Valley Transportation Authority: A textbook case of “Special Interests” prevailing over public good

In the heart of Silicon Valley, where innovation is supposed to reign supreme, the Valley Transportation Authority (VTA) has become a textbook example of government waste, mismanagement, and the creep of crony politics that prioritize insiders over the public good.

The agency’s latest draft budget for Fiscal Year 2027 (FY27) projects a staggering $14.9 million deficit, ballooning from a modest $868,000 shortfall in FY26. This is not a sudden calamity but the predictable outcome of years of declining ridership, unchecked labor cost increases, and a reliance on increased tax incidence on gullible taxpayers.

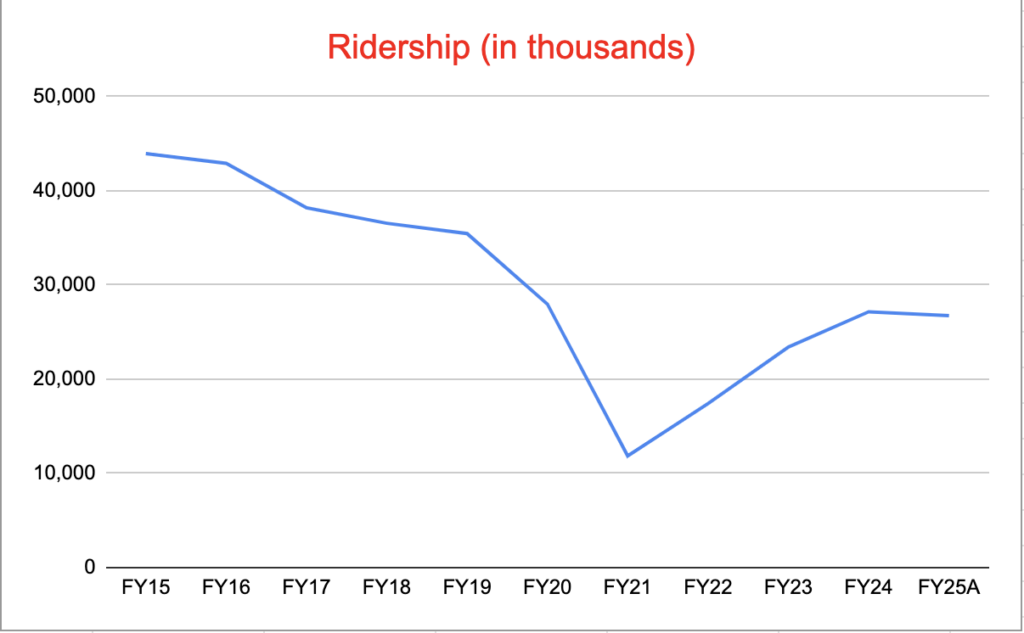

Let’s start with ridership, the lifeblood of any transit agency. VTA’s ridership peaked at 43.944 million in FY15, long before COVID-19. It had already fallen over 19 percent by FY19. In FY25, ridership is projected to be 40 percent below that high-water mark of FY15, a decline that began well before the pandemic and has only worsened. Also, FY25 ridership is down from FY24, casting serious doubt on VTA’s rosy projection of a nearly 15 percent ridership increase in FY26. What fuels this optimism? Certainly not data or reality. The agency’s own history shows a steady erosion of public trust and utility, with ridership numbers reflecting a service that fewer and fewer people find worth using.

Source: VTA, https://www.vta.org/business-center/financial-investor-information

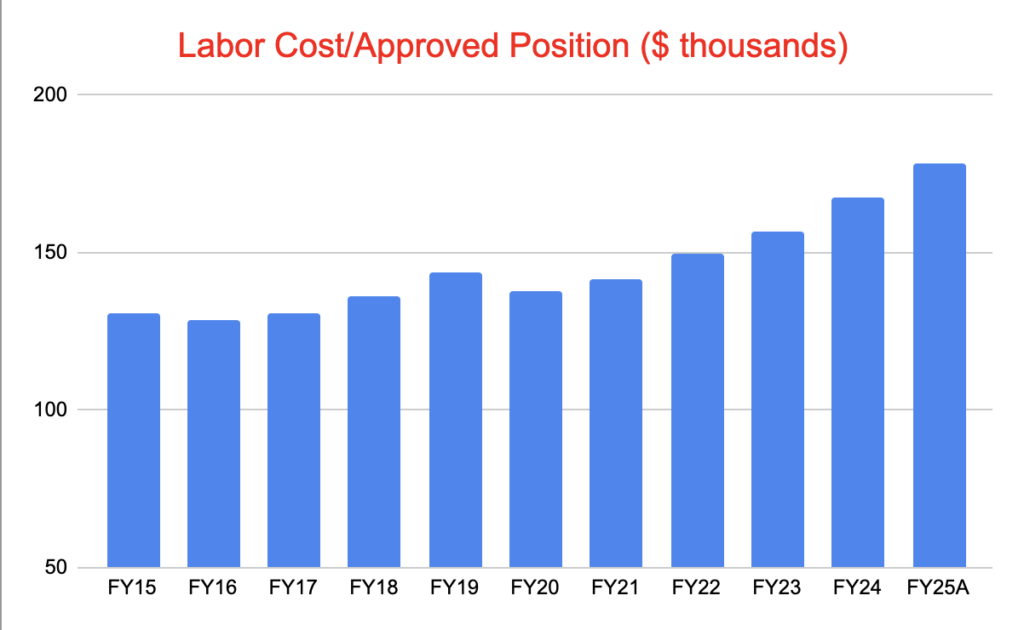

While ridership plummets, the only thing soaring at VTA is labor costs. Since FY15, employee expenses have surged by 47 percent from $289 million to $427 million, and the agency’s workforce has grown by 8 percent, despite serving 40 percent fewer passengers. The VTA’s primary revenue source — local sales taxes, which account for over 80 percent of its income — has been a boon thanks to Santa Clara County’s tech-driven economy. But rather than investing in better service or infrastructure to reverse ridership declines, nearly all of this revenue has been funneled into higher salaries and more employees. Picture this: FY25 has seen a $149 million increase in sales tax revenue (including the 2016 Measure B) over FY15. Over the same period, increase in labor costs has been $137.5 million, accounting for almost the entire increase in sales tax revenue.

