California’s Voters Approve New Taxes and Reject Tax Repeal

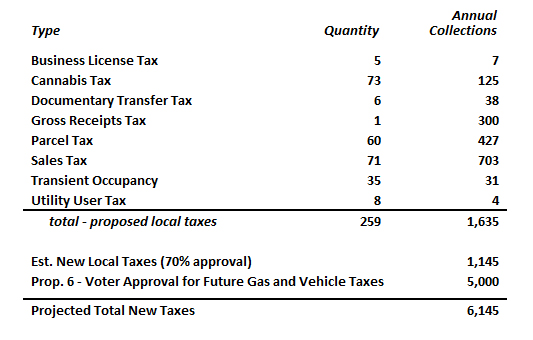

Although hundreds of election results remain to be decided across California, thanks to millions of vote-by-mail ballots still being counted, we can already project with reasonable accuracy the total amount voters approved in new taxes and borrowing. At the local level, new taxes nearly always are approved by voters. In 2016, out of 224 local tax proposals, voters approved 71 percent, adding $2.9 billion in new taxes. As shown on the table, if a similar percentage of November 6, 2018 local tax measures are approved by voters, California’s taxpayers will be providing local governments with another $1.6 billion per year.

Total Estimated New Annual Taxes Approved by California Voters

November 2018, $=Millions

While these new local taxes add billions – over time, tens of billions – of additional burden on California’s already beleaguered taxpayers, state ballot measures often offer even more significant tax increases. This November, voters turned down an opportunity, via Prop. 6, to eliminate an estimated five billion in new gasoline taxes. In all, California’s voters enabled another $6.1 billion in annual taxes, in a state that already has among the highest overall tax rates in the U.S.

California’s Total New Debt

The impact of new taxes is immediate. Rates go up, revenues increase, and government budgets swell. Compared to taxes, the impact of bonds is greater in the long run, but harder to recognize. In reality, bonds are just deferred taxes. From a financial perspective, it would almost be preferable to use taxes to fund many projects that currently rely on borrowing, because at least taxpayers would only be paying principal, and not interest. For example, if you assume 3 percent inflation, the present value of the payments on a $1.0 billion bond (5% interest, 30 year term) is $1.3 billion. That is, in real dollars, using a typical example, bond financing costs taxpayers 30 percent more than paying for services using operating funds. But the seduction of borrowing is hard to resist: big money today, while mortgaging tomorrow.

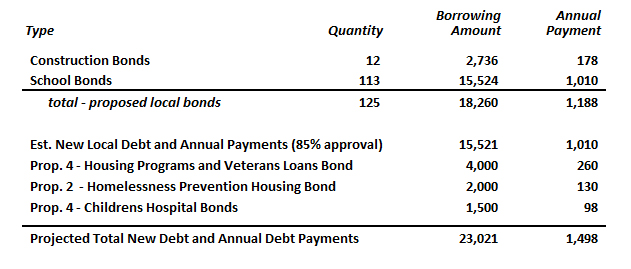

Total Estimated New Borrowing (incl. Annual Payments) Approved by California Voters

November 2018, $=Millions

As it is, this November, voters mortgaged a lot of tomorrows. And as always, the big money in the case of new bonds was almost all local. In 2016, of the 193 new local bond measures, voters approved a whopping 94 percent of them. This added $32 billion in new debt, equating to an estimated $2.1 billion in new annual principal and interest payments. As shown on the table, if a similar percentage of November 6, 2018 local bond measures are approved by voters, California’s taxpayers will owe another $15.5 billion. The principal and interest payments on this new debt will cost taxpayers another $1.0 billion per year.

At the statewide level, despite rejecting Prop. 1, the water bond, voters approved three new major state bond measures totaling $6.5 billion. Adding that to the likely $15.5 billion in local bonds, Californians this November will have added $23.0 billion in debt, costing $1.5 billion per year in annual payments of principal and interest.

California’s Total Accumulated Debt

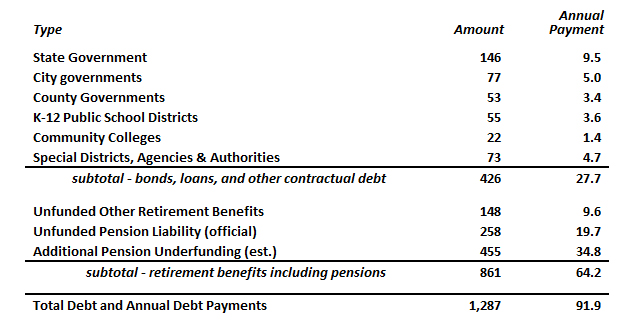

Who was it that said, “a billion here, and a billion there, and pretty soon we’re talking about serious money”? That would describe California’s total state and local government debt. When you look at what constitutes California’s total debt, accumulated over decades, it puts the relentless drive for higher taxes into context. The next table summarizes California’s total debt, as estimated by California Policy Center researchers Marc Joffe and William Fletcher in a 2017 study entitled “California’s Total State and Local Debt Totals $1.3 Trillion.”

