Will Anything Good Come Out of the LAUSD Strike? Probably Not

As the teachers strike in Los Angeles entered its second week, it appeared that it would be over soon. Yesterday, online reports declared an agreement had been “hammered out,” with union members ratifying the deal late last night.

Union representatives have consistently stated that more pay is not the only reason they’re striking. That’s believable. The unions also desire to unionize charter schools, want smaller class sizes, and demand more hiring – for example, a full-time nurse at every elementary school. Nonetheless, all of this costs money.

Noriko Nakada, a LAUSD public school teacher, wrote a column in the December 18th edition of the UTLA “United Teacher” newspaper, entitled “People don’t strike for 6%; we strike for justice.” Considering each of those two phrases, one at a time, yields insights into what’s really going on in LAUSD, and by extension, throughout the unionized public schools of California. Briefly stated, according to the teachers union, “justice,” inside and outside the classroom, is to implement a Leftist political agenda with no regard to the sentiments of teachers or parents.

Nakada’s assertion that “people don’t strike for 6 percent” is false, because getting a 6 percent raise was one of the goals of the strike, and they got that raise. How much will all of this cost? Well, if there are 30,000 teachers on strike, and their average salary is $75,000 per year, then a 6 percent raise is going to cost at least $135 million per year. We can expect this minimum amount, because whenever salaries are increased, the cost for other benefits such as pensions increase proportionately.

This concession of $135 million (or more) per year could have paid for the district to hire roughly 1,500 more teachers and support personnel, which when the details of the settlement are known, is likely to be roughly equivalent to how many new hires will be made. Where will the money come from? Who knows.

The more revealing phrase in Nakada’s article title is “we strike for justice.” What are examples of this “justice”? Would it include “restorative justice,” that well intentioned, benevolent sounding practice which in reality forbids schools from expelling students of any given ethnicity at a greater rate than expulsions occur within the entire student population?

Maybe “justice” is referring to “social justice,” which would include “protecting Dreamers,” “affordable healthcare,” “fair tax structures,” increasing the minimum wage, opposing the “privatization of public education,” immigrant rights, “green” space, bilingual education, reducing “inequality,” creating “racial justice” (such as through preferential scholarships for Asian, Latino, African, and LGBTQ students), and much, much more.

It’s unlikely that UTLA leadership would disavow these elements of their “justice” agenda. But is it nonpartisan? Is it focused on the skills that will truly enable a graduate to be successful – English literacy, math competency, and an awareness of history and civics that instills the American values of individual responsibility and hard work? Or is it a hard Left political agenda?

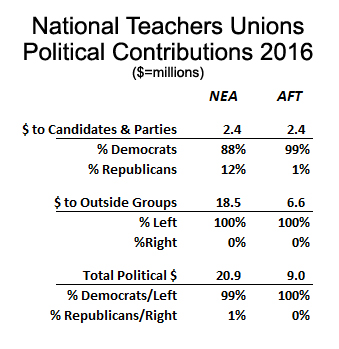

To answer that question, maybe the national political spending of the two largest teachers unions in America, the National Education Association (NEA) and the American Federation of Teachers (AFT) might be instructive. The table below, lifted from the book Standing Up to Goliath, written by the courageous Rebecca Friedrichs, reveals the political bias of these unions.

As can be seen, using 2016 data gathered by the Center for Responsive Politics, over 99 percent of direct political contributions by the NEA and AFT in that year were directed either to Left-leaning political action committees or to Democratic candidates and the Democratic party. Ninety-nine percent.

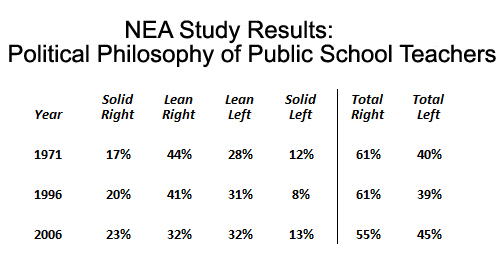

Can this degree of partisanship possibly be in synch with the sentiments of teachers who belong to these unions? Not according to the NEA’s own survey data on their members. As also reported by Friedrichs in Standing Up to Goliath, the most recent study available on this was a 2006 survey of American public school teachers, where they were classified as either “liberal,” “lean liberal,” “conservative,” or “lean conservative.” The data shows that 55 percent of public school teachers in the U.S. were either “conservative” or “lean conservative.” Has this changed over the intervening decade? Would the findings be different in California compared to the rest of the nation? While the answer to both questions is naturally yes, the question remains to what degree?

Two things can be reasonably inferred from these charts. (1) The political ideology of public school teachers in America is split roughly evenly between liberals and conservatives, and (2) the national political spending of the major teachers unions is almost 100 percent allocated to liberal causes and Democratic candidates. From their literature and their rhetoric, it is almost certainly accurate to state that the political agenda and political spending of the United Teachers of Los Angeles is in lockstep with that of these national teachers unions. It is also extremely unlikely that literally 100 percent of the UTLA teachers – and, more importantly, the parents of LAUSD students – adhere to an ideology that is 100 percent supportive of liberal causes and Democratic candidates.

Finally, the question of whether unions should even exist in the public sector is worth asking. The recent U.S. Supreme Court decision in the Janus vs. AFSCME case has recognized that all public sector union activity is inherently political. Therefore, why allow the California affiliate of the NEA, the California Teachers Association, to continue to collect and spend an estimated $325 million per year? Should the California affiliate of the AFT, the California Federation of Teachers, also continue to collect and spend an estimated $100 million per year?

Shall the UTLA continue to use their formidable power to deny school choice instead forcing students to attend mediocre and failing schools, to unionize charter schools despite many of them achieving spectacular results, to reject the common sense, bipartisan reforms proposed in the Vergara case, and to inculcate students with Leftist political ideology, at the same time as their financial demands leave the district teetering on the brink of insolvency?

By all recent indications, yes.

* * *

Edward Ring is a contributing editor for the California Policy Center.