Source: VTA, https://www.vta.org/business-center/financial-investor-information

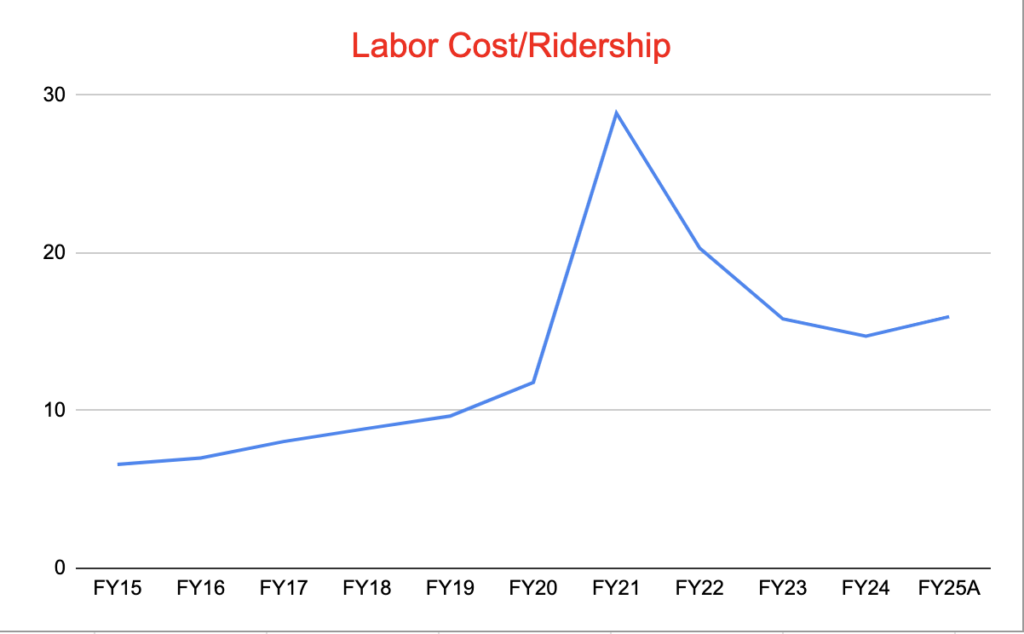

Labor cost per rider trip has jumped 2.5 times from $6.5 in FY15 to $16 in FY25. County residents are now paying almost 146 percent more in labor expenses to put a single passenger on a VTA vehicle, even though the overall Consumer Price Index (used to track general prices over time) has risen just by a third over the same time frame. This means tax dollars don’t go as far as they used to, and signals deep inefficiencies the agency needs to tackle.

Source: VTA, https://www.vta.org/business-center/financial-investor-information

Santa Clara County voters approved Measure B in 2016, a half-cent sales tax increase sold as a way to “enhance transit” and fund critical infrastructure like the BART Silicon Valley extension. This measure, passed with 72 percent support, was supposed to be a game-changer, leveraging local revenue to secure regional and federal funds. Instead, it’s become another burden on taxpayers, with funds largely absorbed by VTA’s ever-growing labor costs and payrolls instead of delivering the reliable, high-quality transit system voters were promised.

For the price of its bloated labor budget, VTA could have invested in practical solutions: more frequent bus routes, modernized light rail, or transit-oriented development to generate sustainable revenue. Instead, the agency clings to costly megaprojects like the BART extension, which promise little ridership gain for billions in expenditure. A 2024 state audit highlighted the folly of VTA’s $653 million Eastridge light rail extension, projecting a mere 1.5 percent ridership increase by 2043, hardly a justification for $272 million per mile of track. These projects aren’t about serving the public; they are about perpetuating a cycle of spending that enriches connected interests while leaving riders with subpar service.

The recent strike by VTA staff, represented by the Amalgamated Transit Union Local 265, only underscores the agency’s dysfunctional priorities. In March 2025, VTA was forced to file a legal complaint against the union for breaching a “no-strike” clause, disrupting service and further eroding public confidence.

It’s a stark reminder of the entitled mindset that pervades public sector unions, who see taxpayer money as an endless well to tap.

VTA’s defenders might argue that maintaining service levels in the face of economic uncertainty is a victory. But preserving a broken system is no triumph. With ridership at 60 percent of peak levels, VTA’s refusal to confront its structural issues, from extremely low farebox recovery (just 5 percent) to runaway labor costs, ensures that deficits will grow and taxpayers will keep footing the bill.

The VTA’s budget woes are not an isolated case but a microcosm of a state where special interests, unions, government bureaucrats, and their political allies line their pockets while public services stay mediocre. This is the essence of California’s public sector dysfunction: a system where failure is rewarded, and taxpayers are left holding the bag. Santa Clara County deserves better.

Athan Joshi is a visiting research assistant for California Policy Center’s summer 2025 term.