Prairie Fire, 50 Years Later

Fifty years ago, in late July and August 1974, a 156-page paperback book with a red cover showed up in alternative bookstores, radical collectives, and coffee houses across America seemingly from nowhere. The book, Prairie Fire: The Politics of Revolutionary Anti-Imperialism, electrified and reinvigorated the nation’s dispirited and dispersing leftist radicals and exacerbated a new wave of political bombings and violence that lasted another four years.

Prairie Fire, a Marxian manifesto secretly published by the fugitive Weather Underground Organization (AKA “Weather” or “Weathermen”) in a cleverly disguised Boston brownstone, was a masterstroke of home-grown communist propaganda. The FBI, already beleaguered by congressional investigations for its illegal wiretaps and searches, was especially humiliated. After all, FBI agents had been scouring the nation for the Weathermen since 1970 and were no closer to an arrest in the summer of 1974 when the book appeared.

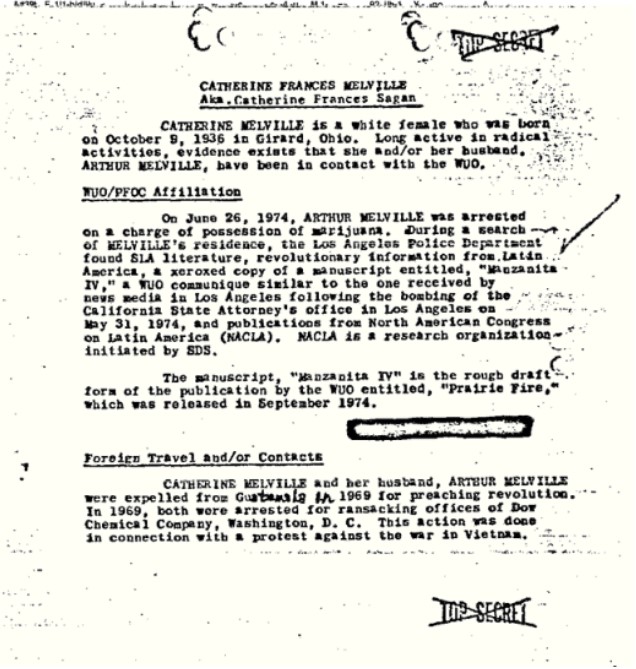

In fact, federal and local authorities had failed to thwart even a single Weatherman bombing (even with the illegal surveillance) or deal successfully with dozens of other violent groups inspired by Weatherman’s 1970 “declaration of war” on the United States. Even more embarrassing to the FBI is that they had a copy of Prairie Fire a month before secret couriers delivered 5,000 copies across the country. A draft manuscript was found by curious coincidence when Los Angeles police caught 41-year-old Arthur Melville with some pot on June 26, 1974.

The arrest seemed at first to be a lucky break for the LAPD, then involved in two manhunts. Melville was a former priest and Marxist with connections to west coast radicals; the FBI and the LAPD knew this. Acting quickly, police searched his home where he lived with his ex-nun wife Catherine, looking for evidence on the whereabouts of Patricia Hearst (who had joined her captors) and the remaining Symbionese Liberation Army (SLA) militants. A few weeks earlier, on May 17, six SLA militants were killed in a shootout with the LAPD in which no officers were hurt. The LAPD were also hunting for the Weather Underground. The Weathermen, annoyed that the SLA gunbattle was so one-sided, bombed the offices of the California Attorney General a few weeks after the shoot-out.

Neither the Melvilles nor their house revealed any clues. The LAPD found nothing to help them find Hearst or the Weathermen other than some SLA propaganda and a draft copy of a manifesto code-named, Manzanita IV, which the LAPD knew immediately was a Weather Underground product. Just after the attorney general’s office was bombed, Weathermen sent messages to the Los Angeles media claiming responsibility and included excerpts from Manzanita IV. The LAPD handed the manuscript over to the FBI, which did its usual head-scratching and little else. A month later, Prairie Fire was delivered nationwide.

Prairie Fire was both the Weather Underground’s magnum opus and their swan song. Two years later, all of Prairie Fire’s Weatherman writers were denounced as racists and counter-revolutionaries and were purged from the organization they invented. By 1977, they started surrendering to authorities.

As for the book itself, Prairie Fire stinks.