Added in column two of this table is the estimated annual payments on this debt. As can be seen, the conventional debt – bonds, loans, and other contractual debt – paid back over 30 years at an interest rate of 5 percent, is costing California’s taxpayers $27.7 billion per year. Add to that, of course, annual payments of another $1.5 billion on new debt approved by voters earlier this week. But it’s in the unfunded liabilities for public employee retirement benefits where truly serious money burdens California’s taxpayers.

California’s Total Estimated State and Local Government Debt

2018, $=Billions

The story of how California’s taxpayers ended up on the hook for unfunded retirement pension liabilities easily in excess of a half-trillion dollars defies glib explanations. Anyone wanting to dig deep into California’s public sector pensions is encouraged to read the California Policy Center primer “Resources for Pension Reformers” and click on the many links for in-depth analyses of this complex topic. Simply put, an unfunded pension liability is the difference between the assets being managed by a pension fund at any time, and the present value of all promised future payments to retirees and active workers that have been earned up to that same point in time.

Over nearly three decades, some critical mistakes were made in California’s public employee pension fund management. Pension benefits were increased, again and again, by politicians eager to curry favor with public employee unions, but didn’t want to blow their current year budgets by granting salary concessions. Instead, they sweetened future pension benefits which did not incur significant immediate costs. Then the required annual costs to fund pensions were underestimated. Rates of return on invested pension fund assets were overestimated. Life expectancies were underestimated. And as the assets of California’s state and local pension systems began to fall well behind the value of their liabilities, creative accounting was employed to understate the amounts needed to reduce that debt.

Because of all these unknowns, there is a wide range of estimates of California’s total public sector pension debt. At the least it totals over a quarter trillion; at most, about triple that amount. This much is reasonably certain: if there is an economic downturn, and if pension benefits aren’t further reduced, it is likely that payments on pension debt will need to be in excess of $50 billion per year. In all, absent reforms and an epic continuation of the bull market, Californians are likely to be paying over $90 billion per year to service their state and local government debt. More than half of that will be to pay down unfunded pension liabilities.

The Public Sector’s Insatiable Desire for More Money

It is impossible to view California’s relentless pattern of tax increases apart from its public sector pension crisis, which is just beginning. Currently, the estimated annual payments on unfunded pension liabilities in California is estimated at $17 billion. Imagine the impact of that amount soaring to over $50 billion. And, of course, the taxpayer cost for pensions isn’t just to pay down the unfunded liability. The “normal cost,” that amount each year that has to be paid to fund the future pension benefits just earned in that year, is also rising. Based on modest adjustments to the assumptions governing projections of pension solvency, and based on official announcements already made by California’s largest pension fund, CalPERS, the normal costs for pension benefits plus the unfunded payments for pensions are estimated to rise from $31 billion in 2017 to $59 billion by 2024. No tax increase, anywhere so far, not even all of them added up, are sufficient to cover this shortfall.

If analysts find California’s looming pension funding crisis alarming, public employees who receive these pensions find it terrifying. That’s why, when a new local tax or bond measure is on the ballot, local governments use taxpayer funds to engage in “information campaigns” aimed at their voters that come very close to being political advocacy. Sometimes they cross that line. After such activities in support of a local sales tax increase in Los Angeles County, the California Fair Political Practices Commission found cause to charge the county, as well as the individual members of the Board of Supervisors, with 15 counts of campaign finance violations.

Californians had a chance to apply vigorous pressure to its elected officials by passing Prop. 6, which would have repealed the gasoline tax. That repeal would have cost state and local governments $5.0 billion per year. Why wouldn’t Californians seize an opportunity to lower what are the highest gas taxes in the U.S.? The answer reveals more about how far California’s public sector is willing to go in its desperate need for more revenue.

Earlier today and in the aftermath of the Nov. 6th election, Carl DeMaio, a former member of the San Diego City Council, who launched the Prop. 6 campaign, described the tactics of the opposition. California’s attorney general is responsible for reviewing ballot initiatives and approving the final wording of these initiatives as they appear on the ballot. According to DeMaio, rather than objectively describing the intent of Prop. 6, which was to repeal the new gasoline tax, the attorney general’s office used focus group research to compile a title and summary for the initiative that was worded in a manner more likely to get people to vote no. But it didn’t end there.

Not only is California’s attorney general alleged to have doctored the language of Prop. 6 to draw down voter support, California’s public sector unions spent millions on an opposition campaign. Overall, the opposition to Prop. 6 spent $50 million on their campaign, compared to only $2.6 million spent by its proponents.

Even in California, $50 million buys a lot of airtime. Lost on California voters, sadly, was the irony of a veteran firefighter who made $324,000 in 2017, serving as the main television spokesperson opposed to Prop. 6 which would have lowered taxes. California’s public sector unions collect and spend at least $800 million per year. They can, quite literally, spend as much as they need to spend to defeat candidates and propositions that do not favor their own interests.

Why don’t California’s voters and policymakers overcome high taxes and an unaffordable cost of living? Partly it’s due to the grip that public sector unions have on politicians, which prevents the state legislature from ever getting spending under control. Partly it’s the lack of any effective opposition, since the supposedly tax averse Republican party in California is a hollow shell, lacking on-the-ground infrastructure, strong candidates, or a shared and compelling political agenda. Saddest of all, it’s because the media in California is entirely unwilling to make the connection between public sector compensation, the power of public sector unions, and the punitive taxes and living costs that are its consequences.

* * *