Are Firefighters Hard to Recruit in California?

This article originally appeared in the California Globe.

In response to a recent California Policy Center analysis that provided an updated calculation of the average pay and benefits for full-time firefighters working for cities in California, one commenter claimed that it has become difficult to recruit firefighters. The accuracy of this claim carries significant implications. When employers can’t recruit employees, then to attract qualified applicants, they have to pay them more.

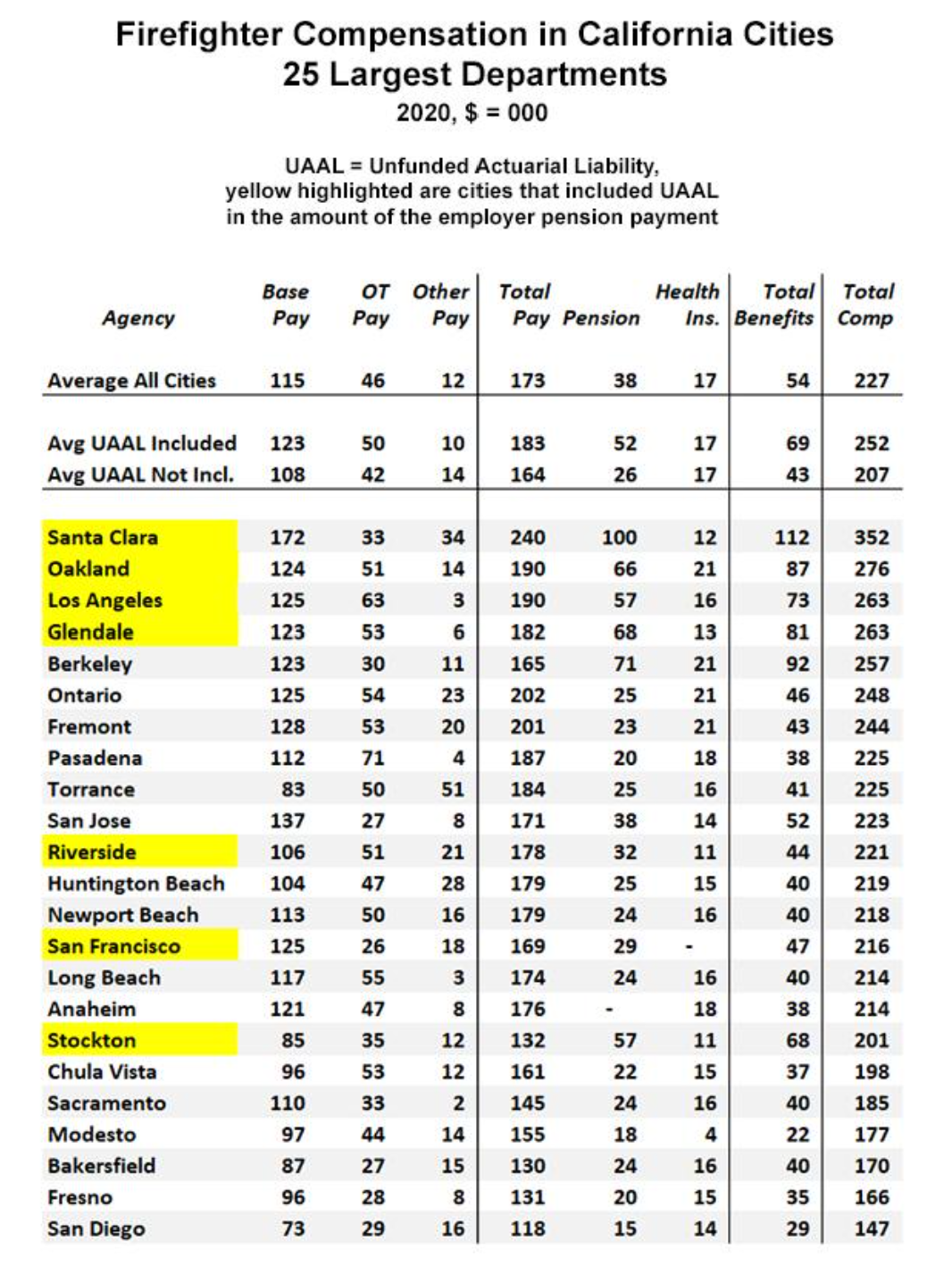

The findings of the analysis were unambiguous: The average full-time firefighter working for a California city is collecting a pay and benefits package that costs taxpayers over $250,000 per year. Moreover, firefighter recruitment has not been a challenge historically. With minimal advertising, cities used to receive hundreds of applications for every firefighter opening. If that has changed, what happened?

It turns out, a lot has changed. Firefighters, like all first responder positions where hazardous conditions are part of the job, get paid a premium. Over time, that premium has risen, not necessarily because the risks of the job have increased, but because the value our society places on human life and safety has increased. This means people who risk their lives must be paid more than they were in previous decades, and, concurrently, people who save lives as part of their job must be paid more because to meet the new and higher expectations, they have to bring more training and skill to their job.