The book is a repetitive collection of cringey, communist tropes, bombastic calls for violence, and white loathing. Others, like Che Guevara, did it better and with more panache. There is no practical use for the book (nostalgia excepted) other than some classical homeschoolers have used it to teach the informal fallacies (for which it is a MASTERPIECE).

Even the grammar and syntax are awkward. One short section called, “The Sixties” starts:

“Denunciations of the struggles of the sixties as a failure do the enemy’s work. These surrenders are a live burial of our people’s great moments and weaken the future by poisoning the lessons of the past.”

The book reads like a three-legged chair, one can sit in it, but only with care and the irritating awareness that one is “sitting.” They should have recruited an editor to their cause.

Jonah Raskin, a former Weather Underground member, wrote in a 2019 Tablet retrospective on Prairie Fire:

“In hindsight, Prairie reads as the last testament of a small left-wing group that rioted in the streets of Chicago in 1969 during the Days of Rage, helped to destroy SDS (Students for a Democratic Society), and later reincarnated itself as a clandestine organization that placed bombs in government buildings, phoned in warnings, and issued communiqués sometimes only a paragraph or two, sometimes pages long.”

As a book, Prairie Fire is as inconsequential as a Fidel Castro speech or most TED talks.

So why bother remembering Prairie Fire at all?

Because its story is an American story, a story more about the decency of our nation than the aging radicals who wrote it. It is a story that demands we concede that the Americans who published Prairie Fire, and the FBI agents who hunted them, were dedicated but imperfect people afflicted by tumultuous times and their own impetuous or vengeful personalities. Their stories are packed with fascinating coincidences and ironies and remain exceptionally American; no other nation would tolerate or treat similar radicals and cops with such leniency post-bellum. In no other country would the criminals’ successes and the cops’ mistakes be so thoroughly and embarrassingly revealed. Cops and radicals undeniably committed crimes, tragedies, and injustices; innocent and not-so-innocent lives were needlessly lost while others had it coming. Civil rights were trampled and common decencies were ignored by radicals and authorities. Sometimes a truly bad guy got his, but not often enough.

It was an ugly year, 1974, yet another cultural nadir in that awful decade of nadirs. Prairie Fire reminds us of an America at a low ebb, beset by a sea of problems new to it and to the world, problems America bested with an odd combination of exhaustion and grace.

In fairness, any book written the way Prairie Fire was written would stink. According to Bryan Burrough in his 2015 book, Days of Rage, Weatherman Bill Ayers wrote the first draft. But the Weatherman central committee rejected it and went on to edit, redact, and re-edit for over a year. Quarrelsome people with feuding versions of communism (Mao vs. Stalin, Marx vs. Marcuse, etc.) are not a recipe for a concise manifesto.

The A-listers all got in on it: Bernadine Dohrn, Jeff Jones, Robert Roth, Celia Sojourn, and Ayers. Two others, Maoist Annie Stein (Jonah Raskin’s mother-in-law) and old-timey CPUSA leader Clayton Van Lydegraf, were also heavily involved. The two elders inevitably crossed hammers and sickles, leading to Lydegraf’s exile (he would have his revenge a few years later).

To the novice radical, Prairie Fire was electric. However, veteran radicals were shocked by a change in Weatherman ideology. After a perfunctory ten pages paying homage to themselves and the “violent struggles” of the 1960s, the authors wrote:

“We were wrong in failing to realize the possibility and strategic necessity of involving masses of people in anti-imperialist action and organization. We fixed our vision only on white people’s complicity with empire, with the silence in the face of escalating terror and blatant murder of Black revolutionaries. We let go of our identification with the people—the promise, the yearnings, the defeats.”

Maoist mass struggle had been loudly rejected as “too slow” by the proto-Weathermen in 1969 when they fought with the Progressive Labor (PL) faction for control of the Students for a Democratic Society (SDS). The original SDS was destroyed by the strife. The PL, as the Weathermen called them, believed in the old Marxist line that the working class was the key to revolution. The SDS radicals that later became the Weather Underground thought that only armed struggle would change things in a timely fashion. Now, in 1974, they had obviously changed their minds. The way forward, according to Prairie Fire, would be at the expense of both race struggle (mainly Black) and armed struggle.

Their intent is stated, in their muddled style, on page 24:

“Our final goal is the destruction of imperialism, the seizure of power, and the creation of socialism. Our strategy for this stage of the struggle is to organize the oppressed people of the imperial nation itself to join with the colonies in the attack on imperialism. This process of attacking and weakening imperialism involves the defeat of all kinds of national chauvinism and arrogance; this is a precondition to our fight for socialism.”

