Time to Restructure Failing BART System

Of all the public agencies facing financial challenges as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, public transit has taken the biggest initial hit. The reasons for this are obvious: when there’s a lockdown and businesses are closed, commuters stay home. And of those still fortunate enough to have places to go, few want to board busses and trains where they risk heightened exposure to contagions.

Northern California’s biggest transit system is the Bay Area Rapid Transit District, commonly referred to as BART, with operating expenses of nearly $1.0 billion per year. In good years, operating revenues – primarily fares and parking fees – never covered more than around 75 percent of operating costs. But that was back in 2016, when ridership peaked, at around 435,000 per weekday, whereas pre-COVID ridership in early 2020 was running around 405,000 per day. Weekend ridership had been dropping at a higher pace than weekday commuting because of board policies that tolerate homelessness, open use of hard drugs, panhandling and petty theft on the trains.

In addition, over the past four years, the BART board of directors has been giving away an increasing array of discounts at the same time as operating costs have steadily increased. There has also been increasing tolerance on the part of the board for fare evasion which lowers revenues by, depending on which expert you ask, between $25 and $50 million per year.

In April 2020, at the height of the pandemic shutdown, BART ridership fell to 6 percent of what would have been normal for that month. Today, ridership has only rebounded to around 13 percent of normal. Even the most optimistic expectations for the fiscal year ending 6/30/2021 only estimate ridership to rebound to around 35 percent of normal.

Even without COVID as an obstacle, will BART ridership ever recover from its steady decline? How many of the major San Francisco employers still attract commuters, when, for example, Schwab, Wells Fargo, and PG&E are all moving operations out of the city, and others intend to dramatically scale back in-person office work?

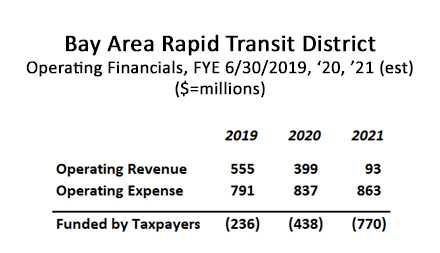

The financial implications of this implosion in ridership are shown on the following chart, which draws from publicly disclosed information. It doesn’t take a financial wizard to see the trend. Plummeting revenues, rising costs, skyrocketing deficits.

What BART faces in its current fiscal year, based on what may be optimistic ridership expectations, is a system that can only pay for 11 percent of its operating costs through operating revenues. This isn’t nearly enough to allow the normal state and local tax subsidies to cover the difference. To cover this shortfall, BART, like most public agencies in California, is looking for federal bailout funds. They have already received $377 million of federal subsidies, and they’re going to need at least another $230 million just to get through the next 18 months. But what if BART experiences a sustained drop in ridership? The assumptions that governed planning and management of the BART system have fundamentally changed, probably forever.

BART’s Financial Challenges Must be Faced

The BART system has always relied on subsidies to fund their operations. That is considered normal for public transit agencies. But these subsidies have enabled BART management to avoid making tough choices to improve the efficiency of their operation. And the actual cost for BART is not only based on their operating budget that currently sits at around $850 million per year, but its annual capital budget that always exceeds $1.0 billion per year. And 95 percent of BART’s annual capital budget typically comes from taxpayers.

As with most public agencies, pay and benefits are the most significant cost variable. BART’s direct employee costs including benefits during 2019, based on data reported to the State Controller, were $623 million, including over $72 million in overtime. Based on information provided by BART to the State Controller, in 2019, the average pay and benefits paid to a full time BART employee was $163,000, not including payments necessary to reduce the unfunded pension liability.

Making up for years of inadequate pension fund contributions is an expensive undertaking. As of 6/30/2019 (the most recent data available for BART’s safety and miscellaneous employees), BART’s unfunded pension liability stood at $833 million dollars. CalPERS’ own data projects an unfunded payment from BART in the 2020-21 fiscal year of $59 million. Add that to the direct employee pay and benefit costs to get a more accurate estimate of personnel costs.

It would take more than a casual look at these averages to fully understand where there might be room for, at the very least, a freeze in pay and benefit increases of any kind. This sort of analysis could be performed with most of the BART positions, by comparing them to what, for example, people with similar job descriptions earn while working for Amtrak, or other railroad operations in California. If there is to be any appropriate time for making this sort of tough analysis, now would certainly qualify.

BART Oversight and Management is Lacking

It is difficult to ascertain who exactly runs BART. The board of directors consists of 9 part-time positions. The individuals occupying these elected positions contend with low voter awareness, and hence are often dependent on funding from the unions representing BART employees to pay for their political campaigns. In this current election season, both the SEIU and AFSCME, representing bargaining units at BART, have contributed to reelect their favored candidates.

When examining the posted biographies of BART’s current board of directors, it is fair to wonder what qualifies them to manage a transit organization with a combined operating and capital budget that exceeds $2.0 billion per year. Without dwelling on the publicly available details, one must wonder why board members whose primary career experiences were as community organizers, homeless activists, racial justice advocates, open space preservationists, cycling aficionados, and similar non-financial pursuits, are qualified to negotiate with the unions that funded their political campaigns. There is only one former CPA on the nine-member board, hardly constituting a majority.

Meanwhile, the actual governing majority of board members are deferring discussions as to how to fill more projected deficits until after the November 3 election. But when will BART’s board members step up and address systemic management failures? The COVID-19 shutdown may have brought the consequences of mismanagement to an early crisis, but even if there’s a bailout and reopening, the crisis will persist. Without major restructuring, BART is not sustainable. For example:

- The board needs to right-size the services and the top management overhead.

- The system needs to divest of non-transit activity such as developing low-income housing on BART property.

- They need to prioritize their transit projects and rethink their level of involvement in major proposed expansion projects.

- They need to renegotiate the work rules that have enabled BART employees to manipulate their schedules to maximize overtime.

Three of the public employee union contracts expire in June 2021. Negotiations to renew these contracts are already underway. If BART’s board of directors is serious about restoring any sort of financial sustainability to their system, all contract provisions should be subject to negotiation.

In the current contract negotiations, if BART had a financially literate board of directors that properly understood that their job required them to prioritize the interests of fare paying riders and taxpayers, union rumblings of a strike would be met by the respectful suggestion to “go ahead.” With BART ridership at a small fraction of normal, and a new world dawning on the other side of the COVID pandemic, now would be a perfect time to shut BART down and redesign the entire system.

This article originally appeared on the website California Globe.