Why is San Diego’s Pension Settlement Estimate So Much Money?

In 2012, San Diego voters approved Proposition B, a pension reform measure that replaced pensions for new hires with a 401K plan. Seven years later, this reform is likely to be completely unwound, because union attorneys successfully argued that the city did not “meet and confer” with the unions before putting the reform measure on the ballot for voter approval.

As reported two weeks ago, the U.S. Supreme Court refused to hear the city’s argument that San Diego’s mayor, who supported Prop. B, was exercising his right to free speech, and to force him to meet and confer with the unions prior to supporting Prop. B would have been a violation of that right.

The case was then returned to the original appellate court, which on March 25th ruled that the city must “meet and confer over the effects of the initiative and to pay the affected current and former employees represented by the Unions the difference, plus seven percent annual interest, between the compensation, including retirement benefits, the employees would have received before the initiative became effective and the compensation the employees received after the initiative became effective.”

This ruling raises more questions than it answers. For example, does this ruling definitely require the city to pay those employees affected by Prop. B? This is unclear, because the next sentence of the ruling seems to offer the city a way out, by stating:

“The City’s obligation to comply with the compensatory remedy extends until completion of the bargaining process …before placing a charter amendment on the ballot that is advanced by the City and affects employee pension benefits and and/or other negotiable subjects.”

In plain English, it appears the court has ordered the City of San Diego to meet and confer, then if an impasse is reached, to place an amended version of Prop. B in front of the voters. However, this raises another question – did the City of San Diego really put Prop. B on the ballot, while violating the meet and confer requirement?

The actual proponents of the measure, Steve Williams, TJ Zane, and April Boling, were private citizens. They put Prop. B on the ballot, and the funds used to qualify Prop. B and campaign for Prop. B were all privately sourced. While San Diego’s mayor supported Prop. B, he only did so after these private parties had announced their campaign. Prop. B would have been put before voters, and likely passed, with or without support from the mayor.

For this reason, if and when a settlement is reached between the City of San Diego and the unions, a lawsuit will be filed on behalf of the true proponents, arguing that there never was a “meet and confer” requirement, since the initiative originated outside of city hall. But how much money is really at stake?

While some of those close to the case maintain that estimating how much it would cost to “make whole” the employees affected by Prop. B is getting “into the weeds,” these might be very big weeds, or they may be insignificant weeds. Nobody seems to have any idea if these weeds are microscopic cilia or Sequoiadendron giganteum.

Why Do News Reports Estimate Such A Huge Potential Liability to the City of San Diego?

According to a report in the San Diego Union Tribune, “Estimates of the city’s costs have ranged from $20 million to $100 million based on a variety of factors, but a precise estimate isn’t possible without a comprehensive actuarial analysis.” That’s quite a range of estimates, with a huge number of gigantic variables affecting the calculation. Yet, the biggest question is, why are these estimates of the city’s costs so high? Three simple examples illustrate why this is a compelling question.

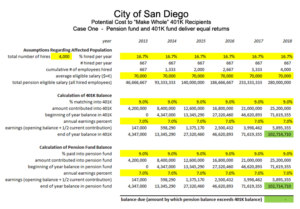

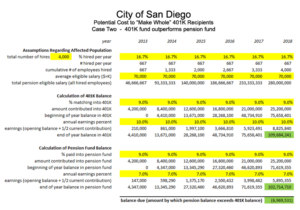

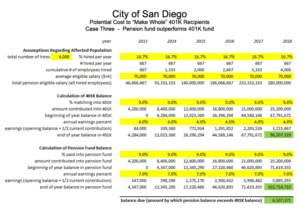

In all cases, the same basic assumptions apply. On the three charts below, these assumptions are highlighted in yellow. It is assumed that the 4,000 employees affected by Prop. B were hired over the past six years in equal increments, i.e., 667 new hires per year. It is assumed that their average 401K eligible (or pension eligible) salary is $70,000 per year. It is also assumed that the amount the city contributed into a 401K on behalf of these employees was the same as the amount they would have contributed into the pension fund. More on that later. For these examples, that contribution is assumed to be nine percent.

As can be seen in the first case, if you assume that the annual earnings percent for the 401K fund is equal to the amount earned by the pension fund, seven percent per year, than the amount by which the pension fund balance would exceed the 401K fund balance is zero. The next two cases show the financial impact if these earnings percentages differ.

As can be seen in the second case, below, if the 401K fund outperforms the pension fund, by earning ten percent per year compared to a fixed seven percent, which the pension fund uses as its long-term average annual return for actuarial purposes, then the impact of Prop. B on the affected employees is actually positive, with the City of San Diego in a position of having overcompensated these employees by giving them a 401K plan.