Fugitives living underground can’t very well organize the “oppressed” or defeat “arrogance” among the general population. The hard-core Weather fans, who were notably not living underground, were outraged at the relative moderation and change in strategy. Just as SDS broke apart in 1969, the radical youth movement began to break again in 1974.

Burrough writes in Days of Rage that the new verbiage was no innocent ideological shift, but part of a cynical and dishonest plan by the Weathermen to return to society as leaders of a united radical left. Silvia Baraldini, an early Prairie Fire adherent (who later joined the murderous May 19 Communist Organization), said in Burrough’s book:

“I read it, and I was skeptical, this glorification of white working-class stuff,” Baraldini recalls. “I was stupid. I fell for it. It wasn’t Weather, but it had that Weather mystique, and that was a powerful thing. We didn’t realize their leadership had already abandoned any pretense at being true revolutionaries and wanted only to surface and take control of the Left and enjoy the middle-class lives they had left behind. None of us knew how we were being manipulated.”

According to Arthur M. Eckstein’s history of the Weather Underground, Bad Moon Rising, an insulated and arrogant Weatherman cadre didn’t care what the dissenters thought and continued with their plan to transform themselves into a legitimate, above-ground organization called the Prairie Fire Organizing Committee (PFOC). PFOC, Weatherman by proxy, would indoctrinate new members against the armed struggle sermon they once preached. Eckstein writes:

“In fact, the very concept of armed struggle as Weather had waged it for the previous five years came under attack in winter 1975-1976 in the new Weatherman quarterly magazine Osawatomie. Weatherman had actually supported the cultish and grandiosely named Symbionese Liberation Army in early 1974, including the murder of Oakland school superintendent Marcus Foster and the kidnapping of Patty Hearst. Now they suddenly criticized the SLA… The leaders claimed it was a mistake to believe that ‘guerrilla struggle itself politicizes and activates the people.’ This was a stunning reversal of position.”

Stunning it was, especially since the name Prairie Fire came from Chinese communist leader Mao Zedong who said, “A single spark can set a prairie fire.” The “spark” being a small but violent act that incites a revolution.

Ironically, Prairie Fire itself was the spark that burned everything to ash. The Weather Underground plan failed spectacularly at the February 1976 Hard Times Conference on the University of Illinois’s Chicago campus. Hard Times, which was secretly planned to unite the radical left under Weatherman leadership, was ostensibly run by the PFOC, which denied a direct connection to the Weathermen. Over 2,000 delegates attended, representing scores of radical or racial groups. But the secret plans of the Weathermen were discovered, and the conference degenerated into a squalid morass of identity politics.

From Days of Rage, conference organizer Russel Neufeld said:

“I was almost lynched by a group of vegetarians because I hadn’t provided enough non-meat meals in the cafeteria… Every time something went wrong, I was constantly accused of being a racist.”

Clayton Van Lydegraf and his cabal marched into the chaos and began a series of interrogations. He eventually confronted his Prairie Fire nemesis Annie Stein and denounced her. The conference collapsed with a Stalinesque purge of the PFOC and the Lydegraf wing in charge.

Afterward, the Weathermen agreed to endure a series of Maoist self-criticism sessions. Bernardine Dohrn’s taped confession was especially cloying and pathetic. Channeling Winston Smith in Room 101, Dohrn confessed all and more, saying she engaged in “naked white supremacy, white superiority, and chauvinist arrogance.” She went on to blame Bill Ayers, her longtime lover, and Jeff Jones, an ex-lover, as fellow conspirators.

“Why did we do this? I don’t really know. We followed the classic path of white so-called revolutionaries who sold out the revolution.” (from Burroughs)

Lydegraf eventually made the Weathermen’s exile official, issuing a series of indictments accusing Weatherman of betraying the PFOC, abandoning the black cause, and trying to “destroy” gays, feminists, and lesbians.

The Weathermen limped back into hiding, now truly alone and still hunted.

Burrough writes:

“Dohrn’s statement reeked as much of fatigue and self-loathing as of surrender. But if her words arrived draped in melodrama and Marxist dogma, there was no denying their essential truth: The Weathermen had, in fact, sold out their dreams in return for their own personal safety.”

