructure project wasn’t ideal. Maybe history will someday applaud the fact that back in the 1970s the state legislature pushed the pause button, and never completed the original California Water Plan conceived back in 1957. But without the reservoirs that we did build, and the aqueducts and pumping plants that accompanied those reservoirs, California would not be home to one of the most iconic, inspiring civilizations the world has ever known.

The environmentalists who oppose Sites, and every other reservoir, even those situated off-stream that can also store surplus electricity, should look to their own backyards. They should consider San Francisco’s relatively drought-proof source of pristine drinking water, Hetch Hetchy, an in-stream abomination that throttled the wild Tuolumne River, and inundated a valley equal in beauty and grandeur to Yosemite.

As Californians along with everyone else in the world navigate the tempestuous road ahead, this state needs an infrastructure with redundancy. Conservation and ultra-efficient water use is analogous to just-in-time inventory. With only a small disruption to the supply chain that has already wrung every drop of efficiency into it, crops and people can die of thirst. An all-of-the-above solution to water scarcity in California is a prudent strategy, and reservoirs are a part of that equation.

There is a moderate path forward. It requires trade-offs. For example, a few of the obvious reservoir candidates for removal, starting with Hetch Hetchy, could be demolished and those ecosystems restored to a wild state. But at the same time, off-stream surface storage reservoirs like Sites are an essential part of California’s recipe for water security, as is raising the height of some already existing in-stream dams such as Shasta. Pursuing a strategy of water abundance permits all of these options. By adding more reservoir storage than we remove, dreams like completely restoring the Tuolumne watershed can become reality.

***

Edward Ring is a contributing editor and senior fellow with the California Policy Center.