In the third case, it is assumed the pension fund, earning seven percent per year, has outperformed the 401K fund, which is only assumed to have earned four percent per year. Since it is typically an option for 401K plan participants to select a low risk investment option, for many of the 401K participants this may have occurred. But as can be seen on the chart below, even if every one of the 4,000 new employees selected this option, the city’s liability would only total around $6.5 million.

Reviewing these three cases, it begs the question: Where are analysts coming up with a “$20 to $100 million” estimate of potential costs to the City of San Diego to move these 4,000 employees from a 401K plan onto a pension plan, or goose their 401K plan to make it equal to the value of the pension benefits they would have accrued by now? Certain things can be ruled out.

For example, you can rule out the possibility that the pension eligible salary estimate of $70,000 is too low. Because even if it were much higher, say $100,000 on average, that would only increase the amount of the liability by 30 percent. Similarly, you can rule out the timing of these hires as a critical variable, because even if you hired two-thirds of them in the first three years, instead of only half of them in the first three years, you would only increase the liability in Case Three (pension fund outperforming 410K) from $6.5 million to $8.0 million.

This leaves two critical variables that must account for the high estimates for the city’s potential liability, the annual earnings percent, or the percent of salary paid into either the pension fund or the 401K plan. The annual earnings percent can be ruled out immediately, because while the pension fund experiences earnings that vary widely from year to year, they rely on a long-term average rate-of-return that rarely changes. When these earnings assumptions do change, they change very little. It would be interesting to see how one might argue that the extraordinary returns the pension fund may have realized during 2017, when the stock market exploded, would have to be taken into account, since only the long-term average rate-of-return assumption is relevant to actuarial valuations and determining contribution amounts. And in any case, 401K plans also saw their values explode in 2017, probably cancelling out that effect. This leaves only one variable for consideration – the percent paid into the pension fund – THE critical variable.

Here you can come up with extraordinary numbers indeed. For example the City of San Diego currently pays 72 percent of pension eligible payroll (SD CAFR, page 192) into their pension fund. If you plug that number into Case One, leaving every other assumption unchanged, the cost to “make whole” these 4,000 new hires affected by Prop. B is $719 million. Clearly, the entire substance of the “meet and confer” just mandated by the appellate court will focus on what this contribution should have been. And that’s worth a few more thoughts, because there’s a reason the contribution percentage is an outrageous 72 percent.

As reported two weeks ago, and as documented in the 2018 financial report for San Diego’s pension fund (SDCERS CAFR page 91), the city’s pension fund liabilities exceed its assets by $2.8 billion. This means that most of the payments the city is making to their pension fund is to catch up after falling so far behind. But should new employees have these catch up payments considered part of their pension benefit? This brings up interesting contradictions.

First of all, every new employee’s individual pension benefit is, theoretically, kept fully funded merely by making the so-called “normal contribution.” That is the amount that has to be invested in the pension fund in, for example, 2018, to earn interest over time so there will eventually be enough money to pay for the amount of future retirement benefit that was earned in 2018. How much are these “normal contributions” as a percent of payroll? Typically they are not very much, which is why the pension plans fell behind. They also fell behind, way behind, when pension benefits for City of San Diego employees were retroactively enhanced, back in the early 2000s. But is any of that the fault (or the benefit) of the new hires? Of course not.

There’s a lot of hypocrisy at work here. The higher the rate-of-return assumption, logically, the lower the normal contribution, since less money has to be contributed each year if you think that money is going to earn more in interest over time. Since public employees typically have to pay a share of their normal contribution via withholding, their unions have used their influence on the pension fund boards to keep that interest rate assumption higher than it might otherwise be. Another glaring, albeit abstruse hypocrisy is the fact that whenever watchdog organizations call attention to the lavish “total compensation” averages for public employees, amounts that are invariably elevated based on huge per employee “catch up” contributions to the pension funds, the union spokespeople counter with the argument that these catch up, or “unfunded contributions” shouldn’t be included. Fair enough. Then they should not be included in any settlement agreement, either.

This brings us to the final question: What is a reasonable “normal contribution” to San Diego’s pension plan for the 4,000 mostly miscellaneous employees (police were exempt) affected by Prop. B? Is nine percent per year sufficient? And if so, then why are we talking about a settlement estimate in the tens of millions, instead of mere millions?

* * *

Edward Ring is a co-founder of the California Policy Center and served as its first president.