However dishonest the Weathermen were to their comrades in 1976, they were nevertheless being honest with themselves in late 1973. They were burned out, and they knew it. They were fugitives. They could not visit their families. Most of all, they feared that great devourer of the zealot’s soul: irrelevance.

And by 1974, events deepened that irrelevance. The Weathermen’s biggest bugbears were gone by the time Prairie Fire hit bookstores and the collective lairs: American troops had left Vietnam, the military draft had ended, college campuses were largely conquered by the left, Blacks had succeeded in asserting themselves in the media and were scoring political victories everywhere, and, only two weeks after Prairie Fire’s release, President Richard Nixon resigned. What else was there to do?

The Weathermen, all in their late twenties or early thirties and from mostly middle-class, white families, wanted lives beyond hiding from the FBI and setting off occasional, non-lethal bombs.

Therefore, the conspiracy to rule the radical left via the Prairie Fire Organizing Committee was an understandable gambit. If the fugitives were going to risk a public re-emergence, face arrest and jail time, they wanted to retain what remaining power and influence they had with radical masses who could, and would, raise funds and fuss on their behalf. So they gave it a go, and they lost.

After they were purged from the PFOC, the fugitives started calling lawyers and possible employers. They also started thinking about having families of their own.

In Zayd Ayers podcast, Mother Country Radicals, he asks his parents about this period. Bill and Bernardine tell their son how they decided to marry on New Year’s Eve, 1976.

Bill Ayers: We were on Cape Cod and we had a kind of a retreat of a few days. And it was around that time that we decided we were a couple.

Bernardine Dohrn: We’re not at a big New Year’s Eve party and we’re not in a crowd in the streets, but that’s when I think that it’s our anniversary. I still do to this day, you know? It was like, this is it.

Zayd Ayers Dohrn, narrating: They’d already been comrades for years—friends, partners—but now they’re deciding they want to build a real future together. My mom, as usual, takes the decisive step.

Bernardine Dohrn: I want to have a baby. Let’s have a baby.

Bill Ayers: Sure… (parentheses, what took you so long?)

(from transcript: https://crooked.com/podcast/chapter-8-hard-times/)

That Ayers and Dohrn could so freely vacation in Cape Cod is testimony to how little the FBI and the country cared about the Weathermen by 1976. They must have known none of their more violent (and hunted) Black or Puerto Rican brethren could ever enjoy the same privilege. Their decision to marry and have children was a tacit admission their war was over. It was also a repudiation of a Frankfurt School tenet the Weathermen once obeyed: that the traditional family was the beating heart of paternal capitalism and should be destroyed. They betrayed the revolution once more.

Actually, nearly all the most notorious Weather Underground women had children shortly after 1976: Dohrn, Wilkerson, Boudin, and Elenor Stein, who coupled with Jeff Jones. Zayd says the first pictures he saw of his mother are from this time:

“She’d been understandably camera shy as a fugitive, but she makes an exception during her pregnancy. In the snapshots. She’s out on the beach in San Francisco. Tan, wearing a bikini, sporting a big belly and short pixie-cut dyed red. She looks young and healthy. You can see why people call pregnant women glowing.”

From the same podcast, Bernardine describes Zayd’s birth:

Bernardine Dohrn: Then the midwife gets very serious. Where it’s like, Now, I’m setting you up. I’ll hold your shoulders up and you’re going to bear down. Then the sun was coming up. There’s this miraculous moment where they’re like, I can see the head, I can see the head. And then you feel like you can push more. And, you know, it was very long, but short of being very long, it was glorious and perfect and wonderful. And there you were.

A touching story and brutally ironic. Dohrn is infamous for her praise of Charles Manson at the 1969 Flint War Council where she said,

“First they killed those pigs, then they ate dinner in the same room with them, then they even shoved a fork into the pig Tate’s stomach! Wild!”

Sharon Tate was eight and a half months pregnant with a son when she was murdered.

Let there be no doubt Dohrn and Ayers, and all the Weather Underground, were a noxious strain of young Americans spewing malignant ideologies—the tenets of the Frankfurt School being one, their obedience to French philosopher Régis Debray (still living) is another. Their ideological loyalties led them to say and do callous things, such as including Sirhan Sirhan, Robert Kennedy’s killer, in Prairie Fire’s dedication. In 1969, Dohrn immediately grasped that the Tate-LaBianca murders were not random killings, but a strike against the American middle class to spark a race war. Charles Manson wanted to start the prairie fire from a single spark, too. Dohrn and company began to greet one another with a four-fingered fork hand sign (for the fork left in Sharon Tate’s pregnant belly) at the aforementioned Flint War Council.

