Will California Voters Approve More Taxes and Borrowing?

If your city council puts a tax increase on the ballot, or your local school district puts a construction bond on the ballot, chances are very good it will get approved. Data from the past four November general elections is unambiguous. In November of 2020, for example, 80 percent of school bonds were approved by voters. Measured by dollar amounts, 91 percent of the proposed borrowing was approved. Similarly, voters in November 2020 approved 85 percent of local tax proposals; measured by projected tax receipts, 98 percent of the proposed tax increases were approved.

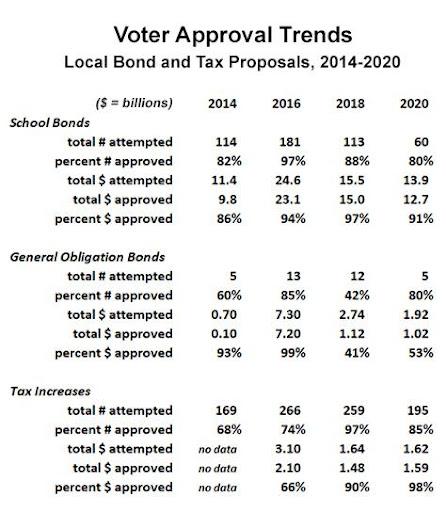

The following chart, using data provided by the California Tax Foundation, shows how billions upon billions of new taxes and borrowing have piled up over the past decade. And this chart is far from complete. It only reports on November elections, whereas additional hundreds of local tax and borrowing proposals have been approved by voters in primary elections and numerous special elections. Moreover, while the local bond totals are accurate, the projected total local tax revenues are far from accurate, because in about half of all cases, the data (ref. 2016, 2018, and 2020) for a new tax proposal does not report any estimate of how much additional annual revenue is anticipated.

Nonetheless the numbers are impressive. Over the past four November elections, voters have approved $60.6 billion in local school bonds, another $9.4 billion in general obligation bonds, and at least $5.2 billion in annual tax increases.

This is the context in which to evaluate what is being served up on the local ballots on June 7 in California. There are 11 school bonds attempting to get approval for a total of $967 million in new borrowing. There are two general obligation bond proposals that total another $419 million in new borrowing, and 27 proposals for new local taxes which will add an estimated $118 million per year to the tax burden of Californians. There is even one local tax repeal that made it onto the ballot via a local citizens initiative. Measure Z in San Bernardino, if passed, would repeal a parcel tax that proponents of the repeal allege was illegally extended countywide after one small community approved it in 2015.

How local tax and bond measures perform in the June primary could be a harbinger of shifting voter sentiment, or it may merely confirm the historical reality, which is that these proposals almost always pass. Back in March of 2020, for the first time in a generation, Californians did not approve the overwhelming majority of new tax and bond proposals that were put before them. Out of 125 proposed local bonds, only 31 percent passed; out of 111 proposed local tax increases, only 41 percent passed. But as we have seen, in November 2020 California’s electorate returned to form, with over 80 percent of the measures passing, representing over 90 percent of the money.

When it comes to gauging the sentiment of California’s electorate regarding taxes, proposals put forward on the statewide ballot are indicative, with somewhat encouraging recent data. In November 2020, voters rejected the split roll property tax, Proposition 15, despite proponents spending over $60 million.

Then again, with a supermajority in the state legislature, California’s Democrats don’t have to win the approval of voters to increase taxes, they just have to get the governor to sign their legislation. The only reason the split roll initiative went before voters in 2020 is because it was an attempt to countermand the property tax limitations of the legendary Proposition 13, passed by voters in 1978. A ballot initiative can only be overturned by voters, not by the state legislature.

The California Tax Foundation just released a report summarizing the many ways the state legislature intends to raise taxes. Notable among them is the latest version of a wealth tax, AB 2289, which would impose an annual 1 percent tax on the assets of current and former California residents with a net worth in excess of $50 million, rising to 1.5 percent on net worth in excess of $1.0 billion. If passed AB 2289 would raise an estimated $22.3 billion per year. It would tax items of fluctuating value, such as stocks, and even items of extremely subjective value, such as fine art.

If a wealth tax may invite too much opposition from the wealthy to ever pass, there is also AB 2802, a carbon tax “on entities that emit greenhouse gases in California.” Watch out for this one. Currently dormant, it has too much potential to go away. Everything emits greenhouse gas – expect not only oil refiners and heavy manufacturers to pay this tax, expect it to be assessed, for example, on homebuilders who don’t build high density housing. The carbon industrial complex is really just in its infancy. Expect a version of AB 2802 to eventually pass. Initial projections indicate it will cost taxpayers $5.0 billion per year. That’s just the tip of the iceberg.

Less ambitious tax proposals are also moving through the state legislature, but like the many local tax proposals, in aggregate they amount to additional billions that pass out of the hands of taxpayers and into the coffers of an insatiable government. There’s AB 1223, which would impose an annual tax on every firearm in private hands. There is AB 2836, that will stack even more fees onto annual vehicle registration. There’s even a proposal, thanks to the rather creepy AB 501, to impose fees on cremation. And, possibly worst of all, ACA 1, which would lower the vote threshold for voter approval of additional categories of local tax increases. As it is, most local tax proposals require a two-thirds majority to pass.

There’s a reason that every year we see additional dozens of state legislative proposals and additional hundreds of local tax proposals, even though most of them pass and taxes continue to climb. To quote from CalTax’s recent report: “The state budget for 2021-22 included $257.6 billion in total spending – a 13 percent increase from the prior year – and the governor’s proposed budget for 2022-23 calls for total spending to increase to $300.7 billion.”

A $300 billion state budget. This is a staggering increase. In 2014, eight years ago, the state budget was $152 billion. In today’s dollars that $152 billion is worth $184 billion. So during this eight year period when California’s population increased by a dismal 3.3 percent, the state government budget increased – in real dollars – by 64 percent.

How’s that working out for you? Maybe when it comes to good government, it isn’t the size of the budgets, but the success or failure of the policies that are costing all that money. This June, and again in November, California’s voters will have yet another opportunity to decide how they feel about those policies, and the tax proposals to pay for them.

***

Edward Ring is a contributing editor and senior fellow with the California Policy Center.