Nonetheless, a pay and benefits package equal to a quarter million per year is a pile of money, even in California. And on average, the overtime component of that total only amounted to $42,000, which at time-and-a-half equates to 26 percent more hours. Given firefighters typically work (before accounting for overtime) 10 shifts per month, this means on average including overtime they’re working 12 or 13 shifts per month. But the biggest cost to employ firefighters is paying for their pensions, which on average costs California cities $52,000 per year per firefighter.

There’s a connection between overtime costs and pension costs. If pensions weren’t so expensive, cities could afford to hire more firefighters and pay less overtime. As it is, if pensions cost cities more than overtime, from an economic standpoint it makes sense to understaff the departments and pay the overtime. But is facing an extra few shifts each month the reason cities struggle to recruit firefighters? Isn’t it still a good job – work three four day shifts (or four three day shifts), and have the other 18 days off, every month, for a quarter million per year? That’s not a good enough proposition to attract recruits?

In some cases it is. A firefighter in a very wealthy suburban city may rarely have to actually fight dangerous fires or have to treat victims of gang violence. Their typical job will be responding to medical emergencies such as heart attack victims. These wealthy cities also can afford above average pay and benefits for their firefighters.

By contrast, firefighters that have to work in a high density, high crime area within a very large city are going to work a lot harder and take more risks. Their typical medical emergency is more likely to be a gunshot or stabbing victim, and the pace of their required responses may be relentless. And California’s very large cities often offer pay and benefits to their firefighters that are somewhat below average.

The City of San Diego is a stark example of this contrast in action. The total pay and benefits package for a full-time firefighter in the City of San Diego in 2020 was $147,000, significantly below average. Their pay was lower across the board: base pay of $73,000 vs an average of $115,000, and overtime of $29,000 vs an average of $42,000 (note that San Diego’s lower overtime pay does not equate to fewer overtime hours than the average). But the biggest difference was in the retirement benefit cost. San Diego, which has exchanged its defined benefit pension for a 401K plan, paid out $15,000 to pre-fund firefighter retirement benefits vs $52,000 on average.

Unsurprisingly, the City of San Diego is having difficulty recruiting firefighters.

There’s another wrinkle to this, however. It isn’t that San Diego can’t attract recruits to their fire academy. That’s only part of the problem. The bigger problem is that as soon as these recruits graduate from the academy and get hired and log a few years of on the job training, they leave. Why work for $147,000 per year when you can work for $250,000 per year?

The union’s solution to recruitment challenges is to raise pay and benefits. That’s always an option but where does it end? The story of unionized government in California is that whenever a bargaining unit got more for their members, every other bargaining unit became more underpaid by that same amount.

Here are some alternatives.

(1) Continue the work started by Gov. Jerry Brown with the PEPRA (Public Employee Pension Reform Act) reforms of 2013. Increase the solvency of California’s pension systems and lower the risk to taxpayers by attaching adjustments to pension benefits that are triggered when pension system solvency drops below healthy thresholds. When forced to do this back in 2013, the City of Detroit adopted what they termed “risk shifting levers,” which included, in order of application, and for as long as necessary, (1) no COLAs will be paid, (2) employee contributions will increase by 1% to 5% of base compensation, (3) most recently awarded COLAs will be rescinded, and (4) the benefit accrual rate will be decreased from 1.5% to 1%.

(2) Recognize that young applicants may attach more value to their base pay than to their eventual pension benefit, and recalibrate compensation packages accordingly. San Diego might consider this option. Increase the base pay instead of restructuring the retirement benefit and see what happens.

(3) Pay more for the tougher jobs and less for the easier ones. Firefighters working in South Central Los Angeles have more difficult jobs than firefighters working in Larkspur.

Ultimately, however, firefighters and their unions might consider the bigger challenges facing all Californians. The debate over what sort of premium a firefighter deserves for the risks they take is only half the issue. Why is the cost of living so prohibitive in California for everyone? What state and local policies could change to start to fix this problem?

If the firefighters union, and other public sector unions, supported candidates that are willing to spend tax revenues on practical infrastructure, and deregulate the extreme environmentalist inspired laws and mandates that hamstring California’s economy, the cost of basic necessities in California would drop. With economic and political uncertainty rising around the world, it is insane that California’s state legislature continues to enact policies that force Californians, now more than ever, to import food, lumber, fuel, other natural resources, and manufactured goods. Those products can and should be produced here in California in much greater abundance, driving down prices and creating more jobs.

There are political solutions to politically contrived scarcity. If those solutions were implemented, California’s firefighters, along with everyone else in the state, could live well for less money. To help do that, California’s powerful firefighters union will have to completely reassess their political priorities and the candidates they support.

***

Edward Ring is a contributing editor and senior fellow with the California Policy Center.