Weatherman planned to bomb an Army dance at Fort Dix, also in 1970, which would have killed scores but instead killed three of their own in a Greenwich Village townhouse. (Ayers later claimed it was a “rogue” operation). Two Weatherwomen barely escaped with their lives, Cathy Wilkerson and Kathy Boudin. Boudin would later serve 23 years in prison for the killing of two police officers in 1981 and gave up her son, Chesa, to Bernardine and Bill. Chesa later became a San Francisco District Attorney and was the first DA ever to be removed from office.

Infamously, the Weather Underground leadership (namely, Dohrn) forced “smash monogamy” on their many collectives across the country. Smashing monogamy, they believed, would destroy the paternalistic system that oppressed women. Couples were broken apart, and intimacy was replaced with licentious sex. Weatherman Mark Rudd wrote in his memoir, Underground,

“Group sex, homosexuality, casual sexual hook-ups were all tried as we attempted to break out of the repression of the past into the revolutionary future.”

After 1970, Weather continued bombing, but because of the Greenwich Village debacle, they took pains not to kill anyone by planting bombs at odd hours and calling ahead to allow evacuations. None of their many bombings killed or hurt anyone thereafter. They also never carried guns. Still, they couldn’t be sure a bombing wouldn’t be lethal.

f their many sins, the Weather Underground’s least forgivable was its encouragement and goading of others to commit violence. Their 1970 “Declaration of War” inspired dozens of groups to attack anything associated with the military, industry, or government. In the declaration, Dohrn said,

“Tens of thousands have learned that protest and marches don’t do it. Revolutionary violence is the only way.”

One attack typical of the many Weather-inspired bombings was the 1970 bombing of the Army Mathematics Research Center in Madison, Wisconsin. The bombers, radical students unaffiliated with any known group, called themselves the “New Year’s Gang.” They adopted the name after they tried to drop bombs on an Army depot from a stolen airplane on New Year’s Eve, 1969. Fortunately, none of their bombs exploded.

They learned to make better bombs, though, and bigger ones. Their plan was to destroy the research center without hurting anyone. They assumed that if they set the bomb to explode in the early morning, no one would be inside. But, as is often the case with university students and faculty, there were people working overnight. One of them, physicist Robert Fassnacht, was killed by the huge ammonium nitrate and diesel bomb. Mortified and afraid, the bombers panicked and scattered; all but one was arrested. Fassnacht died, leaving a wife and child behind.

No robbery, bombing, or assassination seemed unworthy of Weatherman praise, deeds they could not stomach to do themselves. Prairie Fire salutes such ruthless killers as the Symbionese Liberation Army, the Black Liberation Army, and Puerto Rican nationalists. By the standards of these groups (and their evil twins in Europe, such as the Red Army Faction), the Weather Underground were wimps.

After Prairie Fire, these groups and others went on a four-year rampage. Of the 1,406 politically motivated bombs (which killed 164 people and injured 561) that exploded in the United States from 1970 to 1978, 565 of them exploded between 1974 and 1978.

Although the number of bombings had dropped off after 1971, their frequency increased again in 1973 and continued rising after Prairie Fire.

Bombings were daily news in 1975.

Kamala Harris’ Berkeley neighborhood was not spared. She was nine years old when the SLA kidnapped Patty Hearst two miles from her house on February 4, 1974. She probably never knew what happened. But she probably did hear the three bombs that exploded in 1975, which targeted the FBI’s Berkeley office, the offices of Pacific Gas and Electric, and Bank of America.

As the Weathermen planned their new family life and their return to conventional society, radicals ambushed police and bombed businesses, utilities, politicians, and monuments across America throughout 1974 to 1978 (and some kept going until 1981). President Ford was nearly assassinated… twice.

Did the Weathermen, in these maturing years, ever feel any shame about the violence and death they promoted? To this day, most have expressed none (some Weathermen have, such as Mark Rudd). That they have not openly expressed regret doesn’t mean that some pangs of shame or guilt, however fleeting, haven’t darkened some of their days. We can never know for sure.

The exiled Weathermen might have felt something like the character Rupert Cadell did in the 1958 Alfred Hitchcock movie, Rope. Cadell, played by Jimmy Stewart, is a Nietzschean prep-school headmaster whose cruel philosophy has driven two of his former students to murder. Horrified his proteges practiced what he preached, Cadell confronts Brandon and Phillip:

Brandon: Remember we said, “The lives of inferior beings are unimportant?” Remember we said—we’ve always said, you and I—that moral concepts of good and evil and right and wrong don’t hold for the intellectually superior. Remember, Rupert?

Rupert: Yes, I remember.

Brandon: That’s all we’ve done. That’s all Phillip and I have done. He and I have lived what you and I have talked. I knew you’d understand, because, don’t you see, you have to.

Rupert: Brandon—Brandon, till this very moment, this world and the people in it have always been dark and incomprehensible to me. I’ve tried to clear my way with logic and superior intellect. And you’ve thrown my own words right back in my face, Brandon. You were right, too. If nothing else, a man should stand by his words. But you’ve given my words a meaning that I never dreamed of! And you’ve tried to twist them into a cold, logical excuse for your ugly murder! Well, they never were that, Brandon, and you can’t make them that. There must have been something deep inside you from the very start that let you do this thing, but there’s always been something deep inside me that would never let me do it—and would never let me be a party to it.

Brandon: What do you mean?

Rupert: I mean that tonight you’ve made me ashamed of every concept I ever had of superior or inferior beings. But I thank you for that shame, because now I know that we are each of us a separate human being, Brandon, with the right to live and work and think as individuals, but with an obligation to the society we live in.

Rupert Cadell didn’t kill or become an accessory, but he was not blameless. His words were not twisted, just obeyed.

With new families to protect and the prospect of careers with sympathetic businesses and academies, most Weathermen quit.

Serendipity was with them; the moment was perfect. The country was in one of its periodic post-bellum moods—permissive, magnanimous, and generous.

Many of the charges against them had already been dropped because of FBI malfeasance. Most served little or no prison time or were merely fined. Bernardine Dohrn, once an FBI Most Wanted fugitive, spent only seven months in prison (and not for any Weather crimes, but for contempt). Even members of the New Year’s Gang had it easy: two served only three years in prison, and one did seven.

The nation’s jurisprudence was not reserved only for the white radicals. Black Panthers Bobby Seale and Eldridge Cleaver both received kindly treatment from U.S. courts despite their egregious crimes. Angela Davis, who gave a gun to a man who took over a California courtroom and killed the judge, was acquitted by an all-white jury. Bill Clinton later pardoned the seditious conspiracy of 16 Puerto Rican terrorists. He also pardoned Patricia Hearst.

Fifty years on, Prairie Fire and the fate of the Weather Underground should remind us all of America’s exceptional decency and fairness toward its most undeserving citizens. These were citizens who rejected the foundational virtues of classical liberalism and Christian forbearance and tried to destroy those virtues by fomenting a civil war. Those Weathermen who turned themselves in (Ayers, Rudd, Dohrn, Jones, Wilkerson, and others) benefited from the most magnanimous justice system in history.

What remains galling still today is that the Weathermen surrendered expecting that very fairness and magnanimity from institutions they had previously hated. Odd expectations from people who admired and visited Cuba, North Vietnam, and Warsaw Pact nations to train and plan. Dissidents like the Weathermen were (and still are) quickly disposed of by such nations. They deserved none of the fairness and generosity American institutions extended to them, yet they did have a right to receive such treatment—and they gladly accepted it: a staggeringly graceful endowment from a people and constitutional order they scorned (and likely still do).

America dealt with the Weathermen as it had dealt with other past enemies within and foreign by holding fast to Romans 12:20:

“Therefore if thine enemy hunger, feed him; if he thirst, give him drink: for in so doing thou shalt heap coals of fire on his head.”

To be sure, our apathy also allowed the radicals to fade into whatever their talents merited. But the coals they carried home must have given them at least a whiff of shame: But for the grace of God and a magnanimous people, you would be dead, Bernadine. Our nation has many vices, but vengeance is not one of them.

That is why we should remember Prairie Fire: it was not the Soviets or the Sandinistas, or Cuba or the Frankfurt School that heaped coals on the heads of the Weathermen, but their own countrymen—coals to light their own hearths and stop burning our prairie.

Article by Truman Angell

Author of the substack, The Anastomosing Dendrite

Sources are cited in the text. Melville source is below and

newspapers of the time.